‘Lesser’ we would hardly call it, as Małopolska (‘Lesser Poland’) is perhaps the most well-endowed of Poland’s 16 provinces, harbouring beautiful mountains and national parks (6 of the country’s 23, or 26%), charming medieval towns and UNESCO World Heritage sites (7 of 16, or 44%). When it comes to tourism, most people start their tours of Poland right here with historical Kraków, and might not even make it to the capital Warsaw, choosing instead to visit popular regional Małopolska destinations like Wieliczka, Auschwitz/Oświęcim and Zakopane. As residents of Kraków who have made a (kind of) living out of exploring the region, shining a light on everything from niche museums to obscure castle ruins to random caves, there’s one corner of this bountiful province that we’ve neglected, but really deserves more pop: Gorlice and its surrounding county.

Located in the most south-eastern corner of Małopolska, none can deny that Gorlice is surrounded by beautiful countryside, including the Beskidy Niskie (Low Beskids) range of the Carpathian Mountains and the lovely Klimkówka Reservoir. While the city centre may not be the belle of the ball, it gets a pass for being blown to pieces during WWI (something you Cracovians should keep in mind), while still harbouring its share of curiosities. In fact, when it comes to history, heritage and hardships, Gorlice boasts the type of narrative that's typically glorified in these parts - that of an ancient, multicultural town repeatedly peaking in prosperity and growth at the moment of its destruction by outside forces. Doubly unfair in the aftermath of Gorlice's modern 'golden age' being blasted to ash after only a generation, is that the years since have only engendered misconceptions of the region as unremarkable and unrefined.

Ah, but we’ve been (and learned just how adept the region is at refining, by the way). Although this phoenix is not yet risen, we found plenty of evidence of its potential and enough places of interest to keep any travel snob busy for several days; more than we could include here, in fact. Ideal for a long weekend trip, Gorlice is only 2 hours from Kraków (100km), and 1 hour from Tarnów (40km). If you’re looking for an offbeat destination dripping with natural beauty, rich in history and ripe for discovery, Gorlice really has much to offer. Rent a car and get rolling.

Get Started in Gorlice’s Old Town & Market Square

Where else? While today it’s a bit unfair to compare Gorlice’s Old Town to others oozing charm across Małopolska, if it weren’t for WWI we’d be doing so with no problem. Founded way back in 1354 during the reign of King Kazimierz the Great, Gorlice has plenty of history and particularly prospered as a centre of the arts and trade during the Renaissance period. Uniquely built upon a hillside overlooking not one, but two rivers, it’s easy to imagine that Gorlice would be a pearl of southern Poland were it not for the heavy bombardment it suffered during WWI. With all but 40 of the town’s buildings reduced to ruin in 1915, today Gorlice’s market square lacks the awe-inspiring architecture one might hope for, but still harbours a few handsome townhouses, an imposing Town Hall and neo-Renaissance Lesser Basilica tucked, as you’d expect, into one corner.

[photo by Marcin Gugulski, courtesy of Gorlice UM]

In terms of design, Gorlice’s Rynek (market square) is unique from any other we’ve seen. With a tree-lined one-way street dividing it down the centre, and descending downhill at a strong angle, the market square has two halves and each half has two levels. Granted, it’s not a great look to have a street going through the middle of your market square, but from an engineering and architectural standpoint, the Rynek is quite interesting, and the design affords for some intriguing features, including a pedestrian bridge with a porthole over the road on the side of the Town Hall, and the modern Gorlice City History Pavilion built subterraneously into the sidewall on the north side. The primary function of the Pavilion - a multi-use facility for concerts, exhibits and other events - is as a tourist information centre, so make it your first stop when you arrive.

A few other buildings of note near the market square include the Karwacjan Manor House (Dwór Karwacjan) - the partially reconstructed defensive manor house originally built by the city’s founders in the early 1400s. Located one block north of the Basilica on ul. Wróblewskiego, the Manor is certainly one of Gorlice’s most beautiful buildings and open to the public today as a museum and art gallery.

One block south of the market square on ul. Wąska is the Gorlice Regional Museum (Muzeum Regionalnego PTTK w Gorlicach) - a small museum with modest, but strong exhibits about the Battle of Gorlice and the oil industry, while next door is Dark Pub - arguably the town’s best restaurant and bar. Also seek out the beautiful Kromer High School at ul. Marcina Kromera 1 - a major success story in the effort to restore some of Gorlice’s historical buildings to their former glory.

‘Thar’s Black Gold in Them Hills!’

