A steep staircase takes you to the entrance of an imposing, almost brutalist brick building, with patinaed steel letterwork and a Strelitzia flower – the logo of the South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI) – to signal you've arrived. Tucked away on the garden's grounds and accessible to visitors by appointment only, the National Herbarium is a vital space supporting research, conservation, and education far beyond its walls.

Photo: Johannesburg In Your Pocket.

It is central to SANBI's broader mission as custodians of South Africa's plant diversity: an institute that devotedly goes about its business of managing some of the most beautiful gardens in the country, from Walter Sisulu National Botanical Garden in Roodepoort to Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden in Cape Town.

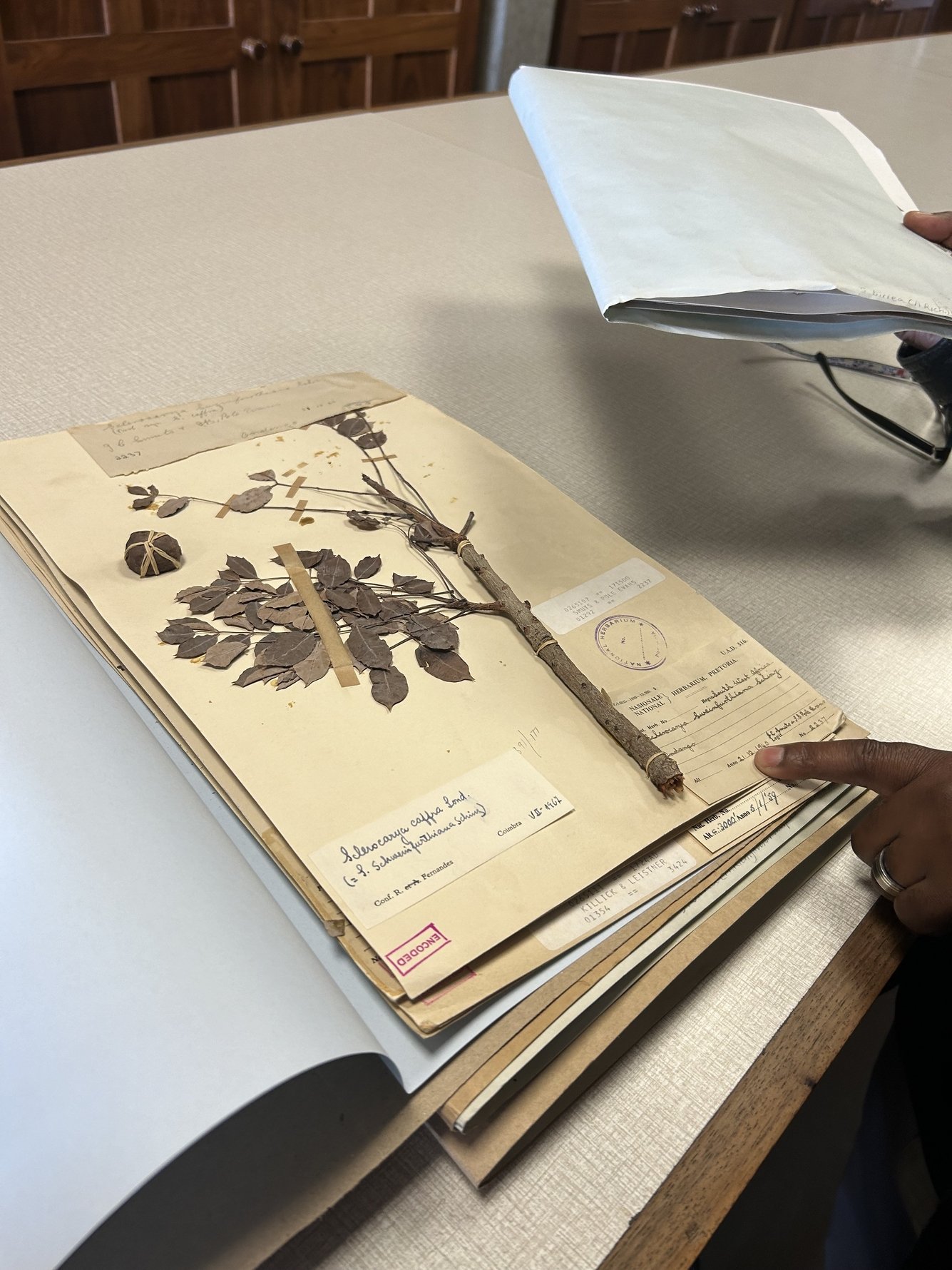

Stepping inside the National Herbarium feels like entering a time capsule. The dried specimens, affixed carefully to their mounting boards, may appear static – but the plants here hold stories about the people who encountered them and the landscapes they once inhabited. Currently, a mass digitisation process is underway to catalogue the herbarium’s vast collection – the second largest in the southern hemisphere. A mammoth task, as we came to understand on our visit (July 2025), that is expected to reach completion in the next four to five years.

1.3 million plants, and counting

Pretoria National Botanical Garden. Photo: Johannesburg In Your Pocket.

Beyond its nondescript exterior, it struck us that the National Herbarium wouldn't be out of place in a Wes Anderson film (if he made one about plant science) – with the requisite mix of order, symmetry, and quirky details. Within these walls, innumerable metal file drawers and rows upon rows of wooden cabinets are brimming with natural treasures. From personal ornaments to handwritten notes, wandering eyes will collect clues of the people who have passed through this space.

