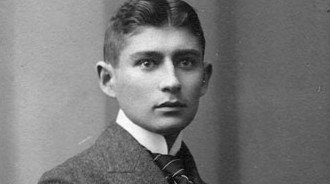

Kafka was born into a Jewish family on July 3, 1883 at U radnice 5, a house on the corner of Maiselova and Kaprova - a border between Staré Město and Josefov. There is a plaque on the building now and a small exhibition inside the house. Prague at that time was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and German was Kafka’s first language, despite his Jewish roots and Czech background. As a boy Kafka lived in the Minute House, U Minuty, the black and white graffitioed building that is part of the Town Hall on Staromětské nám. For some time he lived in an apartment, by all accounts a pretty substandard place, within the building that now houses the American embassy over in the Schornbornsky palac at Tržistì 15. He also lived for a time in another street off Staromětské nám, Týnska 3.

Kafka worked for the Worker’s Accident Insurance Company (Na Poříčí 7) on what is now one of Prague’s high streets. The building today is the Hotel Century Old Town. Another hotel connected to his work is the former Grand Hotel Evropa on Wenceslas Square. One of his first public readings was held here (then called Hotel Erzherzog Stefan) in 1912. He read from The Judgement. In 1923, he made the big decision to move to Berlin so he could focus on his writing. It was there that the tuberculosis he had struggled with for years returned. He had first caught the disease in 1917 and when it returned in 1923, he was forced to retire from the insurance company. He travelled to Vienna for treatment in a sanatorium and it was there he died on June 3, 1924.

Like many a struggling artist, Kafka was not appreciated until after his death. Most of his work was published posthumously by his good friend and literary executor Max Brod, who plays a large role in why we even know who Kafka is today. Stories published before his death include the popular “The Metamorphosis,” “Before the Law” and “The Judgement” along with a few collections like “Mediation” and “A Hunger Artist.” His self-doubt though led him to struggle with his writing and publishing and he begged Brod to destroy any unpublished manuscripts after his death. Brod did not follow these instructions and instead went on to publish Kafka’s “The Trial,” “The Castle” and “Amerika,” among others.

Aficionados can make a pilgrimage to his grave, at the New Jewish Cemetery (Židovské hřbitovy; Želivského metro) where he is buried next to his parents. Kafka's grave is N°137. There are typically a few fans visiting his grave to commemorate the date of his death.

A bronze sculpture was unveiled in December 2003 in honour of Kafka. It is located next to the Spanish Synagogue in Josefov. However, there’s a more monumental (literally) monument to the writer in Prague. Located behind the Tesco department store at Národní 26, it’s a huge reflecting, rotating Kafka head. Designed by local artist David Černý, it’s nearly 40 feet tall and made up of just over 40 moving chrome plated layers.

The Kafka Museum opened in 2005 and offers an in-depth look at Kafka’s connection to the city. The museum presents Prague as a city full of the strange tales that were influential on Kafka’s work. If you are determined to make your trip to Prague completely Kafkaesque, book a bed at the Hostel Franz Kafka and pop in for a coffee at the Franz Kafka Café. Cafes in Kafka’s times were the place for intellectuals to meet, and one of the writer’s favourite haunts was (F-9), Café Louvre, a probably much better café choice than the one that bears his name.

Comments