|

|

|

|

The Christianisation of Poland - 966CE

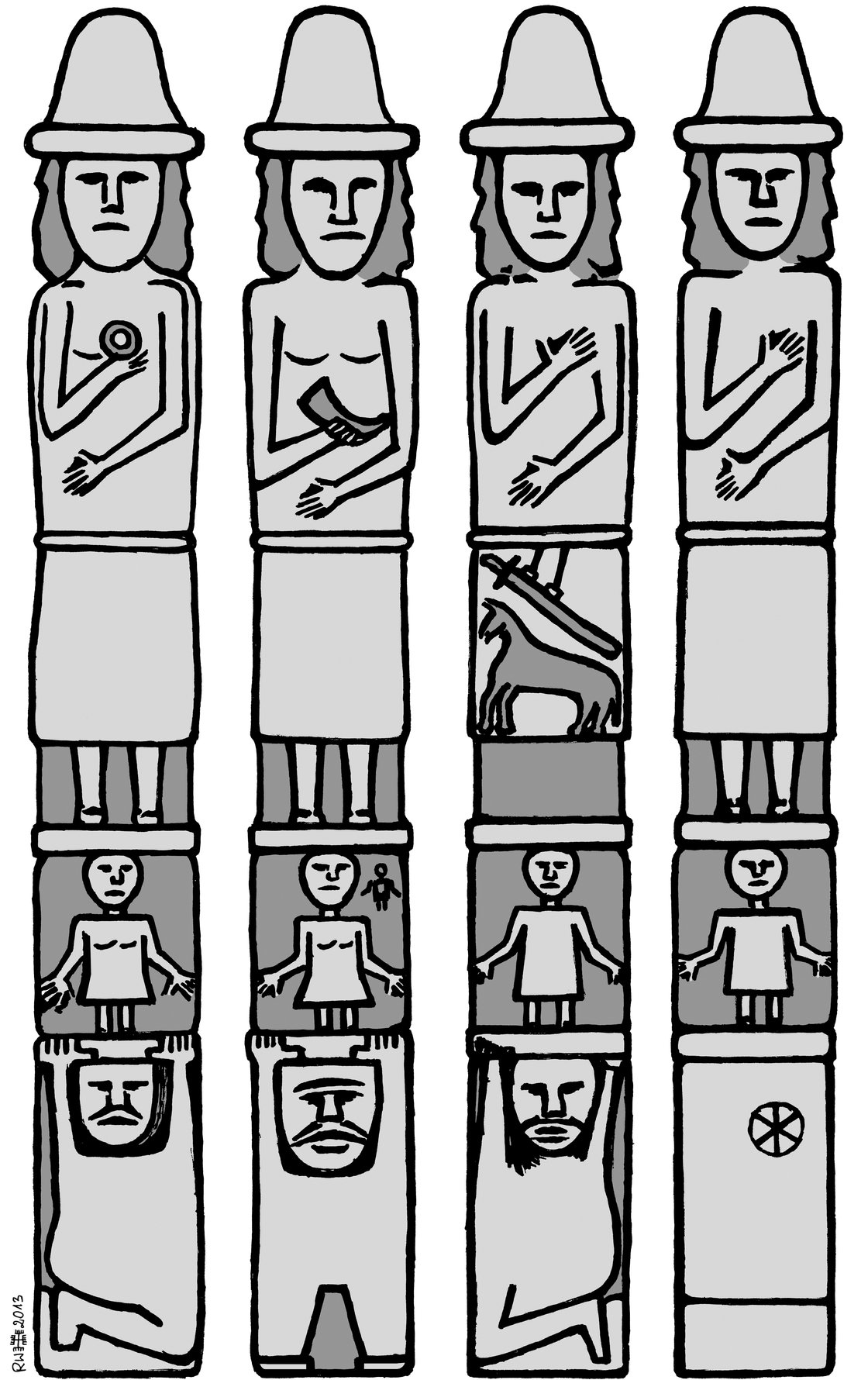

This all changed in the year 966CE when Duke Mieszko I, who had united a number of pagan Slavic tribes with the hope of solidifying a sovereign state, married a Czech princess named Dobrawa. As marriages went back then, the purpose of this union was to strengthen political ties and, in this case, Mieszko was seeking support from Dobrawa's father, Boleslav I the Cruel, the leader of Bohemia (now a region of Czech Republic). In order to seal the deal, Mieszko was expected to convert to Catholicism, along with his followers. Mieszko's conversion was, no doubt, convenient in winning the favour of other Catholic states to the west, though it has also been suggested that the pagan priest class amongst the Lechtian tribal groups held a lot of influence and embracing a new religion would effectively set himself and his court apart. The ceremony took place on the Holy Saturday of 14 April 966, a date which is agreed as being the foundation of the state known as Poland. Although the exact location is still disputed by historians, the capital Gniezno and Poznań in Wielkopolska (ENG: Greater Poland) are the most likely sites.The statues in this image are inaccurately-portrayed in a Greco-Roman style, compared to the primitive form of the Zbruch idol!

