Wrocław, believe it or not, had a total of eleven (eleven!) native-born Nobel laureates in the 20th century, beginning with Thomas Mommsen’s prize for literature in 1902 and spanning Richard Selten’s 1992 prize for his work in game theory. While all of Wrocław's Nobel nerds are arguably worthy of in-depth investigation, perhaps none of their stories are as sensational, complex and significant as that of German chemist Fritz Haber (1868-1934), one of the most important scientists in human history.

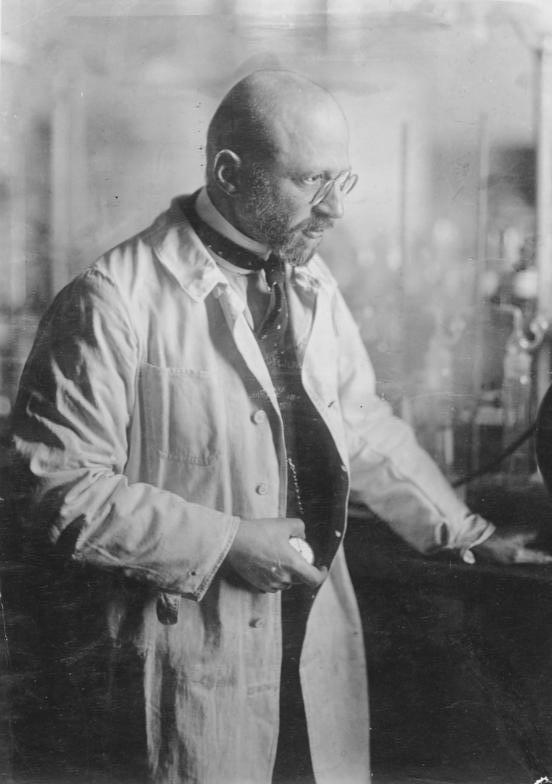

Most remembered for his invention of a process for synthesising ammonia – a feat which earned him the 1918 Nobel Prize in Chemistry – Fritz Haber's legacy is as complex as was his work in the lab, which yielded world-altering results. In creating the means for producing synthetic ammonia, Haber unlocked the large-scale production of both life-nourishing fertilisers and destructive explosives. This dichotomy of beneficial and detrimental, good and bad, and ultimately life and death, would repeat itself throughout the drama of Haber's own life, and afterwards, creating quite a thorny legacy. More than just another bespectacled lab scientist whose brilliant invention could have dangerous applications, Haber was a fanatical brinksman and nationalist, who dedicated himself to the German war effort, even personally overseeing the use of poison gas on WWI battlefields. [Ironically, he also had Jewish roots, and his work on chemical warfare would later be applied in Nazi extermination camps, with tragic consequences for his own family.] At the same time, he immediately improved agricultural production across the globe, and it is estimated that today over half of the world's entire population is nourished with food that wouldn't exist without his process for synthesising ammonia. Read on, and you'll learn that his work had as profound an impact on his personal life as it did the world, sustaining and scorching both.

Early Life & Career

during her studies at University of Breslau.

Passing his high school exams in Breslau/Wrocław, Fritz began an apprenticeship at his father's company, swiftly became intrigued by the consequences of combining various chemicals, and soon left to study chemistry in Berlin, then Heidelberg, then back to Berlin, where he earned his PhD. Using his father's connections, he flitted between apprenticeships and the family business, but clashed too often with his father to sustain the latter, eventually taking teaching positions at the University of Jena (where it should be noted he converted to Protestantism) and finally a full professorship at the University of Karlsruhe. It was in Karlsruhe that Haber's name began to receive recognition, and then renown, as he collaborated with other top German minds and authored several books based on his research of dyes and textiles, electrochemistry, chemical thermodynamics, free radicals and other concepts we won't feign to comprehend.

