Intensity and pleasure are two of the notions that mark the practice of this Zimbabwe-born, Johannesburg-based artist. This is revealed in her choice of subject matter, her processes, as well as the refreshing, playful ways she engages with the public around her work. For her exhibition at the Wits Origins Centre, Brenner invited visitors to think alongside her through a participatory "clay-slamming" workshop – with one of the attendees saying afterward, "I love the idea of art helping us all wrap our heads around when to destroy or abandon and when to keep going." Brenner's work seems primed to elicit profound and personal realisations of this sort.

"Artists need audiences. People make insightful observations and associations, or react in unexpected ways. Watching the film of me repeatedly slamming a globe-shaped ball of clay to the ground, one very young viewer nudged his neighbour and whispered, "She looks so frustrated." It made me think!" – Joni Brenner

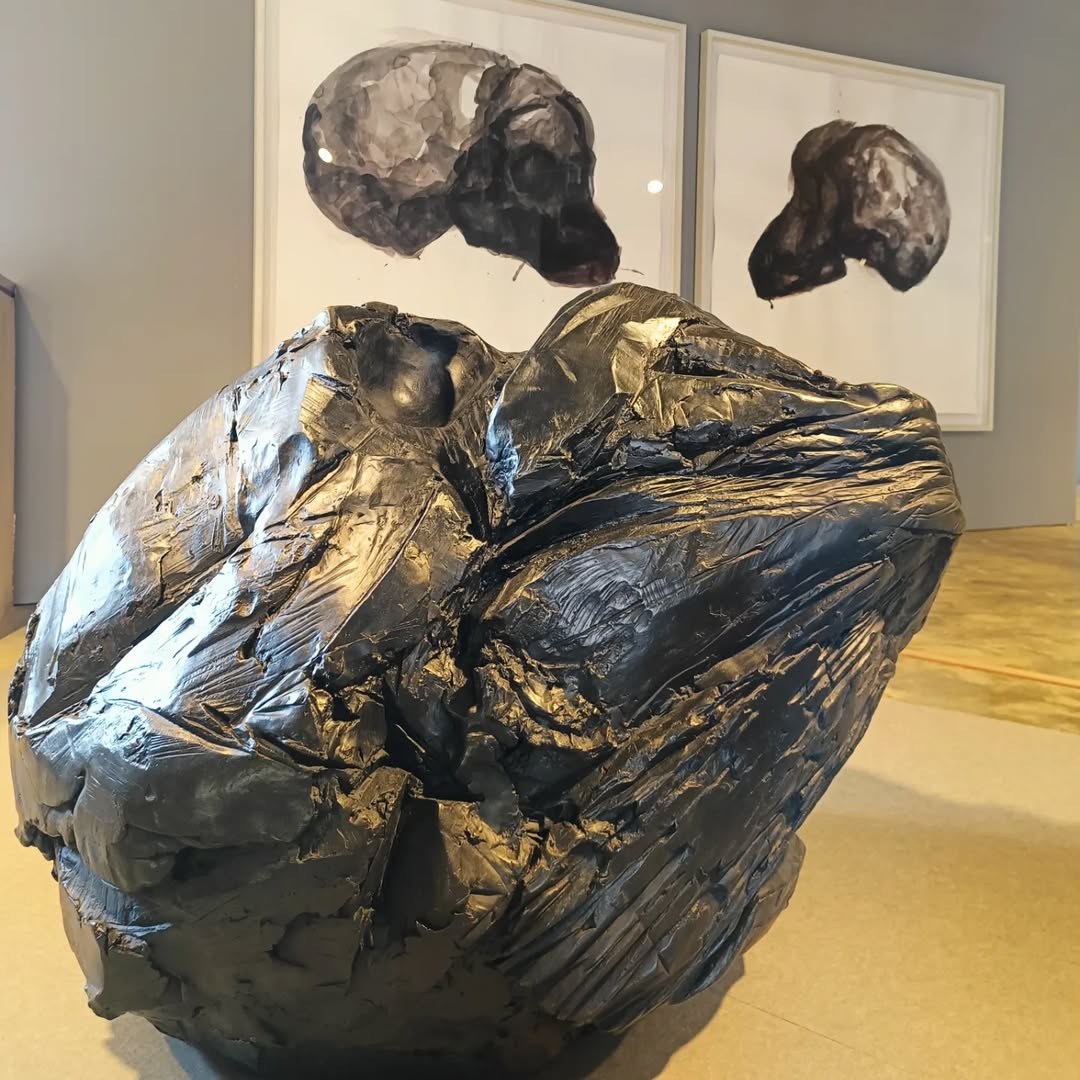

Brenner's first exhibition at Origins Centre was Life of bone: art meets science in 2011, which she co-curated with artist Karel Nel. Impact (until Aug 16, 2025) is her second exhibition with Origins Centre, this time solo, and springs out of her long-term engagement with an impossibly ancient object: the partial skull and jaw of an Australopithecus africanus – an early relative of modern humans – that is estimated to date back 2.5–2.8 million years, known as Taung Child. The name refers to the town in the North West province where this fossil was discovered in a limestone quarry in 1924, but points to something more tender too: the child was believed to be between three and six years old at the time of death.

While a sense of loss is inherent in this discovery, for Brenner it is as much a story of survival, recovery, and "enormous impact". By providing evidence of early hominins on the continent, this fossil is part of what helped shift the focus of human origins research to South Africa – strengthened by subsequent finds at the Wits Sterkfontein Caves and surrounds, in the area today known as the Cradle of Humankind.

