The material and economic cost was immense, the human cost incalculable. The Siege of Breslau had cost the lives of 170,000 civilians, and little sympathy was afforded to those that survived. Soviet revenge was swift and brutal, with reprisals against the German population going largely unchecked. Fuelled by alcohol, drunken bands of Soviet soldiers rampaged across the city, dispensing instant justice to those who resisted their looting and rape. Trapped in Dante-style anarchy Breslau had reached its lowest point, the city lost in human catastrophe. It was into this hellish vision that Polish settlers from the East arrived, desperate to find a new home.

Inventing Wrocław

The Yalta Conference of February 1945 effectively saw Stalin, Churchill and Roosevelt play Monopoly with Europe before carving her up like a stuck pig. Under terms agreed by the allied ‘Big Three,’ Poland’s pre-war borders shifted westwards, meaning that overnight what had been the German city of ‘Breslau’ for the last 75 years would become the Polish city of ‘Wrocław.’ Within days of the Nazi surrender Polish refugees were already making their way to the city, with the pre-elected Mayor Bolesław Drobner arriving on May 9th - a mere 3 days after the capitulation. Over the coming months he would be joined by thousands of people displaced from their homes in the east.

From seemingly the moment the echo of the final shots of the war had died, an intensive policy of ‘de-Germanisation’ was undertaken with absolutely anything that hinted at the city’s previous incarnation as German Breslau destroyed; the statue of Kaiser Wilhelm I which stood on ul. Świdnicka was pulled down in October 1945, a fate that was to later be shared by the fearsome post office building, a splendid structure with a history dating back to 1888. Deportations of the local German population commenced in July 1945, and by the beginning of 1948 only 3,000 remained in the city, essentially employed to train Poles in the professional arena. The year was to prove something of a landmark for Wrocław with city leaders launching a series of high-profile events to show the world how far the new city of Wrocław had progressed. The International Congress of Intellectuals, for instance, drew a crowd that included Picasso, Graham Greene, Bertolt Brecht and Irene Joliot-Curie; still, it only served as a sideshow to the year’s main event: The Recovered Territories Exhibition – an anti-German extravaganza aimed at revising the region’s history, emphasising the city’s age-old ties to Poland and highlighting the glories of the Brave New Poland.

The exhibition was to take place in Max Berg’s Jahrhunderthalle (known today as ‘Centennial Hall’), and though the name was quickly changed to the PRL-approved Hala Ludowa, or ‘People’s Hall,’ concerns remained that this monolithic German building would over-shadow the very aim of the show. In a bid to outdo it Stanisław Hempel was commissioned to create a structure that would steal the headlines. The result was a 106 metre metal spire which still stands today. Known locally as Iglica (‘The Spire’), this 44 tonne needle was erected on July 3rd, 1948 but drama was lurking just around the corner. On July 22nd Wrocław was hit by violent storms, and eight mirrors positioned atop of the tower were severely damaged, threatening to smash into the crowds visiting the exhibition below. Following weeks of debate and failed efforts to remove the danger, two students from Kraków volunteered to come and climb the structure. Setting out on the morning of October 15th their attempt was immediately thwarted by bad weather, leaving the heroic spidermen stranded halfway up. Cheered on by a crowd of thousands below, they carried on and eventually succeeded in a mission that wound up taking over 30 hours. For safety, the needle has since had ten metres shaved off its height, and currently stands at 96 metres.

The exhibition itself was to prove a roaring success. Officially opened by President Bolesław Bierut it attracted over 1.5 million visitors, the bulk of whom were left marvelling at the stirring, patriotic displays. However when the exhibition closed on October 31st, 1948, Wrocław was all but forgotten. With the celebrities and big names gone, reconstruction efforts dried up and the city was transformed into a feeder city for Warsaw. While the exhibition had made a great effort to promote Wrocław as a true Polish city, higher powers thought different in private and from 1948 onwards its primary purpose was to provide the devastated capital with building materials. Each day 200,000 bricks would leave Wrocław, a number that would later grow to a staggering 1 million. Historic buildings that had survived the war weren’t spared either, with some reports claiming ancient stretches of the city walls were demolished to aid the Warsaw rebuilding program.

That early Wrocław didn’t stagnate and die can be directly attributed to the influx of Poles who chose to settle here in the post-war years. Lured by the promise of grandiose villas and unimaginable wealth, hundreds of thousands of settlers arrived from Poland’s eastern territories, including a sizeable proportion (estimates suggest 10% of Wrocław's new inhabitants) from what is now the Ukrainian city of Lviv (Polish ‘Lwów’). They soon realised they had been sold an empty promise, but remained nonetheless, determined to rebuild the city from scratch. One of the earliest such examples of the new Wrocław can be found at the University of Technology at ul. Łukasiewicza 7-9. Designed by Andrzej Frydecki – himself a Lwów exile – this building was constructed between 1949 and 1953, and is unique for being one of the few post-war buildings in Poland that was built without adhering to the Socialist Realist style.