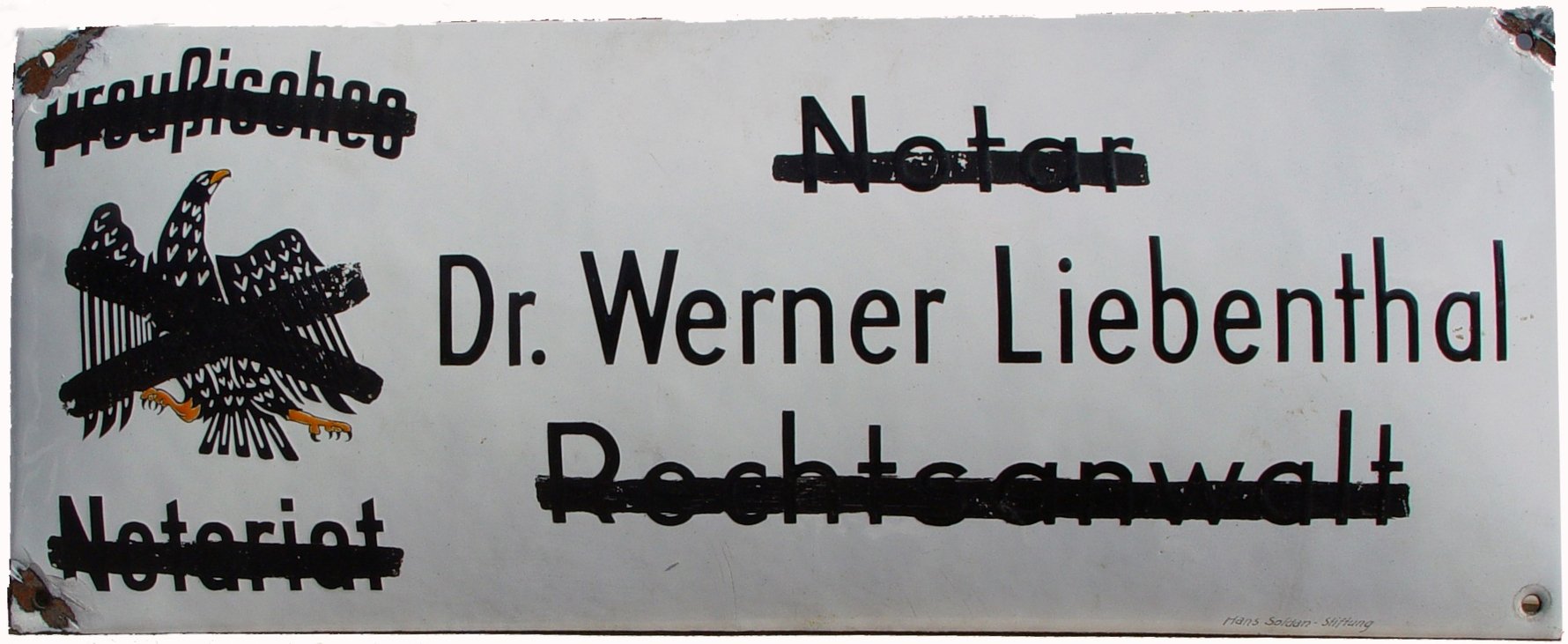

Although shunned by his father, Haber found a companion in fellow genius, chemist and Breslauer, Clara Immerwahr - a brilliant scientist in her own right, and the first woman in Germany to earn a doctorate degree (in Chemistry, from the University of Breslau). A strong pacifist and women's rights advocate, Immerwahr refused Haber's marriage proposals in favour of her own independence, career and research for over a decade before finally marrying him in 1901 at age 31. A year later, their only child, Hermann, was born.

Birdshit Crazy Science: Ending the 'Guano Age'