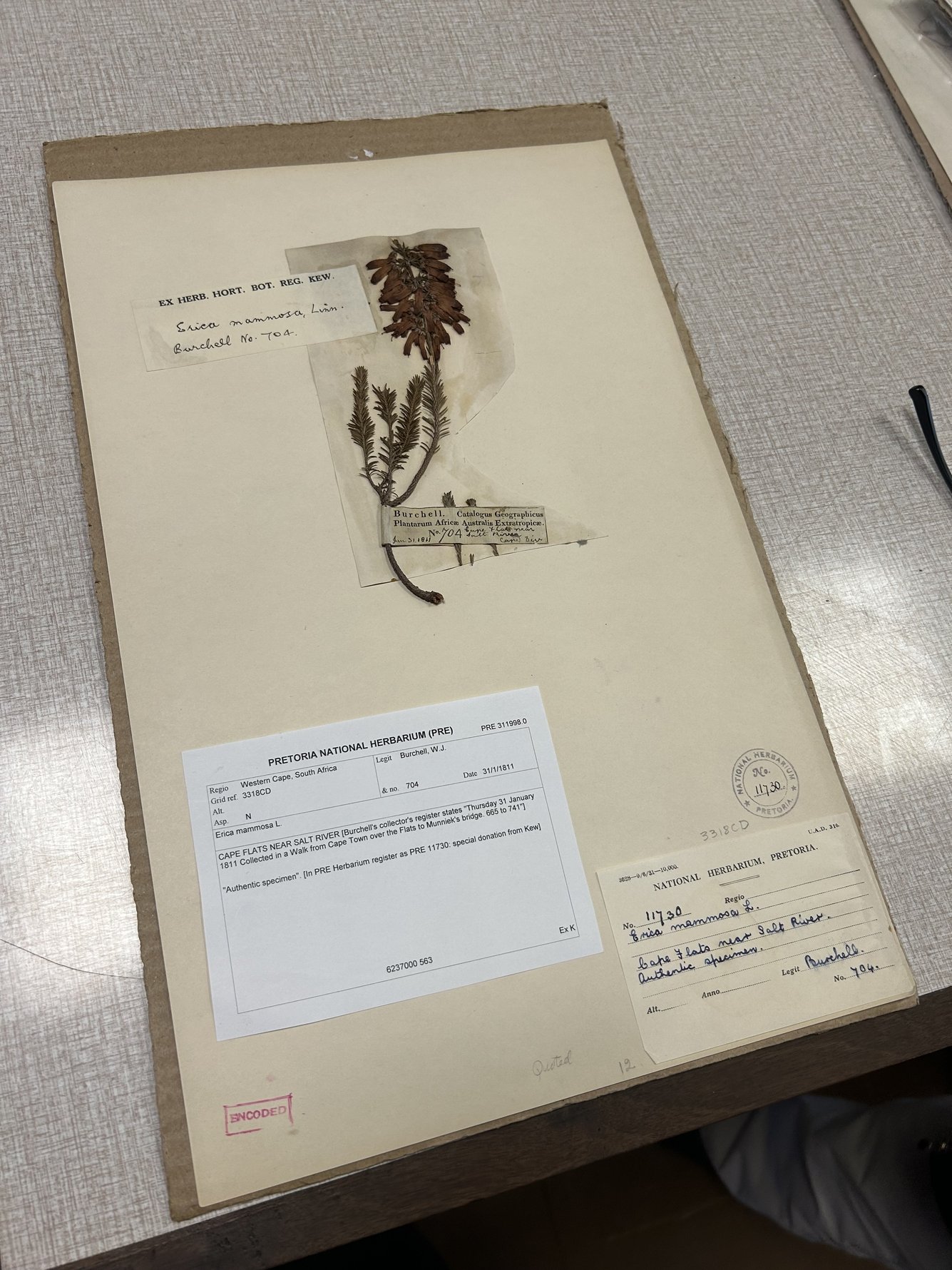

Over the years, the National Herbarium has inherited plant collections from across South Africa. Its oldest specimen dates back to 1811, collected by the explorer and naturalist John William Burchell in the Cape Flats. Today, the herbarium houses more than 1.3 million dried, pressed plant specimens representing over 30,000 species. Each is carefully labelled, dated, and often annotated with location details, collector names, and field notes.

Photo: Johannesburg In Your Pocket.

Some of the specimens come from well-known – and sometimes surprising – figures. As the herbarium's information officer, Mashiane Mothogoane, gave us a tour of the facilities, he more than once pulled out pressings from Jan Christiaan Smuts, South Africa’s former Prime Minister and an avid amateur botanist. (Plants from Smuts' personal collection are also on display at the Jan Smuts House Museum in Irene.)

This staggering collection of archival material includes everything from ferns to succulents to delicate orchids, and reflects South Africa’s extraordinary plant diversity. As the third most biodiverse country on Earth, South Africa is home to nearly 10% of the world’s plant species, many of which are found nowhere else. Among them are two globally unique floristic regions – the Fynbos and Nama Succulent Karoo. "The kind of work we do is important because we are able to tell that story to the world," says Mothogoane.

Photo: Johannesburg In Your Pocket.

Some plants in the collection are now extinct in the wild, known only from preserved specimens, while new species are still being discovered. We heard that it's not uncommon for the herbarium's staff to take along a plant press when they go on holiday, just in case.

