St. Petersburg - Russia’s revolutionary capital

more than a year agoBackground to the Revolutions

The Russian economy made great industrial advances in the two decades prior to the start of World War I in 1914, but it was still under-developed and ill-equipped to supply a prolonged war. Russia’s government was still dominated by the tsarist autocracy, which claimed political authority that was divine rather than popular. The Russian people were already fractious, dissatisfied and eager for change. In 1905, their demands had taken the empire to the brink of revolution, before tensions were eased with promises of reform – promises that were never truly fulfilled.

At the epicenter of this turmoil was Nicholas II, Tsar of All Russia. Most historians agree that Nicholas was not equipped for governing Russia through difficult times. Nicholas was determined to cling to autocratic power but he was blind to the problems this created and the threats it posed to his throne. The Tsar vowed to love the Russian people, yet he turned the other way when hungry workers were shot in January 1905 and when striking miners were machine-gunned in Siberia in 1912. Nicholas preferred to blame Russia’s troubles on others, for example foreign liberal ideas, anarchists, trouble-makers in the universities and Jews. The Tsar drew his advice and counsel from an inner circle of ministers, military officers, aristocrats and bishops – but too often they told Nicholas whatever he wished to hear, rather than what he should have heard.

The rapid descent into war in 1914 had caught the Tsar unaware, mainly because Nicholas knew the German Kaiser well enough and did not think Wilhelm so treacherous that he would declare war on the empire of his own cousin. Nicholas made the first of several blunders in July 1914 when he appointed his cousin, Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich, as commander-in-chief of the army. Nicholas Nikolaevich had military training as a cavalry officer but had never commanded an army in battle; he now found himself in charge of one of the largest armies in history. At the start of the war, Russia was well poised to successfully execute the invasion of East Prussia but squabbling between and inept decision-making by Russian field commanders, Alexander Samsonov and Pavel von Rennenkampf (who detested each other) contributed to a disastrous defeat at the Battle of Tannenberg in late August 1914. Unable to face reporting the loss of 150,000 troops to the tsar, Samsonov took his own life.

From then on, it was all downhill for Russia. The losses Russia suffered in the First World War were catastrophic. Between 900,000 and 2,500,000 Russians were killed. At least 1,500,000 Russians and possibly up to more than 5 million Russians were wounded. Nearly 4,000,000 Russian soldiers were held as POWs (Britain, France and Germany had 1.3 million POWs combined). Economically Russia was devastated: 8,000,000,000 rubles in war debts were outstanding, strangling the national economy of its breath. Inflation soared, the gold reserves (then backing the currency) were nearly empty and revenues were exceedingly low while reconstruction costs were huge. Russia was on the verge of complete collapse.

The beginning of the end for the Russian royal family was spelled out in February 1917. The February Revolution, which removed Tsar Nicholas II from power, developed spontaneously out of a series of increasingly violent demonstrations and riots on the streets of Petrograd (present-day St. Petersburg), during a time when the tsar was away from the capital visiting troops on the World War I front.

On 7 March 1917 (22 February, Old Style), workers at the massive Putilov industrial plant in Petrograd came out on strike. The following day, 8 March (International Women’s Day), the women of the city, queuing in endless food queues, began to demonstrate. The word spread rapidly and within a day the whole city had been brought to a standstill by strike. Spontaneous and leaderless, the revolution had started. Crowds gathered bearing banners that read, ‘Down with the tsar! Down with the war! Down with the German woman [the tsar’s German-born wife Alexandra Feodorovna]!’

Cossacks sent to quell the revolt, if necessary by force, merely sympathized. 500 miles away in the Belarus town of Moghilev the tsar, refusing to leave the front and underestimating the extent or seriousness of the unrest, ordered in the troops. The Petrograd garrison however refused to open fire against the demonstrators, especially when so many were women, electing instead to join their ranks. It was whole-scale mutiny against the tsar. Workers established workers’ councils, or ‘soviets’, determined to bring an end to the tsar’s autocracy.

Finally, after failing to heed the desperate pleas for action from the Duma to face the situation and respond to the demonstrators’ demands, the situation became completely and utterly out of control. On 15 March 1917, the tsar was on his way back to the capital, but his train had been held up at the town of Pskov. His situation was hopeless – he had lost the support of the people and the loyalty of his military. Representatives of the army and the new government came to meet him. Realizing he had no alternative, Nicholas announced his abdication. Thus, after 304 years, the Romanov dynasty had come to an abrupt end with few mourning its passing.

Though the February Revolution was a popular uprising, it did not necessarily express the wishes of the majority of the Russian population, as the event was primarily limited to the city of Petrograd. However, most of those who took power after the February Revolution, in the provisional government (the temporary government that replaced the tsar) and in the Petrograd Soviet (an influential local council representing workers and soldiers in Petrograd), generally favored rule that was at least partially democratic.