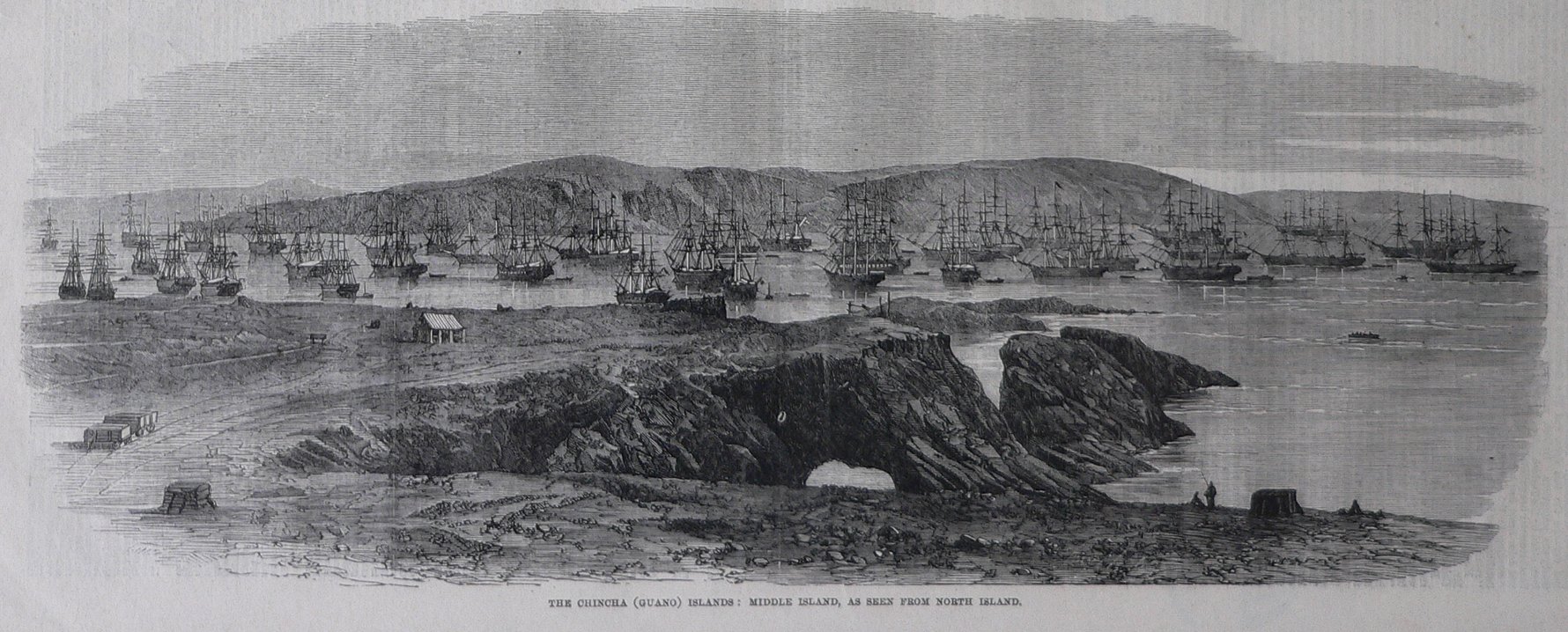

All the while, the world had a problem. Its natural resource for ammonia and nitrogenous compounds – necessary to the production of fertilisers and thereby food – was not large enough to meet rising global population numbers and increasing worldwide demand. In 1802, Prussian explorer Alexander von Humboldt had discovered these coveted properties in massive guano deposits - that is, enormous piles of bird excrement - off the western coast of South America and sparked the 'Guano Age': 100 years of mining, harvesting, pirating and imperialism all centred around the world's bird and bat poo supply. From 1865-1883, multiple full-fledged wars (dubbed names like the 'Guano War,' 'Saltpetre War' or 'Nitrate War') were even fought between Spain, Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador and Chile over their claims to coastal guano deposits. If you're not sure who eventually came out on top in those conflicts, just look at a map of South America (it was Chile). We shit you not, much of 19th-century economics, exploration, colonialism, imperialism and island landgrabbing (including much by the United States) was all predicated by a desire to acquire massive quantities of nitrate-rich bird droppings (kinda like oil in the 20th century).

