Background

Thought to have been formed in 1190 in the middle eastern territory of Acre, early evidence suggests the order started off as a benign operation - primarily responsible for hospitals and the protection of visiting catholic pilgrims. Within decades they had been expelled from the Middle East, and found themselves setting up shop first in Transylvania and then in Venice. Finding a permanent home was a tougher challenge though, and the Knights found themselves shunned by most rulers, roaming round searching for a more permanent base. Fortune smiled on them when Duke Konrad Mazowiecki invited the Knights to Poland, primarily to protect his territory from the Lithuanians to the east and the Prussians to the west.In 1230, and in conjunction with the Poles, the Teutonic Knights embarked on a crusade against the Prussians. So far so good, but in the long term the Knights would double cross the Poles; after decades of playing by the rulebook, this mercenary outfit was once more hired in 1308 by the Poles - this time to seize Gdańsk, a task they fulfilled with zealous enthusiasm, massacring the citizens who stood in their way. Known as ‘the Gdańsk Slaughter’, the Knights displayed a particularly worrying thirst for savagery, murdering anything up to 10,000 civilians (this figure is largely debatable, with many scholars suggesting Gdańsk didn’t even have a population of 10,000 at the time). The Pope was even moved to excommunicate the order, albeit for a short time.

As a PR stunt ‘the Gdańsk Slaughter’ really signalled the arrival of the Teutonic Knights as a force to be reckoned with. Unmoved by their open appetite for destruction, the Poles displayed a rather naive lack of common sense - and in a move they’d live to regret queried and dallied over the cash figure they were to pay the Knights. Not ones to sit around chewing the fat and talking numbers, the Knights did what evidently came so naturally to them - they launched into a full offensive against Poland. First Świecie fell, then Tczew.

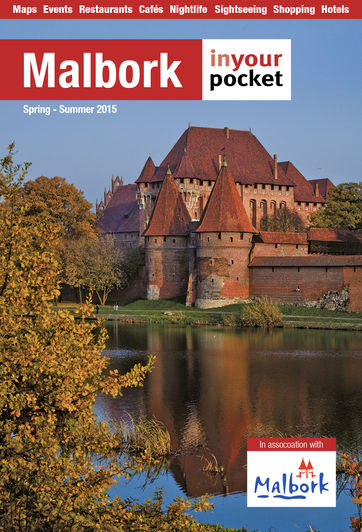

Malbork (Marienburg) Castle was established as their capital in 1309, and while they had made sworn enemies of both Poles and the Lithuanians, and aroused the disciplinary chagrin of the Vatican, the Knights looked a formidable mob. Northern Poland was theirs, and their control of the amber trade route and Hanseatic cities reaped them untold riches. After decades of sniping and fighting Poland was finally kowtowed into signing the 1343 Treaty of Kalisz, and an uneasy truce between the two powers ensued. For the Knights it signalled the height of their power - vast tracts of Northern Europe came under their control, and their Kingdom at one stage stretched from Słupsk to Estonia.

The first alarm bells were heard in 1386, a year in which Queen Jadwiga of Poland was married to Grand Duke Jogaila of Lithuania (who thereby became Władysław II Jagiełło, the new King of Poland). For the first time the Teutonic Knights faced a united enemy, though at first managed to duck the potential threat by playing Jogaila and his cousin Vytautas off against each other. The Teutonic empire was at its zenith, though much like Hitler’s over half a millennium on, would largely crumble with one epic battle.

The Battle of Grunwald

Fought on the 15th July, 1410, the Battle of Grunwald (known in some circles as the First Battle of Tannenberg - the Poles naming the battle after the place where the Knights were encamped and the Knights vice versa) was to become the defining engagement of Medieval times, and has been likened to Stalingrad in its impact and importance. Led by Władysław II Jagiełło and Vytautus the Great (now allies once more) a combined force of up to 50,000 Poles and Lithuanians faced off against 32,000 Teutonic Knights under the command of Grand Master Ulrich von Jungingen.The battle had been preceded by months of festering tension, and centuries of ill will between the two foes. In 1409 the residents of Teutonic-occupied Samogitia rose in rebellion against their masters, prompting both Poland and Lithuania to declare their intention to protect their borders if the Knights strayed where they shouldn’t having crushed the uprising. Ulrich von Jungingen was infuriated by such cocksure brevity, and on 14th August, 1409 declared war and mobilised his troops. Initial exchanges were conducted in the area around Bydgoszcz, and after a series of tit-for-tat battles an armistice was signed on the 24th June, 1410.