Reimagining the Old Town

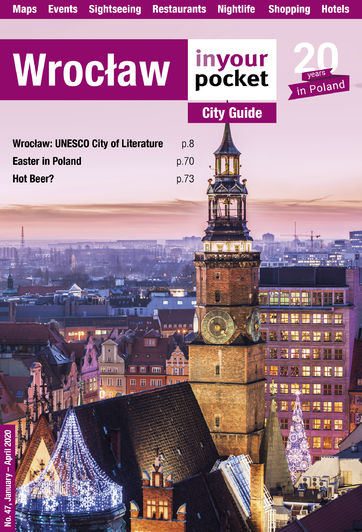

Wrocław’s greatest triumph was obviously the reconstruction of the Old Town and the buildings around the market square. Practically annihilated by the Soviet fury of 1945, the decision to ‘faithfully’ rebuild the Old Town itself came as somewhat of a surprise, especially considering the concrete monsters being raised elsewhere in PL in the aftermath of the war. ‘Faithfully’ of course meant anything but as architects Marcin Bukowski and Emil Kaliski used significant artistic licence during the works which would last from 1953-1962. Citing ideological and anti-German sentiments they refused to reconstruct any of the city’s 19th and 20th century buildings, instead choosing to give the Old Town an overwhelmingly Baroque look, utterly different from its inter-war appearance. Reconstructed burgher houses once adorned with German motifs and mottos were given a Polish language makeover, while historical buildings were restored according to original designs that predated German rule. By the same token, some buildings inexorably linked to the German past were introduced to the wrecking ball outright.

But de-Germanising the city’s aesthetic and architectural makeup wasn’t the only liberty being taken. From the beginning Wrocław’s new authorities intended to remake an Old Town for the masses, and though the buildings in and around the market square appear as though they’ve been recreated as they once were down to the last detail, many are in fact little more than socialist, utilitarian blocks beneath their elaborately decorated facades. Be that as it may, the reconstruction of Wrocław’s historic centre was one of the largest such projects undertaken in Poland after the war, and completed in what seems like record time. Not only that, but the work was executed by its adopted population with such an incredible amount of pride and skill that today Wrocław’s Old Town once again ranks amongst the most beautiful in Central Europe. In less than twenty years since sustaining a degree of devastation almost unimaginable to most visitors, the city had largely rebuilt itself. Wrocław had risen.

PRL Architecture

While the area of the Old Town was being reconstructed with respect to its historical significance, areas outside the city’s medieval centre essentially presented post-war architects with a blank slate. This apparent artistic freedom, however, was actually very much a case of “go ahead and use any colour you like, as long as it’s grey.” The officially accepted style of the time, of course, was Socialist Realism - a severe artistic style following strict guidelines from the Soviet master plan; one which architects were not allowed to deviate from. One of the most prominent examples of Stalinist architecture in Wrocław is the Kościuszko Housing Estate (Pl. Kościuszki) midway between the Old Town and the train station. Looking marvellously austere, and loosely modelled on Warsaw’s Pl. Konstytucji, this was one of the first ‘new’ housing districts to be built in the wake of the war. Constructed between 1953 and 1956 to a design by Roman Tunikowski, the uniform granite buildings have a simple classicist form and were designed to honour both patriotic and socialist ideals. However, there was always more to the Socialist Realist style than met the eye. Meticulous planning was key, and these housing estates were designed with ‘efficient mutual control’ in mind – wide streets would prevent the spread of fire, the profusion of trees would supposedly soak up an atomic blast, while the layout was such that the complex could easily be turned into a fortress if it came under attack.

More examples of this Orwellian style can be found around Wrocław's utopian-sounding Pl. Młodzieżowy development (Youth Square). Comprising Szewska, Świdnicka and Oławska Streets this project was designed to introduce more space into what had prior to WWII destruction been a tight tangle of medieval streets leading to the main square. Today the spacious courtyards, gardens and wide pedestrian boulevards are regularly used for street fairs and festivals and have actually become an iconic and essential part of the Old Town.

Also similar, but less beloved by the locals, is Pl. Nowy Targ at the north-eastern edge of the Old Town. The work of Włodimierz Czerchowski this concrete plaza was realised between 1957 and 1964, with the surrounding buildings sketched in to house 4,000 people. Czerchowski and his team did their best to honour the pre-war street plan, while making the district entirely self-sufficient; schools, shops, kindergartens and cinemas were all lined up for this area, with the intention that it would become a tightly-knit community of well-behaved communists. In reality, however, a lack of funds meant many of their brightest ideas never left the blueprints – such was the false dawn of communism. Today visitors will notice plenty more examples of communist architecture around the centre of Wrocław, including the ghastly 1960s Zeto building at ul. Ofiar Oświęcimskich 7-13, and the filthy, fish-eyed 16 storey concrete towers at Pl. Grunwaldzki 4-16, however they hardly make any more of an architectural imprint on the city’s urban landscape than any other style that has come and gone over the years. Wrocław’s downtown is incredibly architecturally eclectic today, from the Gothic Town Hall to the gargantuan Sky Tower skyscraper, but has undoubtedly developed into one of the Poland’s most important, and best loved, major urban centres.

Comments