Experience Gorlice’s Oil Industry Heritage

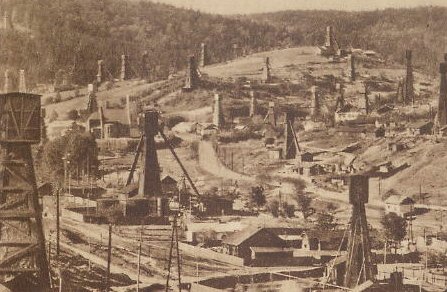

Hardly visible today and sadly unbeknownst to many, Gorlice was a centre of the Galician oil industry, which brought incredible prosperity to the region in the half-century before World War I. The area’s inherent historical connection with crude oil can be seen in the Polish language itself, where the word for ‘oil’ comes directly from the name of the river that flows through the Gorlice valley - Ropa.Primarily used for the conservation of leather and wood, and later as a lubricant for machinery, in early days locals would collect crude oil where it seeped out of the ground and sell small quantities in the markets along Europe’s trade routes. As techniques for extracting larger quantities developed, and distillation increased its usefulness, value and demand, mining for ‘black gold’ became a proud, but dangerous vocation for many locals. Beginning in the second half of the 19th century the Galician oil rush was on, and wooden drilling towers and oil wells soon dotted the land from Gorlice in the west to Borysław and Drohobycz in the east, where the largest deposits were later found (today in Ukraine). Galicia was the largest producer of crude oil on the continent.

Although the region’s oil deposits dwindled in the 20th century and have more or less dried up, their legacy has not disappeared. The Carpathian-Galician Oil Trail - part of a larger cross-border tourist trail that leads from Gorlice to Lwów/Lviv - connects points of interest and preserves the history of the oil industry immediately around Gorlice.

Claim to Flame: Łukasiewicz & The First Kerosene Streetlamp

Gorlice PTTK Regional Museum.

Evidently now too big for the lowlights of Lwów, Łukasiewicz split from Zeh and took his talents to Gorlice in late 1853, where he continued his work from a pharmacy located on the ground floor of the Town Hall. Promoting his distilled kerosene as a lighting source, Łukasiewicz saw to it that the first kerosene street lamp was soon installed in Gorlice’s Zawodzie district in 1854. At the same time, he was getting deep into the business side of petroleum. The same year that Gorlice’s landmark streetlamp was ignited, Łukasiewicz opened the world’s first oil mine in Bóbrka - about 50km to the east, and in 1856 he opened the world’s first industrial oil refinery near Jasło (30km east of Gorlice). All the while he was based in Gorlice, where he opened more mines, started a Polish journal about the petroleum industry and initiated the creation of the National Oil Association, with its headquarters in Gorlice, naturally.

Though he left the town in 1858, Łukasiewicz’s legacy still looms large in Gorlice, which has dubbed itself ‘Miasto Światła’ - The City of Light - in honour of his accomplishments. At the exact spot where the world’s first kerosene streetlamp was lit, today stands a 16th century shrine outfitted with a lamp, and a commemorative mural honouring Łukasiewicz’s achievements; nearby is a bust of Łukasiewicz. Outside the Town Hall is a more prominent monument of Łukasiewicz and his influential invention in the form of a bronze bench, above which you can see a replica of Gorlice's first streetlamp, recessed into the wall of the building.

For more about Ignacy Łukasiewicz and Gorlice’s oil industry heritage, visit the PTTK Regional Museum, where you’ll see Łuka memorabilia, a collection of kerosene lamps - including a prototype of the first kerosene lamp, oil industry models, machinery and more.

"This liquid is the future wealth of the country, it's the wellbeing and prosperity of its inhabitants, it's a new source of income for the poor, and a new branch of industry which shall bear plentiful fruit."

Sadly, Łukasiewicz couldn’t see the future, and though he had the second part right, he was incorrect about the longevity of Gorlice’s local wealth.

Get Blown Away by the Battle of Gorlice

If Gorlice was so rich, where’s the grandeur today? Despite the evidence buried literally all around, few realise that Gorlice was entirely razed to rubble during WWI (not WWII, as most Polish historical narratives go). Perhaps this is due to a lack of glamorised attention given to the war’s Eastern Front, compounded by the less-than-snappy, and slightly inaccurate name the battle is remembered by in English - ‘The Gorlice-Tarnów Offensive.’ Whatever the case, the fact remains: Gorlice was a picturesque and prosperous town before the Great War. Afterwards it was a smoking ruin that was never rebuilt to its former glory.

What happened? In short, the Russian Army steam-rolled across Galicia - then a part of Austro-Hungary - headed for Kraków. They took Gorlice on November 15th, 1914, but the Austrians pushed back, retaking it in early December, only to lose it again right after Christmas. The two sides basically came to an impasse at this very spot, and dug in. Gorlice’s residents lived on the frontlines of trench warfare for almost six months, exposed to crippling hunger, cold and poverty as the most wealthy residents evacuated the town. In April the Central Powers decided they wanted the Russians out of Galicia and began amassing troops and armaments along 30km of the Eastern Front from Ciężkowice to Ropica Górna via Łużna and Gorlice, intent on breaking through the Russian positions along this line in order to eventually retake Lwów.