The naming of new species follows strict international rules but also reveals the more playful and human side of science. Some are named for people – Smutsiae, for Jan Smuts – some for places –Transvaalensis, Karooana – and others for characteristics, like brevi-flora, meaning "short flower". The Vuvuzela flower was named during the 2010 FIFA World Cup for its resemblance to the iconic stadium horn.

A deeply rooted history

Photo: Johannesburg In Your Pocket.

Long before it became known as the National Herbarium, this institution traces its roots back to 1903 in response to an agricultural crisis. At the time, South African farmers were losing livestock to toxic plants they couldn’t identify. The Department of Agriculture enlisted Joseph Burtt Davy – a British-born agronomist working in the US – to help build a scientific understanding of the country’s vegetation.

Davy arrived in Pretoria on May 1, 1903. By the very next day, he was out in the veld (wild bush) with a plant press, collecting specimens around the site where the Union Buildings now stand.

Photo: Johannesburg In Your Pocket.

As the scale and scope of this project grew, the herbarium's operations moved from the Volkstem Building to Vredehuis, and eventually to its current home in the Pretoria National Botanical Garden in Brummeria. This final move, led by then-director Dr Robert Allen Dyer, marked a turning point in the institution’s evolution and its growing national significance. (Today, visitors to the garden can still find a plaque honouring Dyer’s contributions.)

More than a century after Davy’s first field expedition, the National Herbarium is now part of the South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI), established in 2004. It stands as one of the oldest herbaria in the Southern Hemisphere, the largest in Africa, and a global centre for plant research, conservation, and biodiversity science. Mothogoane tells us, "The National Herbarium is at the core of the whole organisation, it laid the groundwork for what SANBI has become."