This was just a smokescreen, however; both Jagiełło and Vytautas had long been of the opinion that the Teutonic threat needed to be smashed once and for all, and the armistice allowed them to recruit more mercenaries and consolidate their strength. For their part the Teutonic Knights had a good idea what was coming, they just didn’t know where. Having anticipated a two-pronged pincer attack the Knights were caught with their trousers down when it dawned on them one very big, very nasty army was approaching - and making full steam in the direction of Marienburg.

Grand Master von Juningen moved fast to re-organise his troops, and on the 15th July 1410 the two forces came head to head between the villages of Grunwald, Stębark (a.k.a Tannenberg) and Łodwigowo.

That we know what happened next is to the credit of two people - Heinrich von Plauen the Elder, who wrote a series of heavily biased letters recounting the battle from the Teutonic side, and Jan Długosz, a priest, diplomat and something of an olden-days war correspondent. However their accounts, written from two opposite perspectives, offer several contradictions and a fair dose of medieval hyperbole. Precisely what happened has been lost to time, though needless to say historians have pieced together a good idea of the events that unfolded.

The battle appears to have kicked off at noon, and after hours of heavy fighting the Teutonic Knights appeared to be gaining the advantage. One source claims that von Juningen himself led his cavalry into the ranks of an elite Cracovian unit, and by all accounts the Polish-Lithuanian force were at this stage stretched to breaking point and bouncing off the ropes.

Using his last throw of the dice Jagiełło ordered his final batch of reserves into the fray, a move which proved a masterstroke. By this stage large numbers of Teutonic Knights had recklessly galloped off in pursuit of retreating Poles, and Jagiełło’s solar plexus blow stabilised a battle which was edging from his grasp.

The balance shifted once more when Nikolaus von Renys - founder of the Lizard Union, a group of Prussian nobles sympathetic to the Polish cause - decided to lower the banner he was carrying, causing his Teutonic soldiers to withdraw. The Knights would later behead von Renys for treachery and kill all his male descendents, while 500 years later the Nazis used this story of betrayal from within in their doctrine.

The battle was now Poland’s to lose, and von Jungingen once again rode into the thick of combat, leading from the front as he attempted to wrestle control from his Polish-Lithuanian counterparts. Regardless of their superior firepower (artillery is believed to have been used for the first time in this part of the world), the Knights’ forces were outnumbered. Pinned in from all sides they suffered devastating losses (including von Jungingen), and those who did escape encirclement were relentlessly pursued and cut down by light cavalry formations.

Aftermath

Over 8,000 Teutonic Knights are thought to have been killed, and over 14,000 captured. While Polish-Lithuanian casualties are perceived to be high (accurate figures appear to be unknown), Grunwald was seen as nothing less than a landslide success for their side. Jagiełło had triumphed over his bitter enemy, restored Polish pride and inflicted a hammer blow on an order which had seemed almost invincible. Strangely though, the decision to push on to Marienburg wasn’t taken until it was way too late.

Instead of going for the knockout blow the victors stayed on the battlefield for the next three days, no doubt raising a couple of glasses of mead, by which time the Teutonic Knights had rallied and organised the defence of their HQ. The Siege of Marienburg followed, but after a couple of months Jagiełło realised the futility of attacking an impenetrable monster like Marienburg and withdrew his troops.

But even the failure to capture Teutonic Ground Zero was not seen as calamitous. The Battle of Grunwald had decimated the enemy forces, and from then on their once-legendary army was patched and plugged with unreliable, mercenary troops. They had no choice but to sue for peace, and in 1411 the Treaty of Thorn (Toruń) was signed. The Poles proved sporting in victory, and somewhat surprisingly the Knights were allowed to maintain much of their Kingdom. Reparations demanded by Poland were also reasonable, though even as such they proved enough to bankrupt the Teutonic coffers.

The Knights, crippled by infighting, faded as a force, the Battle of Grunwald signalling the beginning of the end for a once unstoppable order.

Comments