The advantage of the German and Austro-Hungarian armies over the Russians was not just manpower (an almost 3:1 advantage), but firepower (5:1), and they used the element of surprise. Artillery bombardments began striking Russian-occupied Gorlice on May 1, making it rather clear that the leaders of the Central Powers were willing to sacrifice the town to achieve their aim. On May 2nd the German infantry charged in amidst increased mortar fire, capturing Gorlice by the afternoon as the Russians set fire to the town in retreat. The plan was a success and the Central Powers kept the offensive going, steadily driving the Russians backwards out of Galicia until they retook Lwów on June 22nd. Considered a major victory for the Central Powers, the human cost of the Battle of Gorlice (May 2-5, 1915) is estimated at about 20,000 soldiers. It’s material cost was not only the old city of Gorlice, which lay in total blazing ruin after being hit by 44,000 mortars, but also the Galician oil industry, which would basically have to be rebuilt after the war.

For a more visceral experience, you might consider visiting Gorlice during Majówka, when celebrations and reenactments of the battle occupy the city’s full attention each year on May 2nd.

Pay Your Respects to the Glorious Dead...and their Grave Designers

With so many casualties to bury, the Austro-Hungarian Ministry of War in Vienna set up a special Department of War Graves dedicated exclusively to this task. Their directive was to not only give the dead proper burials, but to also create immortal monuments of artistic merit that would honour the heroism and sacrifice of the fallen. To this end, architects, artists, carpenters, sculptors and gardeners were employed, while Russian and Italian POWs were forced to do most of the labour, which began in 1916. The decision was made to not discriminate between armies, nations or rank, resulting in the same modest sepulchral treatment given to officers and privates, to Austrians, Germans, Russians, Hungarians, Czechs, Slovaks, Italians, Ukrainians and Poles - often buried side-by-side. Additionally, it was decided to bury the dead more or less on the battlefields where they fell, resulting in a stunning 378 WWI cemeteries from the Eastern Front across Western Galicia.At the very heart of the 'Trail of Military Cemeteries from the First World War,' 86 of these graveyards are located in the region of Gorlice, with 6 in Gorlice proper (numbers 87, 88, 90-92, 98). Each of these places is unique in size, shape and design, and their presence upon seemingly every hilltop makes them difficult to avoid, whether you are seeking them out or not. There are two particular cemeteries, however, that distinguish themselves for their beauty and artistry, making them worth a visit.

The second cemetery of note is WWI Eastern Front Cemetery No. 123 in Łużna, just 15mins north of Gorlice by car. Located on Pustki Hill - one of the key strategic positions during the Battle of Gorlice - this necropolis is one of the largest and most diverse in the region. Designed by Slovakian architect Dusan Jurkovic, the cemetery features a truly odd wooden chapel which looks a bit like a rocketship (to us anyway), and beautiful views of the valley below. With 1,204 total soldiers from three armies, the cemetery was granted the European Heritage Label in 2016 - one of only four sites with that distinction in Poland - for its ecumenical message of fraternity and equality between the men laid to rest here, who represent many different ethnicities, religions and nationalities from contemporary Europe.

Get Into the Great Outdoors

Gorlice is a great jumping-off point for exploring the Low Beskids (Beskidy Niskie) - a picturesque and very accessible sub-range of the Carpathian Mountains. Full of natural beauty, wildlife and recreational opportunities, anyone interested in hiking, cycling, kayaking or horseback riding will find ample opportunities in peaceful spaces not yet overrun by tourists.

One such place is Klimkówka Lagoon, located just 20km south of Gorlice (20-25mins by car). Created by damming a section of the Ropa River in 1994, the 310 hectare lake still serves a practical function, but also a recreational one. Equipped with beaches, water equipment rentals, camping and house rentals, enthusiasts of a wide variety of activities - including fishing, swimming, sunbathing, windsurfing, kitesurfing, sailing and kayaking - come here in the summer season to relax. What actually makes the reservoir most enjoyable, however, is simply the picturesque views of the landscape.

[photo courtesy of Gorlice UM]

But you don’t even have to leave Gorlice to immerse yourself in nature. The city boasts one of Poland’s oldest, wildest and most beautiful parks, ideally situated at the fork of the Ropa and Sękowa rivers. Covering 24 hectares, Gorlice City Park was established in 1900 by its namesake Wojciech Biechoński. While a lower section nearer the river features playgrounds, a restaurant and cafe, the upper reaches upon Park Hill (Góra Parkowa) are covered with the Sokolski Woods - a great place to get lost in the wild and admire 150 year-old trees.

Wander Onto the Wooden Architecture Trail

While you’re out in the countryside around Gorlice, you won’t be able to ignore the numerous signs for Małopolska’s Wooden Architecture Trail, which features some 255 timber structures of historical and cultural significance. The most famous of these are the eight wooden churches inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List, of which five are located within 25km of Gorlice - namely in Binarowa, Sękowa (less than a 10min drive from Gorlice’s market square), Owczary (only a further 10mins from Sękowa), Kwiatoń and Brunary Wyżne. The unique Greek Orthodox churches of Owczary, Kwiatoń and Brunary Wyżne are of particular significance and value for their ties to the Lemkos - a distinct ethnic group that proliferated in Galicia before being forcibly resettled after WWII.

_m.jpg)

_m.jpg)

Comments