Why this work matters

Today, the National Herbarium is central to SANBI’s role as the custodian of South Africa’s plant biodiversity. Its collection is preserved, studied, and made accessible to a global scientific community.

Beyond the drawers of dried plants, however, the National Herbarium plays a powerful role in shaping life in South Africa in both subtle and significant ways. The work done here informs everything from conservation and climate planning – using 200 years of data to map out how local ecosystems shift over time – to Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) that can pause or redirect new developments.

Photo: Johannesburg In Your Pocket.

It also supports research into traditional medicines and informs more resilient farming practices, safeguarding food security. Not straying too far from its origins, the herbarium still offers plant identification – including the poisonous kinds – and, through evidence like pollen, even contributes to forensic investigations. These include cases related to the illegal poaching of rare and sometimes endangered flora, with succulents particularly at risk. According to Yale.edu, "Millions of plants have been illegally dug from the Succulent Karoo, resulting in the functional extinction of at least eight species."

We have far from exhausted the far-reaching scope of the herbarium's work, but it is remarkable how much we have to glean from South Africa's richly diverse plant life and what these unsung heroes can teach us. "South Africans don't know what treasures they have in the country. We need to appreciate what we have," Mothogoane says.

Herbarium, in your pocket

to process thousands of plants daily. Photo: Johannesburg In Your Pocket.

