Czesław Miłosz (1911-2004) has come to be regarded as the finest Polish writer of the 20th century, his work influencing generations of natives and foreigners alike. Not only an accomplished poet, prose writer, and essayist, but also a lawyer, diplomat, literary historian, and translator, this exceptional intellectual accumulated more distinctions than you can shake a stick at, including the 1980 Nobel Prize for Literature, the Order of the White Eagle, the title of 'Righteous Among the Nations,' and a Neustadt International Prize for Literature.

Born in what is now Lithuania, Miłosz opted to study law at uni, though the course was to prove a bit of a thorn in his backside – a fear of statistics saw him flunk numerous exams, before finally graduating in 1934. He published his first collection of poetry that same year, and in 1937 took a position at a Vilnius radio station. It was to prove a disastrous union and he was fired for his leftist views. He took another job in radio in Warsaw, though was out of town on holiday when the outbreak of WWII was announced. The next few years saw him lead a transient existence – from escaping the clutches of the Red Army in Lithuania, to seeking refuge in Romania, to working as a janitor in wartime Warsaw, before taking up digs at ul. Krupnicza 22 in Krakow.

The writer’s life then took on a familiar tale of Cold-War-era emigration - he defected west in 1951 after serving as cultural attaché for the Republic of Poland in Paris and then Washington, drawing criticism from both the Polish émigré intelligentsia unhappy with his communist past as well as from the party authorities back home. He won much of the West over, however, with his 1953 anti-Stalinist classic The Captive Mind, and by 1970 he was a US citizen. In the States Miłosz taught Slavic literature at Berkeley and Harvard, composing poetry, philosophical and theological treatises, and essays in his free time. His literary career truly took off with the 1973 release of Selected Poems, in 1978 he received the Neustadt International Prize for Literature and two years later he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, at which point his name was finally taken off the banned list back home. Up until that point in Poland there had not only been a ban on his books, but the mere public mention of his name was forbidden, leading many Poles to be completely unaware of his existence.

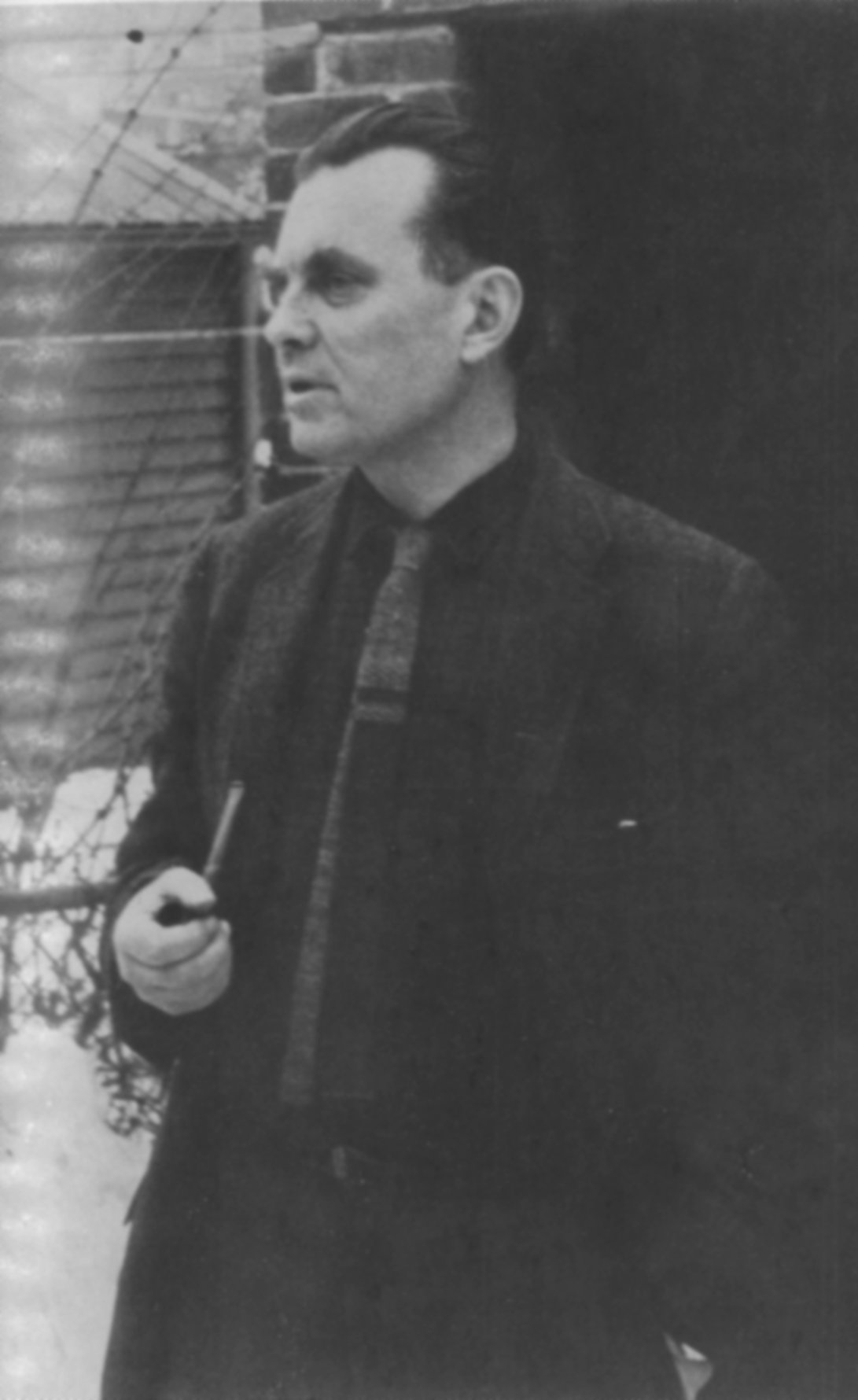

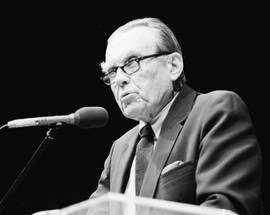

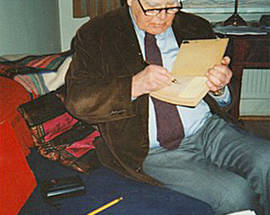

Miłosz in Kraków

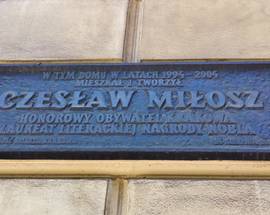

The fall of the Iron Curtain allowed Miłosz the opportunity to move back to Poland, and he did so in 1993, choosing to live in Kraków, the closest substitute for his now-Lithuanian hometown of Vilnius. In fact, the city officially invited Miłosz and provided him with a flat, but amid criticism he insisted on buying his own. Miłosz was named an 'Honorary Citizen of Kraków' (a distinction also granted Mrożek, Szymborska and Lem), and spent the last ten years of his life at ul. Bogusławskiego 6, where a plaque can be seen on the exterior of the building today. The apartment, which remains virtually as the author left it after his passing in 2004, will be made available to the public in the future.

[photo by Anna Kaczmarz / Dziennik Polski / Polska Press]

Miłosz was laid to rest in the Crypt of Distinguished Poles underneath the Skałka Church following his death in his apartment on August 14, 2004 at the age of 93. The writer’s legacy continues to be actively celebrated: 2011 was declared the 'Year of Czesław Miłosz,' and a literary festival dedicated to his memory takes place in Kraków biennially.

Comments