Brenner brings a curious, artistic lens to this 'hard' scientific subject, while her treatment of her muse, and the themes the Taung skull evokes, is extraordinarily sensitive and far-reaching. Central to the exhibition is a cast of the skull which shows the recognisable face and left brain endocast, valued for their contributions to our knowledge of human origins, as well as the scientifically featureless right hemisphere – rarely shown in photos, but celebrated by Brenner for its mysterious, crystalline beauty. Her explorations also span watercolours, small raw clay and plaster sculptures made by slamming and squeezing, and a series of bronze skulls that are big enough to sit in.

We took the opportunity to catch up with Brenner to talk about her earliest memories of making, the role of repetition in her practice, and the generosity of Johannesburg art viewers.

What is your first memory of making?

As a child of about five or six I attended art classes in Bulawayo with a woman called Adele Walters. Her living room was the art studio, full of paintbrushes and art horse easels. She would demonstrate techniques, drawing in charcoal directly onto the walls, and use her spit to smudge the lines. I found this shocking and thrilling. I was wide-eyed and in love with Friday afternoons.

When did you realise that you wanted to make a life in art?

I think those early art studio feelings of freedom and risk were powerful and became the kinds of spaces I sought, and where I felt some sense of belonging.

The inspiration for your exhibition at Wits Origins Centre, what is it about the Taung skull that has so captured your imagination?

My work with portraits and skulls demands thought about time passing, about lineage, our place in time, and about continuity. Preparing for an earlier exhibition at Wits Origins Centre Museum in 2011, I wanted to work from a skull much older than a modern human skull, and I asked to visit what is now the Phillip V. Tobias Primate and Hominid Fossil Laboratory at Wits. My compassion for the Taung Child fossil was immediate, I think because it is so small, a child, intact with a full set of milk teeth and perfect brain endocast. One side of the skull has sparkling calcite crystals which formed in the fossilisation process, adding to its precious jewel-like quality.

Although the Taung Child’s skull represents loss and death, it is also a story of survival. That it was fossilised in the first instance is one form of survival; that it remained undisturbed for 2.5-2.8 million years is another. It survived a violent ejection from the cave, was saved from the rubble by quarry workers, and was eventually delivered to Raymond Dart who recognised and described its hybrid ape and human-like features. For me, this story of vulnerability and survival, of loss and continuity, is rooted in hope.

How did your artistic response to this discovery unfold? What has been illuminated for you along the way?

Some of my artistic responses to the Taung Child are recognisable representations – paintings of the skull in watercolour on paper or stone. Though I return to it in this way, I have also used it to explore some of the broader themes it evokes. A young life, swiftly scooped up by a large bird of prey, dropped into a cave and left to die, is a story of loss and destruction. Still, it is also a story of recovery and enormous impact – its description by Dart profoundly changed the way we understand human evolution. In my practice, I constantly confront the question of what must be risked, given up, or destroyed in order to move forward, to find something new, better, more.

We love David Bunn's description of your work as a "visual quarrel" with tradition or art conventions. Tell us how this fits you?

Yes, I love the phrase too – he was referring to my portraiture work which pushes against the usual expectations pinned on portraiture that have to do with idealism and status or aspiration. He may also have been referring to how my approach to portraiture – a genre concerned with life and presence – has always engaged with the co-presence of death or absence. The phrase fits with my take on skulls as reminders of life, kin, and belonging, which runs counter to their conventional association with danger or anything ghoulish.

What strikes you about being an artist working in Joburg right now?

I find I lean into the established wisdom that the most important thing an artist can do is to keep on working with intensity and with pleasure, no matter what. Right now, that means no matter how small the pool of collectors is, no matter how challenging it is to survive as an artist. You weigh up the importance of sales with the (invaluable and possibly more difficult to access) benefits of sharing your work with a critical, engaging, dynamic community of people who show up to look at and take in your work. And in Johannesburg now, I am struck, awed, by how much intellectual capacity and generosity there is among viewers.

Repetition is central to your practice, with you saying "I don't like it when things end. I like it when they keep going." Tell us more.

I always think everything is going to end in a catastrophe, so I suppose my defence or solution is to resist endings at all costs! I do believe though that there is depth of learning and unanticipated joy in the commitment to a practice, where keen observation and attention to what has been done propels the development. I do distinguish between replication – or re-duplication – and repetition.

You've brought your exhibition at Origins Centre to life in various ways, from walkabouts to clay workshops. What do you find rewarding about engaging with the public around your work in this way?

Artists need audiences. People make insightful observations and associations, or react in unexpected ways. Watching the film of me repeatedly slamming a globe-shaped ball of clay to the ground, one very young viewer nudged his neighbour and whispered, "She looks so frustrated." It made me think!

Impact shows at the Wits Origins Centre until Sat, Aug 16, 2025.

Rapid-fire round: Five questions about Joburg

What makes you stay in Joburg?

Although I am ambivalent about nearly everything, I am rooted in a community of friends and colleagues here that is unwavering, and the opposite of ambivalent or tentative.

What is a surprising thing people might learn about Joburg by having a conversation with you?

They might learn more about finding Czech seed beads in Joburg.

If you were Joburg's mayor for one day (average tenure), what would you change?

I’d sort out the Johannesburg Art Gallery and make it a positive and welcoming space for everyone.

What makes someone a Joburger?

Capacity for hope, despite.

Three words that describe the city.

Contrasts, anxiety, innovation.

- ph Briget Grosskopff-1_m.jpg)

Comments