The Pagan Reaction

After Mieszko's passing, his son Bolesław the Brave, who crowned himself King in 1025, expanded the infrastructure of the Church throughout the Kingdom and turned Poland into a state that was taken seriously by its neighbours. Bolesław also sent the missionary Adalbert of Prague north to the frontiers of the Baltic coast in an attempt to convert the Old Prussians (not to be confused with the German Kingdom of the 18th/19th Century). In 997CE, the Prussians responded by cutting off Adalbert's head, which set the pace of diplomatic relations for the next few centuries!

There were other influences to this period of instability. Bolesław the Brave's son and successor, Mieszko II, waged an unsuccessful war against the Holy Roman Empire and then a civil war against his brothers Bezprym and Otto. His death, probably an assassination, in 1034 is believed to have been the tipping point. The pagan uprisings are said to have completely ruined Wielkopolska, so much so that the capital was moved from Gniezno to Kraków in 1038. Mieszko II's son, Kazimierz the Restorer, spent years in exile in Germany and Hungary until he negotiated with the Holy Roman Empire and gained support from his Brother-in-law Yaroslav I the Wise, the Prince of the Kievan Rus (now Ukraine/East Poland). His title 'the Restorer' is testament to the fact that he was able to reinstate Masovia, Silesia and Pomerania as Polish territories. The pagan reaction had, effectively, been subdued.

The Prussian Crusade

Back up in the north, little progress was being made converting the Old Prussians. For the next two centuries, the Prussians successfully held off a number of more-advanced Polish armies using guerilla tactics. Land in Pomerania would be lost and quickly regained due to stiff resistance. Realising that they couldn't do it alone, Konrad I of Masovia, the High Duke of Poland, called in the Order of Teutonic Knights for support in 1226. Recently evicted from their residency in Hungary, the Teutons were offered land around Chmielno in exchange for dealing with the pagan tribes encroaching on Polish territory. At this point, the Pagan tribes of the Baltic coast were outmatched, yet they still continued fierce resistance. For the Teutonic Knights, it must have been clear that no quarter should be given. By 1274, the Prussians had been heavily subdued and the local populations who still rejected Christianity were exterminated.

Pagan Traces in Poland Today

While Old Prussian culture was completely wiped out in the northern crusades (with the exception of a few hags in Gdańsk) many pagan Slavic traditions have managed to stick around, despite Christianisation. As it was with Amerindian culture in South America, the Catholic Church clearly tolerated some aspects of native-culture in order to adapt them into the teachings of the Church and thus assimilate the pagans. All Saints' Day, for example, was previously a day of general ancestor worship and, post-christianisation, the focus was shifted towards prayers for those canonised by the church. Welcoming the start of Summer, Wianki, adapted from the pagan Slavic celebration of Noc Kupały (more recently converted into Noc Świętojańska (St. John's Night) on the Christian calendar) is still celebrated in cities like Kraków and Gdynia. Worship of the dark earth mother Mokosz was conveniently adapted into the miracle of the Black Madonna, redefining the concept of 'the mother' (it was Mary all along!) On another end of the spectrum, the beating and drowning of Marzanna at the turn of winter/spring stuck around, even though the church tried to ban it in the 15th century. I guess it was just too much fun!

In Kraków, there are two man-made mounds, which are dated to the pre-Christian era. The larger one was previously speculated as burial site of King Krakus, the legendary founder of the city, and the smaller one for his daughter Wanda. It's been noted that when standing on the Wanda Mound during the evening of the summer solstice, the sun can be seen setting in a direct line behind Krakus Mound! This astronomical arranged has been compared to similar theories around Stonehenge in the UK, and some archaeologists have therefore speculated that the mounts were created by the ancient Celts, not pagan Slavs.

In Gniezno, the former capital of Poland, excavations on Lech Hill, revealed the presence of a stone mound on which animal bones and ceramics were found, believed to be remnants of sacrifices. It is believed that this place of worship corresponds with an account written by 15th-century Polish Historian Jan Długosz who described a temple built in honour of the god Niya.

Elsewhere in popular culture, Lublin folk-metal band Percival Schuttenbach, most famous for their contributions to the Witcher III: The Wild Hunt game soundtrack, named their first album 'Reakcja Pogańska'.

Comments