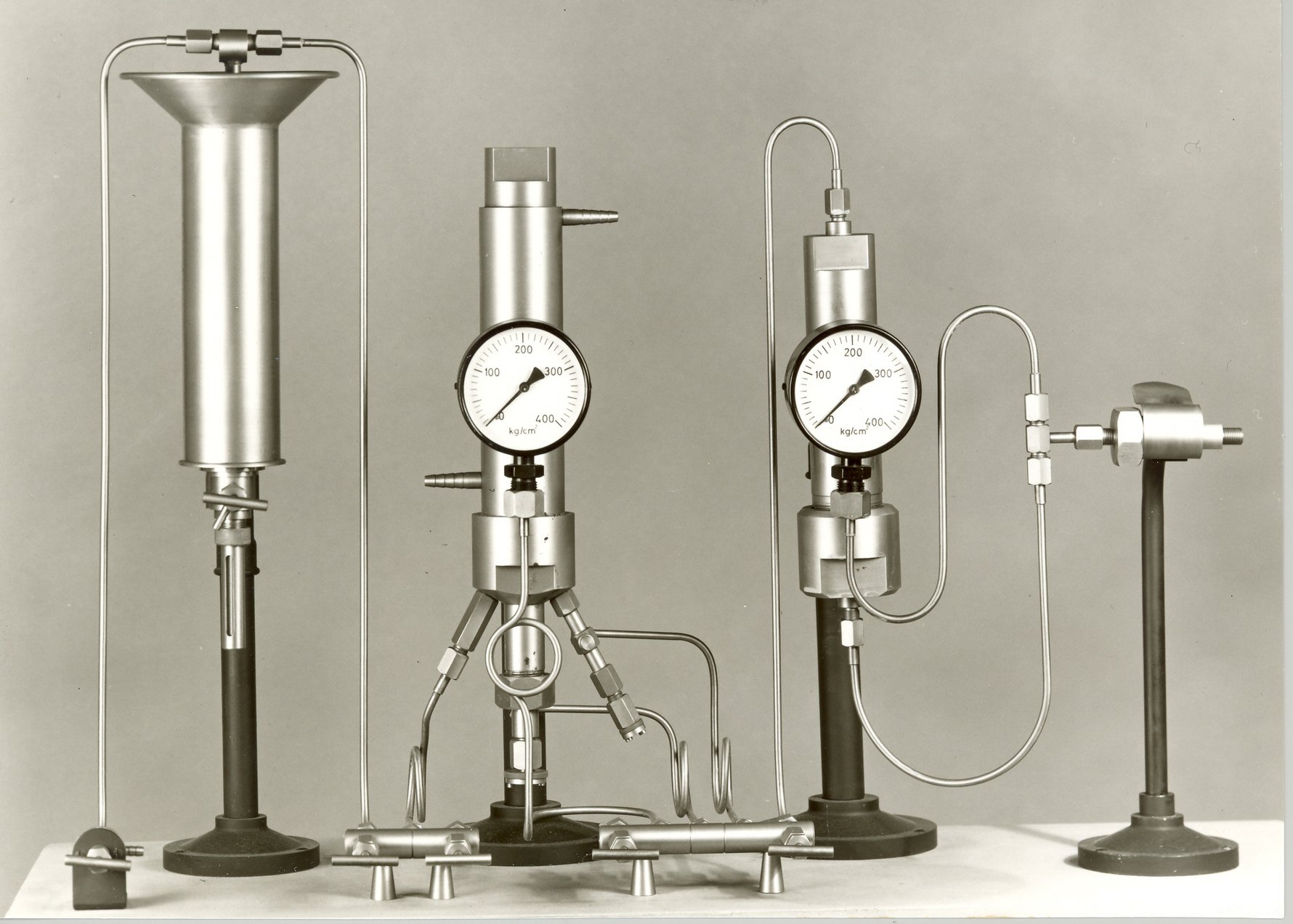

The world's demand for guano was not at all sustainable, however, and by the early-20th century, the world's precious supply of easily-mined guano lay almost exclusively in one last 355 kilometre-long, one-and-a-half metre-deep deposit off the coast of what was now Chile (to the victor go the spoils). With the Chileans holding a monopoly over the world’s ability to produce ammonia thanks to their unique ‘deposit,’ they basically had the world over a barrel and could set whatever prices they wanted. With the entire problem boiling down to the natural nitrates in the waste itself, in stepped Haber the uber-chemist. Abandoning an initial project to develop an addictive laxative for the common German house sparrow (–this is the only part we made up), Haber invented a process for producing ammonia in his lab from abundantly available nitrogen and hydrogen gas in 1911. In doing so, he accomplished a milestone in industrial chemistry and also forever changed the world economy and agriculture. Teaming with Carl Bosch at BASF, Haber and Bosch successfully scaled up the process to industrial levels and for all intents and purposes saved the world from the impending food crisis many were predicting, as suddenly inexpensive fertilisers could be made all over the globe. As a consequence they also torpedoed the Chilean economy, as the birdpoo market bottomed out, never to recover.

[Today this well-known chemical process is called the 'Haber-Bosch' process, but it was initially Haber alone who received the Nobel Prize as a result of its impact in 1918. Haber invented the process during his time in Karlsruhe, while Bosch's contribution was primarily in later upscaling the process after it was purchased by German chemical company BASF. Bosch would be awarded his own Nobel Prize in 1931, along with colleague Friedrich Bergius, for their work in high-pressure chemistry, essentially industrialising the important work Haber initiated.]

|

|

With ammonia now in abundance and the world's food security seemingly assured, what else could you do with this stuff? Well, as it happens, ammonia is also necessary in the production of nitric acid – a raw material essential for creating explosives. As such, the invention of synthetic ammonia brought with it the viable mass manufacture of explosives and ammunition. In the wake of Haber’s breakthrough, German industry charged to the forefront and the country's war machine began to rev up.

