‘Major’ Fydrych and the Orange Alternative

Born April 8th, 1953 in the northern city of Toruń, Waldemar Fydrych moved to Wrocław to study history and art history at Wrocław University, where he began what would become a lifelong involvement in politics, joining the protests and strikes that were breaking out across Poland in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, including travelling to protests at the Gdańsk Shipyards. At the University he created a branch of the Independent Students Union and founded the New Culture Movement, launching a subversive newspaper in which he published “The Manifesto of Social Surrealism” in March 1981 - a document that spelled out the ideology of what would later come to be known as the Orange Alternative protest movement. In April 1981 Fydrych co-organised a massive peace rally in Wrocław, putting himself at the fore of the local protest movement.

Known to his friends and followers as 'The Major,' far from having any inclination towards the military, Fydrych’s ironic moniker actually stems from an incident where he feigned insanity to avoid national service. Called up for military duty, Fydrych appeared in front of an army panel dressed in the regalia of a major, addressing himself as such, and calling his superiors colonels while insisting that they enlist him. His narcissistic, disrespectful and deranged enthusiasm had the desired effect of leaving the army commission in no doubt that he was as mad as a March hare, and in no way fit to serve in the Polish military. Tasting his first success with subversive absurdity, the nickname stuck and the Major made it his basic credo going forward to fight the establishment with an overt silliness and surreality that would make the authorities look the bigger fools if they tried to repress it.

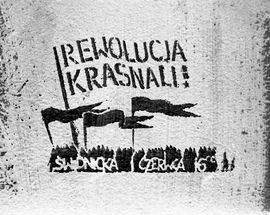

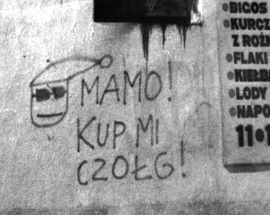

As “actions of protest became a norm of life” and the political atmosphere across Poland became more unstable - teetering “at the edge of an abyss” in the words of General Jaruzelski, leader of PL’s communist government - martial law was declared in December of 1981. Civil liberties were drastically restricted, independent assembly and political organisations were outlawed, university and school activities were suspended, censorship and a curfew were imposed, and political demonstrations were met with military force. Out of this threatening atmosphere came the genesis of the gnome as ironic political dissident. With the militia roaming the streets, anti-establishment graffiti was painted over with such frequency and diligence that seemingly every public space was white-washed with crude splotches of paint. Armed with paint cans of their own, Fydrych and his merry pranksters would then go out and quickly paint over the fresh patches of paint again - not with political slogans, but with gnomes.

The gnomes illustrated the regime’s fruitless attempts to censor public space, while poking fun at the militiamen who went around like fairies magically making anti-government graffiti disappear overnight. But more than anything it humiliated the authorities who were then (in their estimation) forced to go around the city painting over/censoring innocuous images of little gnomes; to the outside world it not only looked ridiculous, but pathetic - as did arresting someone for painting a picture of a gnome. By choosing an icon with no political connotation, Fydrych had created a brilliant political device. As the cheeky ploy gained popularity, gnomes soon began appearing in other cities as well. Detained in a Łódź police station for graffiti, Major Fydrych was happy to esoterically explain the gnomes to state authorities: “The thesis is the anti-regime slogan. The anti-thesis is the splotch of paint. And the synthesis is the gnome.”