The 1905 Revolution and the February Revolution of 1917 were precursors for the final revolution that would change Russia irreversibly. The October Revolution (also called the Bolshevik Revolution) overturned the interim provisional government and established the Soviet Union. On November 6 and 7, 1917 (or October 24 and 25 on the Julian calendar, which is why this event is also referred to as the October Revolution), leftist revolutionaries led by Bolshevik Party leader Vladimir Lenin launched a nearly bloodless coup d'état against the provisional government. The Bolsheviks and their allies occupied government buildings and other strategic locations in Petrograd and soon formed a new government with Lenin as its head. Lenin became the dictator of the world’s first communist state.

The October Revolution was a much more deliberate event, orchestrated by a small group of people. The Bolsheviks, who led this coup, prepared their coup in only six months. They were generally viewed as an extremist group and had very little popular support when they began serious efforts in April 1917. By October, the Bolsheviks’ popular base was much larger; though still a minority within the country as a whole, they had built up a majority of support within Petrograd and other urban centers.

After October, the Bolsheviks realized that they could not maintain power in an election-based system without sharing power with other parties and compromising their principles. As a result, they formally abandoned the democratic process in January 1918 and declared themselves the representatives of a dictatorship of the proletariat. In response, the Russian Civil War broke out in the summer of that year and would last well into 1920.

Traces of the revolutions in modern day St. Petersburg

History buffs can stroll around St. Petersburg - the cradle of the Russian Revolution - for days in order to see with their own eyes the places that played such a pivotal role in our country's history. Here are the must-see places where you can really immerse yourself in St. Petersburg's revolutionary past.

A good starting point is the Cruiser Avrora, the famous Russian ship and symbol of the Russian Revolution. It was her salvo that gave the signal for the storming of the Winter Palace on the night of 7-8 November, 1917 bringing the Bolsheviks to power in a coup that changed world history. Aurora is also the oldest surviving ship of the Russian Navy, having fought during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, WWI and during the Great Patriotic War her canons were used to defend Leningrad. Now the Aurora is a branch of the Central Naval Museum at the Petrogradskaya nab. The exposition of the museum ship is located throughout six rooms. There are about 300 museum objects including model ships, paintings, objects of seamanship and life at sea, documents and photographs.

The State Museum of the Political History of Russia is the successor to the Revolution Museum. It is housed in two historic buildings of the modern era: the mansions of the ballerina M. Kschessinskaya, and baron V. Brandt. Mathilda Kschessinskaya, prima ballerina of Mariinsky Theater, had good relations with the royal family, which made her leave the country during the revolutionary days of February 1917. First the mansion was occupied by the Petrograd armored division and later by different revolutionary organizations. It had been decided in 1954 that Kschessinskaya Mansion would house the State Museum of Revolution, which was renamed to The State Museum of the Political History of Russia in 1991.

The storming of Winter Palace was one of the key events of the October Revolution because this is where the Bolsheviks seized the residence of the Provisional Government on the night from October 25 to October 26, 1917, resulting in its overthrowing and its members’ arrests. The Winter Palace was also the stage for Bloody Sunday in 1905 so, naturally, this monumentally important square should not be missed.

From its very founding the Peter and Paul Fortress, the original citadel of St. Petersburg, had been used as a political prison. Hundreds of Russian revolutionaries had gone through it, including Vladimir Lenin's brother Alexander Ulyanov. During the October Revolution, the garrison of the fortress took the Bolsheviks' side. After the storming of the Winter Palace and the arrest of the Provisional Government, its ministers became the prison's new convicts.

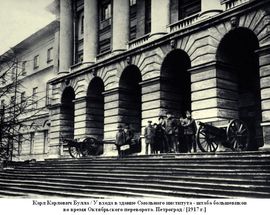

Up to 1917 the neoclassical edifice on Smolny proezd 1, designed by Giacomo Quarenghi, belonged to Smolny Institute for Noble Ladies, Russia's first educational establishment for women. After the Institute had been shut down, the building was turned into the headquarters of the Petrograd Soviet. On October 25, 1917, the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets took place in Smolny and the first Soviet Government led by Vladimir Lenin was formed. In the 1920’s a public garden was laid out and a monument to Vladimir Lenin was raised in front of the Smolny.

In the middle of Marsovo Pole (Field of Mars) you will find the monument "To the Fighters of The Revolution" and the eternal flame commemorating those who had fallen in fights and battles of the February and October revolutions as well as those who perished in the Russian Civil War. On November 6, 1957, the country's first eternal flame, transferred from the furnace of the "Kirov factory" was ignited on Marsovo Pole.

The Lenin statue at Finlyandsky Vokzal has quite a bit of Soviet legend attached to it. It was here that Lenin returned from exile in April, 1917, in a sealed carriage drawn by a train that was a gift from Finland. The train is displayed here in a glass pavilion. Out front, there is a majestic statue of Lenin pointing the way to a radiant future. At the entrance to the adjacent metro stop there is also an impressive mosaic of Lenin.