The 'Vater' of Chemical Warfare

A dutiful patriot, Haber was in no way bothered by his work becoming the backbone of the German war effort. Having been appointed director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry in Berlin, Haber placed himself and his laboratory at the service of the German government upon the outbreak of WWI. Soon Haber was a favoured behind-the-scenes military consultant, occupying himself with solving many of the country’s military concerns, and even recruiting other chemists to join. Certainly Haber’s most notorious and controversial contribution to Germany’s war effort was the development of chemical weapons, which he went about with zeal. Haber and his institute were responsible for developing chlorine gas and other deadly gases to be used in trench warfare, while also producing several improved gas mask models to protect themselves and German troops. Commonly regarded as the father of modern chemical warfare, Haber earned himself the nickname ‘Dr. Death,’ his enthusiasm for gas warfare extending so far as the organisation and personal direction of the world’s first gas attack – the large-scale release of chlorine gas on the battlefield at Ypres, France on April 22nd, 1915. Casualty estimates vary, but lie somewhere between 5,000 and 15,000 Allied wounded or killed as a result of gas, with German losses also in the hundreds (darn wind). For this success, Haber was feted as a national hero.

The Domestic Battlefield

Behind the scenes, Haber's wife Clara had been dissatified with her marriage, her lack of career and her role as a stay-at-home mother for many years. In private correspondence, she complained of Haber's 18-hour work days, his absense at home, and his "oppressive way of putting himself first in our home and marriage, so that a less ruthlessly self-assertive personality was simply destroyed." When Fritz began to apply his genius to the war and, specifically, the development of chemical weapons, Clara became utterly dismayed and went into a spiral. During this time she also suffered the loss of one of her university classmates, Otto Sackur, who died in an explosion in Fritz's lab while working with her husband on the weaponisation of chlorine gas - a position she had helped Sackur get.

Upon Fritz's return home from the 2nd Battle of Ypres - following a party celebrating his successful chlorine attack and subsequent military promotion - Clara and Fritz had an argument, after which she took his service revolver into their garden and shot herself twice in the chest, dying on May 2nd, 1915. Haber, apparently sedated by the sleeping pills he routinely took, did not hear the shots and Clara died in the arms of their 13-year-old son, Hermann. The following morning Haber left for the Eastern Front to direct the first gas attack against the Russians.

Ignoble Distinctions

Though gas warfare became a powerful psychological weapon in the war, it was never a decisive one as the Allies improved their own protective devices and retaliated. In some sense, World War I’s gas warfare became a war of the chemists with Haber finding his nemesis in France’s Victor Grignard, who worked on the detection of mustard gas and the manufacture of the chemical weapon phosgene for the Allies. For his exemplary military service, Haber was given the rank of captain by Kaiser Wilhelm – a rare distinction for a scientist too old to enlist.

and kept up a warm correspondence throughout their lives.

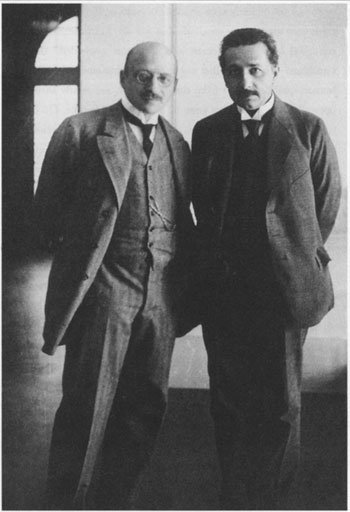

Despite being previously passed over by the Swedish Academy of Science for the Nobel Prize, Haber was ironically given the award in 1918 for his discovery of ammonia synthesis, receiving it at a time when he was widely reviled by the foreign scientific community for his war involvement. Particularly critical of Haber's conduct was his friend and colleague Albert Einstein, one of few German intellectuals to distance himself from the nationalist fervor of his home country. Beginning in 1914, Haber and Einstein would have a complex but mutually respectful relationship throughout their careers, despite disagreeing on Germany's militarism during World War I.

Before the end of the war, Haber would marry his second wife, Charlotte Nathan - a secretary about half his age - in 1917. It is speculated that the two had been having an affair for several years, the revelation of which may have been a factor in Clara's suicide. Fritz's son Hermann, now a chemist in his own right, couldn't accept his father's decision to remarry and they had a troubled relationship, much like that between Fritz and his own father. Fritz and Charlotte's marriage quickly deteriorated as well, but the couple would have two children, Eva-Charlotte and Ludwig Fritz, before divorcing in 1927.

King Midas Takes on Water

the archetype of the 'mad scientist.'