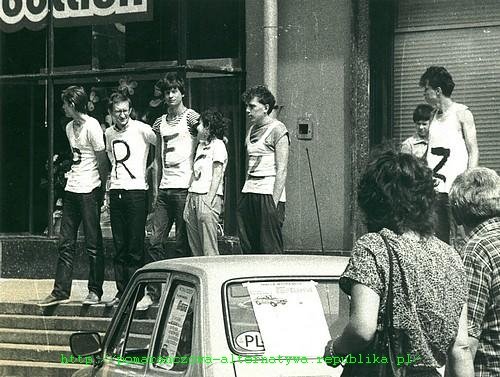

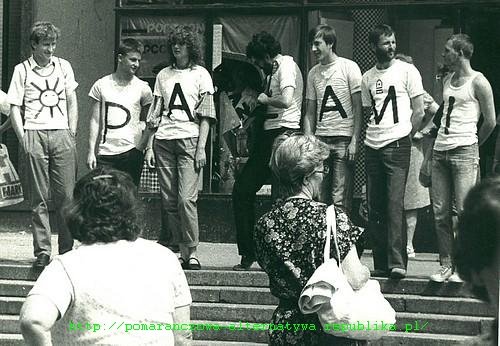

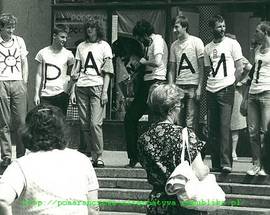

Beginning in 1986 Fydrych initiated a series of increasingly bizarre happenings that would indeed 'synthesise' themselves into what became known as the Orange Alternative movement. Having learnt from the bloody protests of the early '80s, Fydrych sought to avoid aggressive confrontation with the militia by staging a series of demonstrations that were so silly armed intervention would seem ludicrous. One such action included thirteen protesters with individual letters printed on their t-shirts. Lined up together they announced "Precz z upałami" (Away with the heat), though whenever the police would turn their backs the chap wearing the letter ‘u’ would slip from view and the message changed to "Precz z pałami" (Away with the truncheons).