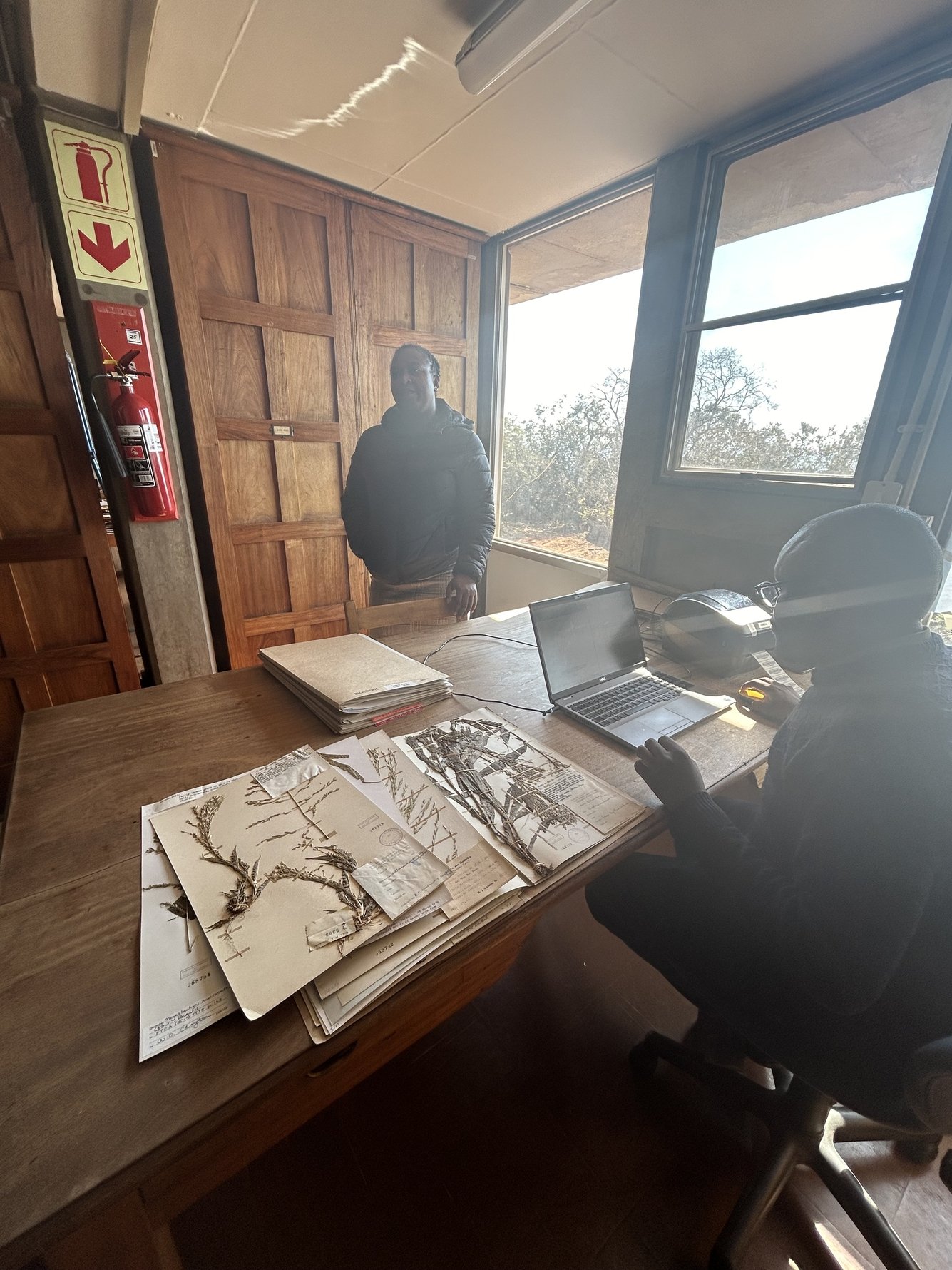

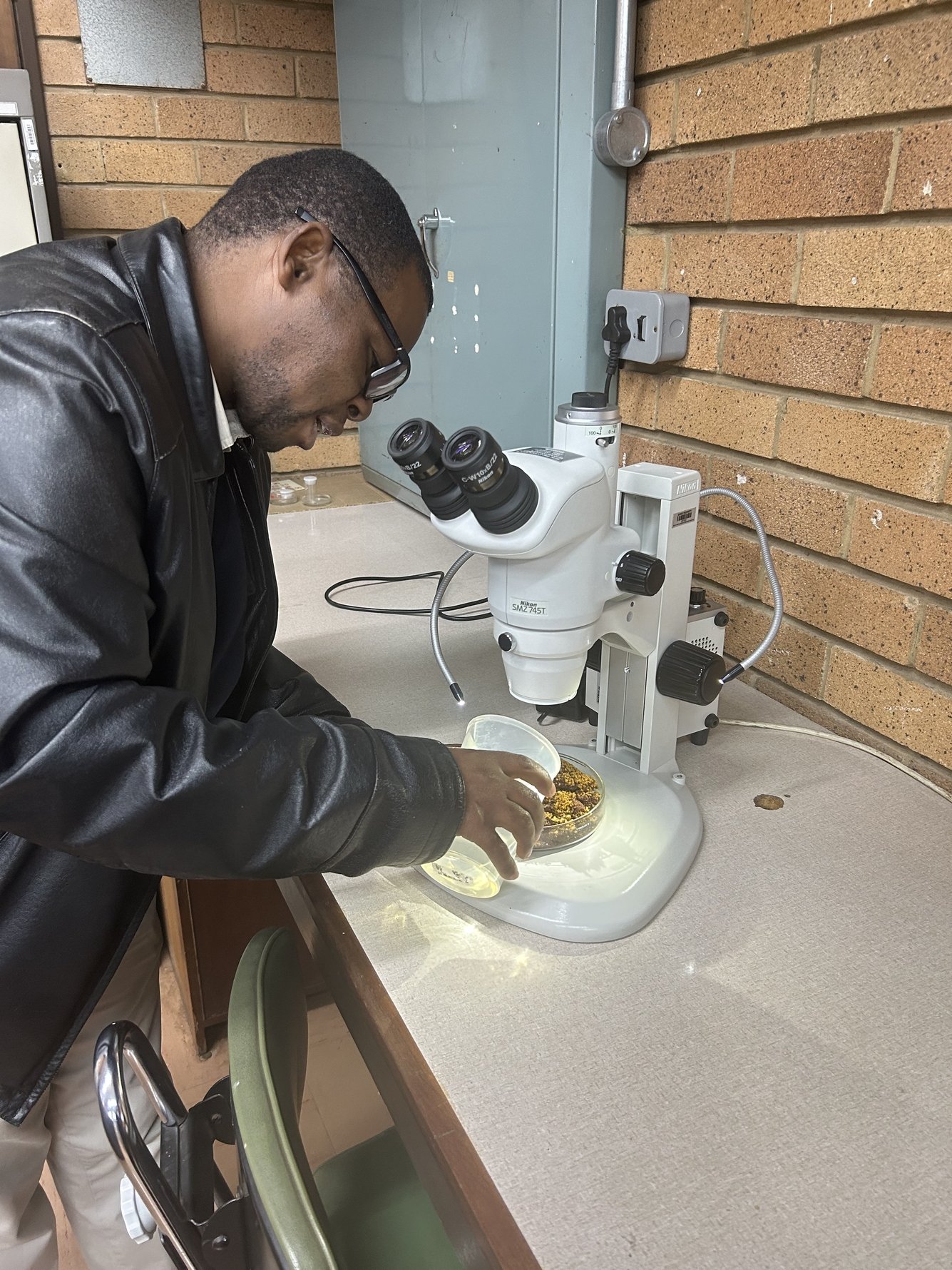

At the heart of our visit to the National Herbarium was a glimpse into its mass digitisation project. The goal? To digitally capture 1.3 million plant specimens online by 2030. No small feat. Yet thanks to the herbarium's new-and-improved scanning system, it's becoming a reality. This technology allows thousands of plants to be processed daily – a major upgrade from the inverted flatbed scanner that was previously used.

The inverted flatbed scanner played a key role in the herbarium's first large-scale imaging effort in 2003 as part of the African Plant Initiative. The initial phase focused on scanning "type specimens" – the definitive reference samples for plant species. To protect the fragile specimens, they couldn’t be laid directly on the scanner glass. Instead, the scanners were flipped upside down and mounted on pedestals while each pressing was carefully lifted into place. Even with this workaround, the team could only digitise around 40 specimens per day – a pace that, given the collection’s vast size, would have taken generations to complete.

Photo: Johannesburg In Your Pocket.

That foundational project has evolved into a much larger endeavour to catalogue the herbarium’s entire collection. The new conveyor-belt imaging system we saw in action captures high-resolution images every seven seconds. Still, each specimen must be meticulously prepared beforehand, which remains a time-consuming step. During our visit, the team – led by herbarium manager Erich van Wyk – was focused on ferns and monocots, the first groups of plants to undergo complete digitisation. No sooner were these specimens photographed than their portraits were pulled up on the computer screen in dazzling detail.