Upon Germany’s eventual defeat in the 'Great War,' Haber was devastated, manifesting the loss into an emotional burden and suffering from nervous exhaustion. Taking responsibility for his country’s failure, an increasingly unbalanced Haber hatched a plan for how to help his country pay back its enormous war reparations (brace yourselves): by extracting gold from seawater. The seemingly hare-brained scheme was based less on mystical medieval alchemy techniques than on applying to the Atlantic Ocean the concept of panning a river for gold. Although Haber's water-into-gold project was shrouded in secrecy and little today is known about it, he did publish several papers on the subject and make numerous sea voyages - it was the primary occupation of one of the world's brightest scientific minds throughout the 1920s. According to his papers, the work was actually a success, but in this instance Haber lacked a Bosch to upscale his process in a way that would make it viable. Finally, in 1928, Haber was forced to conclude that the concentration of gold in the ocean was too insignificant to make its extraction economically viable. [Perhaps a re-evaluation of the post-war guano market would have been more fruitful.]

At the same time, his institute continued their work developing chemical weapons and gases. One of their interwar creations was a cyanide gas formulation called 'Zyklon' (Cyclone), which would later come to haunt not just Haber's friends and family, but the entire European continent.

The Karmic Winds Change

By 1931, the rise of National Socialism (Nazism) in Germany had Haber on edge, and in 1933 Hitler's racist and anti-Semitic ideology began to be legislated into national policy. Although Haber had served his country with distinction in WWI and converted to Christianity (as had both his wives) over forty years earlier, his Jewish ancestry was widely known, and he was increasingly the subject of derision, suspicion and prejudice - treatment which both shocked and deeply wounded him. His health also began to suffer. As his likewise persecuted friend Albert Einstein wrote to him with a certain sympathy, but also a slight 'told-you-so' tone, Haber's reckoning with the idea that he was no longer welcome in Germany was "somewhat like having to abandon a theory on which you have worked for your whole life. It's not the same for me because I never believed it in the least."

Although he was allowed safe passage, Haber was forced to resign from his position and leave Germany in 1933. He travelled to Paris, Spain, Switzerland and eventually Cambridge, where he had been offered a position, but all of this movement was taking a toll of his health. The British scientific community treated him with understandable contempt as a result of his wartime activities, and soon after arriving in London he pivoted to accept a position as director of the newly established Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

Death Unspectacular

En route to the Middle East, Fritz Haber died in a Basel hotel on January 29th, 1934 at the age of 65. The cause of death was heart failure. Upon hearing of his passing, Albert Einstein wrote, "He was the tragedy of the German Jews, the tragedy of love spurned."

Both Haber and his first wife Clara, whose remains were moved to be close to his according to his wishes, are buried in a very modest grave in the Hörnli Cemetery in Basel, Switzerland.

Generations of Inherited Trauma

Many of Fritz's Jewish colleagues managed to escape Germany, as did Haber's second wife Charlotte and their children, who moved to London in 1933. Fritz and Clara's son, Hermann Haber, emigrated with his wife and children from France to the United States in 1941. Some of Haber's extended family were not so fortunate. By 1942, the Nazis had begun to use a cyanide-based gas called 'Zyklon B' to exterminate Jews en masse. As you've probably inferred, Haber himself developed the infamous poison, his institute creating it as a pesticide in the 1920s before it became the preferred genocide method of the Nazis. By the war’s end 1.2 million Jews were gassed to death using Zyklon B, including the children and grand-children of Haber's half-sisters.

Fritz Haber's oldest son, Hermann Haber (1902-1946), lost his wife at the end of World War II, and in 1946 he followed his mother's example, committing suicide as the fate of his relatives and the true horror of the Holocaust was being fully realised. Hermann's oldest daughter, Claire, had also become a chemist like her father, grandfather and great-grandfather before her, and was working for the US government to develop an antidote to the lethal effects of chlorine gas. When the authorities shut down her research in favour of the Manhattan Project in 1949, Claire also took her own life.

Fritz's Haber's daughter Eva-Charlotte (1915-2018), emigrated from London to Kenya just before World War II and did not return until the 1950s. His son, Ludwig Fritz ('Lutz') Haber (1921-2004), was interred on the Isle of Man during WWII due to his German nationality, then exiled to Canada, before eventually being repatriated to England. In London he earned a doctorate in economics and became an expert in the economic development of the chemical industry in Europe and North America, authoring several books on the history of chemistry, including The Poisonous Cloud: Chemical Warfare in the First World War (1986).

Comments