The Alliluev Apartment Museum is often referred to as "Lenin’s secret flat". Lenin actually only lived here for 3 days in July 1917 while he and the other Bolsheviks thought of a better place to hide. It’s a plain and cold place sparsely furnished with paintings of Lenin in heroic poses and his voice (coming from an old gramophone) swirls around the rooms. It’s actually more famous for being the home of Stalin’s wife Nadezhda Allilueva and thus has a very eerie atmosphere.

Revolutionary St. Petersburg in popular culture

The tragic nature of the revolutions, the fearlessness displayed by those involved in them and their historic impact make a for a great cinematic plot. Many Russian/Soviet as well as foreign directors could not resist putting the events of 1905-1917 into films that keep the audience on the edge of their seat.

Perhaps the most famous movie both at home and abroad about the Revolution is Sergei Eisenstein’s “Battleship Potemkin”. After the success of “Strike” (1924), Sergei Eisenstein was commissioned by the Soviet government to make a film commemorating the uprising of 1905. Eisenstein's scenario focused on the crew of the battleship Potemkin. Fed up with the extreme cruelties of their officers and their maggot-ridden meat rations, the sailors stage a violent mutiny. This, in turn, sparks an abortive citizens' revolt against the Tsarist regime. The film's centerpiece is staged on the Odessa Steps, where in 1905 the Tsar's Cossacks methodically shot down rioters and innocent bystanders alike. “Battleship Potemkin” is Soviet cinema at its finest and its montage editing techniques remain influential to this day.

Following the success of “Battleship Potemkin”, the Soviet government commissioned “October: Ten Days That Shook the World” for the tenth anniversary of the October Revolution. This 1928 silent historical film by Sergei Eisenstein and Grigori Aleksandrov is a celebratory dramatization of the 1917 October Revolution. Originally released as October in the Soviet Union, the film was re-edited and released internationally as Ten Days That Shook the World, after John Reed's popular book on the Revolution.

“Lenin in October” is a 1937 Soviet drama film directed by Mikhail Romm and DmitriVasilyev. Made as a Soviet-realist propaganda work by the GOSKINO at the Mosfilm studio, it portrays the activities of Lenin at the time of the October Revolution. Josef Stalin was given a more prominent role in the film than he actually played in real life events of the time; after his death, all his scenes were expunged from the film for its reissue in 1958.

“Reds” is a 1981 American epic drama film co-written, produced and directed by Warren Beatty. The picture centers on the life and career of John Reed, the journalist and writer who chronicled the Russian Revolution in his book Ten Days That Shook the World. Beatty stars in the lead role alongside Diane Keaton as Louise Bryant and Jack Nicholson as Eugene O'Neill.

“Doctor Zhivago” is a 1965 British-Italian epic romantic drama film directed by David Lean. It is set in Russia between the years prior to World War I and the Russian Civil War of 1917–1922, and is based on the Boris Pasternak novel of the same name. While immensely popular in the West, the book was banned in the Soviet Union for decades. For this reason, the film could not be made in the Soviet Union and was instead filmed mostly in Spain.

Even now the events of 1917 inspire cinema around the world. "Sunstroke", a 2015 film by Oscar-winner Nikita Mikhalkov, is based on the eponymous story by Ivan Bunin and his diaries "Cursed Days",in which the author depicts the revolution as a catastrophe. The film has divided Russian society.

"Angels of the Revolution" (2014) is an unusual story of the consequences of the revolution filmed by Venetian Film Festival-winner Alexei Fedorchenko (First on the Moon, Silent Souls). It's about a group of revolutionaries who come to the taiga to "enlighten" the indigenous peoples in the name of art. Fedorchenko's screen heroes are based on 1920s avant-garde artists: Painters, architects, musicians and others.

In 2017, Britain's Margy Kinmonth released a very interesting film titled “Revolution – New Art for a New World” about the Russian avant-garde. It examines the roots of this new art, born of revolution and its ties to politics. “There are many points of view on the revolution told by a lot of people, but the story has never before been told by the artists,” Kinmonth explained. The movie offers an introduction for those who know little about the Russian avant-garde but want to find out more. Kinmonth uses leading curators and museum experts, including Hermitage director Mikhail Piotrovsky and head of the Tretyakov Gallery Zelfira Tregulova, as guides to this fascinating world.

Museum of Political History of Russia

Ul. Kuibysheva 2-4 (entrance from Kronversky pr.)

/st-petersburg-en/museum-of-political-history-of-russia_9503v

The State Museum of the Political History of Russia is the successor to the Revolution Museum. It is housed in two historic buildings of the modern era: the …

/st-petersburg-en/winter-palace-of-peter-the-great_147729v

Exhibition complex of the State Hermitage. The Winter Palace of Peter the Great is a unique architectural monument of the first quarter of the 18th century. …

Comments