|

|

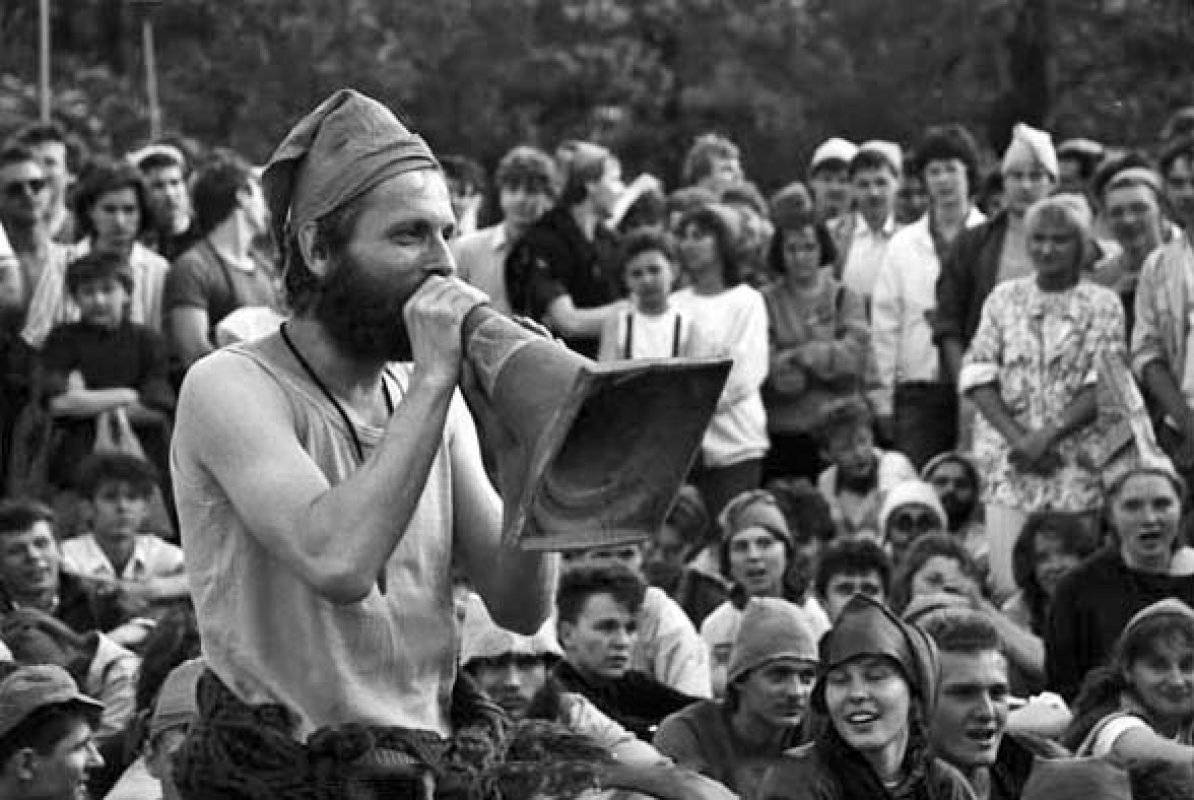

Handing out iconic peaked orange gnome hats to passing pedestrians, Major lead nonsensical marches for gnomes’ rights. The resulting arrests of orange-clad ‘gnomes,’ plus dozens of bystanders also detained for wearing orange, often made the nightly news and succeeded in making the authorities look idiotic. One parade saw 2,000 people march through Wrocław dressed as Father Christmas, their placards calling for the release of Santa Claus. Mass arrests followed, and in the confusion several store workers legitimately dressed as Santa were rounded up and thrown in the cells. For the anniversary of Russia’s October Revolution Fydrych urged his cohorts to turn up with anything red: "Wear red shoes, borrow a red bag from your neighbour, paint your fingernails red, buy a bread stick with ketchup." Once more the authorities clamped down on the illegal gathering, with farcical scenes ensuing. The protest hit international television, where it served to make a mockery of the communist system.

Fydrych himself was arrested on innumerable occasions. He was once jailed for handing out tampons to women, though the general uproar that followed saw him released by the red-faced authorities after three months. As the Orange Alternative grew, more and more people began participating in absurd happenings all over Poland; 4,000 agitators took to the streets of the capital chanting “We love Lenin!” while 10,000 participated in a ‘Gnome Revolution’ event in Wrocław.

Although it had no direct links with the Solidarity movement, the two were connected with a common cause - that of breaking the system, and Solidarity organisers supported the Orange Alternative by printing leaflets and posters and promoting Orange actions. Though the Solidarity movement gets the lion’s share of the acclaim for bringing down the communist regime in PL, the Orange Alternative’s role in its eventual success should not be understated. Behind their smokescreen of absurdities the Orange Alternative actually assumed a prominent role in the anti-totalitarian protests of the 1980s, helping bring Poland’s plight to international attention through their zany happenings. Fydrych’s campaign for freedom of speech was recognised across the world, and in 1988 he was given the Solidarity Award from London's Puls Publications, and the Polkul Award from the Polish community in Australia.

Photo: Agnieszka Couderq. (c)orangealternativemuseum.pl

After the communist regime finally kicked the bucket in 1989, the Major sought a new life in France, working for several years as a painter and decorator and continuing to involve himself in anarchic happenings. Returning to Poland in 2001, he jumped back into the political arena by founding the ‘Dimwits and Dwarves’ party (Gamonie i krasnoludki) and running for Mayor of Warsaw in the 2002, 2006 and 2010 elections under the campaign slogan “When you vote for a dimwit, you vote for yourself.” Though he garnered only 0.41% of the vote in 2006, he got more votes than the leader of the governing coalition party LPR - a fact the local media was quick to celebrate.

The Orange Alternative also played a role in Ukraine’s Orange Revolution of 2004, with Fydrych and other supporters of the revolution travelling from Warsaw to Kiev in an orange battle bus, where, before a crowd of thousands, they presented President Yushchenko with a fifteen metre orange scarf symbolising Polish-Ukrainian solidarity. In 2005 Fydrych and the OA were honoured with an exhibition in the Brussels European Parliament, and in 2012 the Major earned himself a Ph.D. in Fine Arts from the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw. Today he spends much of his time in the capital no doubt inspiring those around him to be creatively subversive and subversively creative at every opportunity.

Wrocław, City of Gnomes

Thanks to the Orange Alternative, gnomes are inextricably linked with Wrocław, and in a somewhat ironic twist, what began as an act of vandalism has developed into an official icon of the city. In 2001 city officials decided to honour the legacy of the Orange Alternative by placing a gnome statuette at the corner of ul. Świdnicka and ul. Kazimierza Wielkiego, where Orange Alternative demonstrations often took place. Standing atop a strange pedestal that resembles a large toe, Papa Krasnal is the largest of his progeny and proved so popular that in 2005 the city commissioned local artist Tomasz Moczek - a graduate of the Wrocław Academy of Fine Arts – to create more gnomes. Envious local businesses quickly got in on the game by contracting other local artists to produce more, and in almost no time at all gnomes had proliferated around Wrocław to the point that they now constitute a veritable ‘sub-population’ of the city. The little devils are currently rumoured to be running rampant to the score of over 400(!), making it literally impossible for visitors to try to find all of them in one visit. Seeing how many gnomes you can spot while you're in Wrocław, however, is an incredibly fun alternative to traditional sightseeing, and a great way to keep the kids involved while tramping around town. Happy hunting!

More Info

orangealternativemuseum.plkrasnale.pl

Comments