For all their scientific merit, these scans are equally beautiful – they look like fine art prints. Plant-lovers and the creatively inclined should browse SANBI's growing archive on JSTOR Global Plants to find a trove of botanical inspiration. Beauty notwithstanding, digitising the herbarium's collection reduces the need to physically handle the fragile specimens or ship them overseas, while making South Africa's plant collection accessible worldwide.

As Van Wyk emphasises, "Important decisions about the environment are being made today. We can’t wait decades for the data needed to manage and conserve nature effectively. This information must be available now, especially as we face climate change, pollution, and other environmental challenges." Looking ahead, the National Herbarium plans to incorporate emerging technologies like image recognition and analysis to further enhance the collection’s research potential, ensuring this historic repository remains a vital resource for generations to come.

Visiting the Pretoria National Botanical Garden

The National Herbarium is open to visitors by appointment, email national.herbarium@sanbi.org.za. Beyond this, the herbarium's setting within the Pretoria National Botanical Garden makes for a rewarding day trip. Spanning 76 hectares, the garden features a significant portion of protected grassland, with only 46% of the area cultivated – an important exercise in conservation. Visitors can explore a diverse range of indigenous flora, from a striking succulent garden to a rare cycad forest. Don’t miss the vibrant Ndebele-painted huts, which mark the entrance to the medicinal plant walk – home to healing plants, hunger suppressants, and the thirst-quenching spekboom.

