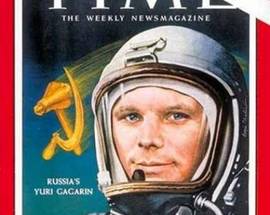

The son of peasants

It is popularly said that Gagarin was born the son of peasants. His parents did indeed work on a collective farm in the village of Klushino close to the town of Gzhatsk (now named Gagarin in his honour) in the Smolensk region. Despite their humble background they were both educated and his father was a skilled carpenter. As a youth Gagarin left home to do an apprenticeship in an ironworks. Whilst there he was selected for further training and was invited to study at the Saratov technical college. As a hobby in Saratov he joined the aeroclub and learnt how to fly light aircraft. When he left the technical school he enrolled at the Orenburg Pilot’s school just as the Soviet Union began to accelerate its work on its groundbreaking space programme.Soviet space dogs

As the cold war reached freezing point, the USA and the Soviet Union entered the space race both hoping to be the first nations to conquer space. In 1957 the Soviets, led by the extraordinarily talented rocket scientist Korolyev, launched the first manmade satellite (sputnik) into orbit. This was soon followed by the first animal in orbit, Laika the dog. Laika sadly never returned to earth but in 1960 the heroic dogs Belka and Strelka successfully orbited the earth for a day and returned safely, laying the final grounds for the first human space flight.From 2,000 to 1

Over 2,000 Russian military pilots were considered for the first human space flight. Only 200 of these made it through to the next round of testing and of them only 20 were selected for intensive training. After passing through rigorous physical and psychological testing two men remained as candidates to fly in Vostok 1 - Yuri Gagarin and Gherman Titov. In the end Gagarin was chosen due to his small stature (5 foot 2, perfect for the tiny Vostok capsule) and due to his mental stability and political clout as the son of peasants (Titov on the other hand was the son of teachers).Titov didn’t miss out though and was the second man to orbit the earth in the Vostok 2. Titov also holds his own firsts as the first human to sleep in space and the first to experience ‘space sickness’ (a form of motion sickness experienced by about half of all astronauts/cosmonauts).

Let’s go!

After 11 months of intensive training and years of work on perfecting the Vostok rocket, the Soviets were ready for blast off. Based at the Baikonor cosmodrome in Kazakhstan, Gagarin was reportedly meticulously prepared and ready to fly and settled in for a sound night’s sleep, - unlike the rest of mission control who spent the night nervously pacing. When asked how he could sleep so easily given his historic flight the next day, Gagarin apparently responded “Would it be right to take off if I were not rested? It was my duty to sleep so I slept." On the day of the flight Gagarin smilingly entered the Vostok capsule and was strapped in. Whistling the popular patriotic tune by Shostakovich The Motherland Hears, The Motherland Knows, Gagarin prepared for lift off, and as he was launched into outer space was heard by mission control shouting “poekhali!” Let’s go!‘I can see it – so beautiful!’

Gagarin’s space flight lasted 108 minutes (enough time to orbit the earth once) and he reached an orbital speed of 27,400 kms per hour. In his first message to mission control and as the first man to communicate with earth from space, Gagarin pondered on the beauty of it all exclaiming “The Earth is blue [...] How wonderful. It is amazing.” The quote that “I can see no God from here” which has been credited to Gagarin, actually came from the atheist Khrushchev who said during an anti-religious Soviet party conference; “When Gagarin went to space, he saw no God on this earth”.‘I am a friend, comrades, a friend.’

Gagarin had been given only a 50% chance of surviving his trip up to space and the odds on him returning safely were even less favourable. In order for Gagarin’s space flight to be officially named a world record, he was required to stay in his capsule all the way to the earth. However, upon re-entering the earth’s atmosphere he encountered serious technical problems, that would have meant certain death if he hadn’t ejected himself from the capsule.In order for the flight to be officially recognised by the international aviation authority the Soviet’s were forced to keep the real details of the landing a secret and the story of Gagarin’s curious return to earth were only made public some years later. At some 7,000 metres above the earth, after losing contact with mission control Gagarin evacuated himself from the capsule and free-fell through the air for several kilometres, before opening his parachute and floating down to the ground. Protected by his space suit he was able to withstand the air temperatures of nearly -30 degrees.

Landing in the middle of the Kazakh steppe, the first people to greet the first man in space were an obviously confused local babushka and her granddaughter. An elated Gagarin is reported to have greeted the bewildered onlookers by telling them “I am a friend, comrades, a friend!”