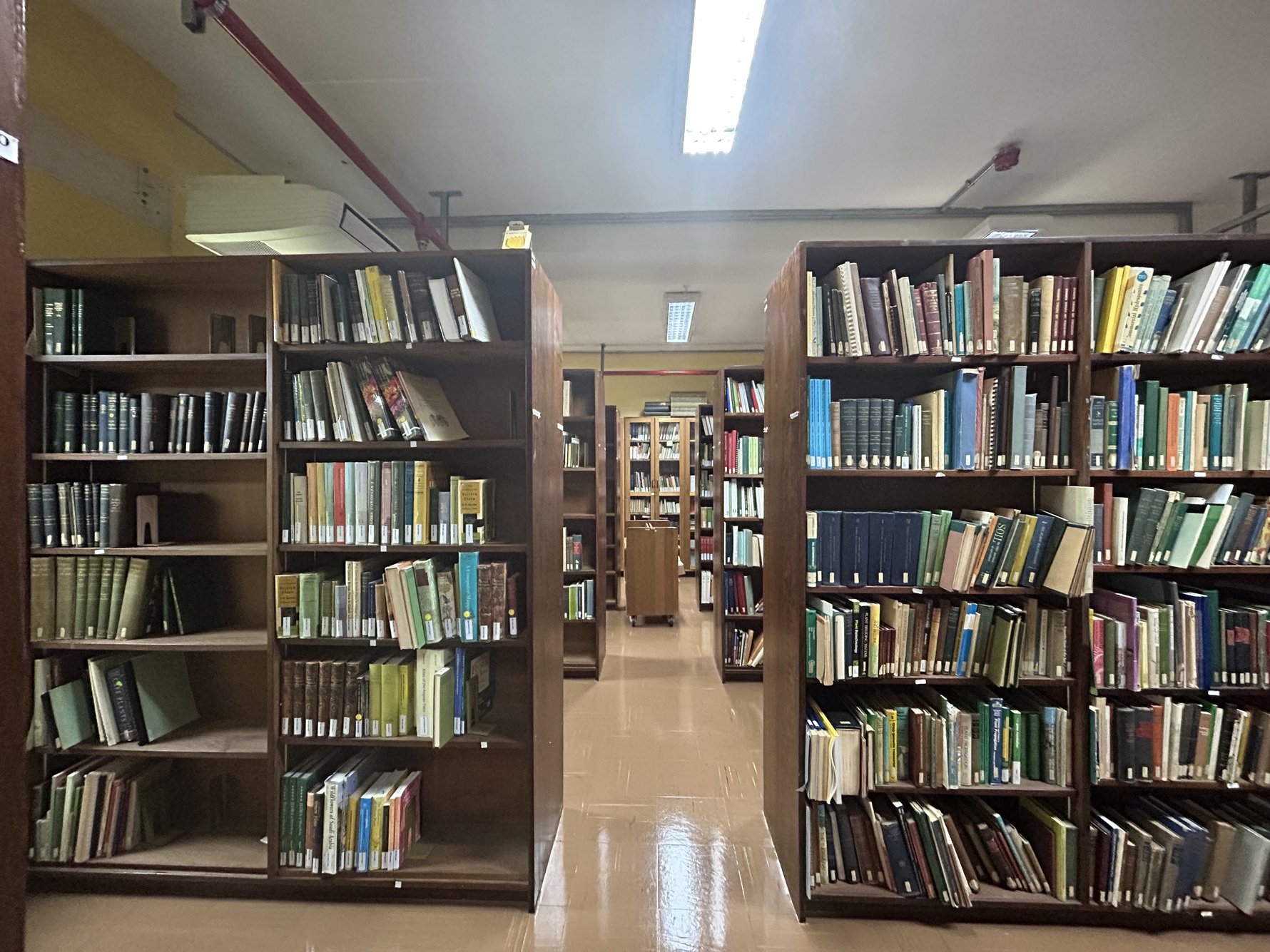

The scholarly inclined can book an appointment to visit the historic Mary Gunn Library, an institution nearly as old as the herbarium itself. Established by its namesake in 1916, this library holds more than 18,000 books, including rare antiquarian books and important Africana, making it one of Africa's foremost botanical and biodiversity resources. To arrange a visit to the Mary Gunn Library, email j.chauke@sanbi.org.za or call +27 12 002 5389. The nearby SANBI bookshop also stocks a wide range of publications.

For more to do at the Pretoria National Botanical Garden, check out our visitor's guide.

_m.jpg)

_m.jpg)

_m.jpg)

Comments