A hero’s welcome

Back in Moscow Gagarin was honoured with a six hour long parade on Red Square before embarking on a trip around the world to talk about the wonders of space travel, bringing with him his famous dashing smile and passion for the beauty of the earth. Speaking about what the earth looked like from space, he said "What beauty. I saw clouds and their light shadows on the distant dear earth... I enjoyed the rich color spectrum of the earth. It is surrounded by a light blue halo that gradually darkens, becoming turquoise, dark blue, violet, and finally coal black."Gagarin travelled to Britain, Japan, Germany, Finland, Italy, Canada and all across the Soviet Union spreading a message of peace, unity and environmentalism, inspired by having seen the earth from above. “Circling the earth in the orbital spaceship I marvelled at the beauty of our planet. People of the world!! Let us safeguard and enhance this beauty - not destroy it".

Life after space

Soon Gagarin became one of the most popular and best loved public figures in the Soviet Union. Due to his high profile many became afraid of what would happen were he to travel to space again and die. This is why his first flight to space was also his last. Over the next few years the Soviet authorities tried to prevent him from taking part in further space flights and Gagarin was forced to compromise and became the head of the cosmonaut’s training centre at Zvezdnoy Gorodok (Star City) just outside Moscow.During this time Gagarin also began to re-train as a fighter pilot and in 1968 at the age of just 34 he was killed in a fatal training flight around 100kms outside of Moscow. His cremated remains were scattered next to the Kremlin walls in Moscow and his office in Star City was turned into a museum and shrine to the first man in space. Now 50 years on Gagarin has a town, launch pad, moon crater, ice-hockey cup, planetarium, airliner, asteroid and holiday – (Cosmonaut’s Day - colloquially known as Yuri’s night and celebrated on April 12) all named after him.

Did you know: Cosmonaut's superstitions

Russians are generally a superstitious lot and with the mortality rate in the space industry at something like 3%, Russian cosmonauts are even more superstitious than usual. Here are just some of the obligatory rituals of a cosmonaut pre- and post- space flight.The pre-flight rituals start at Zvezdnoy gorodok (Star City) where the cosmonauts train together before flying. All the cosmonauts head to Moscow’s red Square to leave red carnations at the place by the Kremlin walls where Gagarin’s ashes and the ashes of other cosmonauts who have died during space missions are buried. Then they visit Yuri Gagarin’s office in Star City, which has been preserved as a shrine to the first cosmonaut and sign Gagarin’s guestbook, before heading off to the cosmodrome in Kazhakhstan.

On arrival at Baikonur cosmodrome the cosmonauts stay at the Hotel Cosmonaut and spend the next two days following various rituals. One of the most important is that they do not observe the rockets being transported out to the launch pads. Instead cosmonauts usually get their haircut during this time. On the day before the flight the cosmonauts are blessed by an Orthodox priest and then invited to watch the 1969 Soviet film White Sun of the Desert in the hotel. Attendance at the screening is compulsory.

On the day of the launch, the cosmonauts are treated to a glass of champagne at breakfast and then before collecting their last things from their rooms they sign the hotel room’s door. Back down in the lobby they are sent off to the buses with the Soviet rock song The Green Grass Near My Home by the Russian band Zemylane (the Earthlings). On board the bus (suitably decked out with plenty of lucky horseshoes) half way across the airfield, the cosmonauts are invited to take part in the most notorious cosmonaut superstition.

According to space folklore, when Gagarin was being bussed out to the launch pad, he requested that the bus be stopped so that he could go to the toilet one last time. As they were in the middle of a giant airfield he had no choice but to urinate against one of the wheels of the bus (the right rear wheel so legend has it). Ever since then almost every cosmonaut at Baikonur has repeated the ritual, with some enthusiastic female cosmonauts taking part by bringing their own pots of urine to sprinkle on the bus.

If the mission is heading to the International Space Station Russian crews like to keep up with ancient Russian traditions by offering their crew members at the space station a welcoming gift of bread and salt. After the decent to earth the cosmonauts enthusiastically sign the inside of the burnt-out landing capsule and also the inside of the transfer helicopter. Every successful cosmonaut plants a tree in front of the Hotel Cosmonaut in Baikonur and once safely back at Star City the crew visit Yuri Gagarin’s memorial to remember once again the great space pioneer.

Find out more:

Moscow's cosmonautics museum

To see and find out more about Yuri Gagarin and the Soviet space race, be sure to visit Moscow's excellent Cosmonautics museum where the stuffed bodies of Belka and Strelka are on display as well as original space suits, part of the Mir space station and much much more. Above the museum you can also admire the alley of the stars which features busts of all the most important men and women involved in the Soviet space programme.

Comments