Setting the Stage

Silesia has been at the geographic and political crossroads of Europe throughout its entire history - a position which has seen it sitting ambivalently on the borderlands of this or that kingdom, or continually placed in the crosshairs of various land-grabbing empires and nations throughout history. Going back to the Middle Ages, the region was first recorded in the history books as a Piast duchy in the late 13th century and was part of the Kingdom of Poland before King Kazimierz the Great conscientiously spurned it; Silesia then slipped under the Bohemian Crown in the 14th century, who passed it like a kidney stone to the Habsburgs in the 16th century before Frederick the Great took a liking to it and had a little mid-18th century war over the matter until it was in his Prussian domain. By that time Silesia had passed hands more than any other territory in Europe, and, as such, developed a distinctly unique and diverse cultural make-up of Polish, German, Bohemian, Austrian and Jewish influences, including its own Silesian dialect of the Polish language (though some argue it has its own distinct language). By the time modern nations were being formed across Europe in the wake of Napoleon, Silesia couldn’t be legitimately claimed as the byrights homeland of any particular nation (though it remained within German borders).

Silesia’s true political relevance didn’t begin to take shape until the 19th century when the revelation spread that the region was rich in natural resources, particularly coal, and it developed into a hotbed of heavy industry which would largely enable the German war machine during World War I. When the Allies agreed to the reconstitution of the Polish nation in the aftermath of the war, Silesia became a bone of contention between the two countries where the local population was an almost even split between Germans and Poles.

In drafting the Treaty of Versailles, the Allies sought to inflict territorial losses on Germany and lands east of the Oder River, particularly Upper Silesia which had a Polish ethnic majority, were a natural choice. When the Allied intention appeared in initial drafts of the treaty, the potential loss of Upper Silesia sent shockwaves through Germany; widespread unrest and even famine were predicted and the Germans found an audience with their claim that the country’s war reparations would be impossible to repay without the resource-rich region creating revenue for the Rhineland. After loud German protest, it was finally decided in 1918 that the territorial matter would be decided democratically when a mandated plebiscite took place in two years time; until then, German administration and police would be left in place in the region. The decision deeply disappointed Warsaw which had expected the Silesian territories with a Polish majority east of the Oder River would be incorporated into the new Polish Republic without debate, and angered the regional Polish community eager to escape discrimination in Germany.

Vote for Poland and you will be free.

With the political situation in Silesia extremely precarious, it’s curious what the Allies expected to happen in those two years before the plebiscite, if not a lot of bickering turning to bloodshed. In fact, the unrest that the Allies sought to avoid by delaying a decision was already in place, exacerbated by Allied inaction. Thanks to ‘Germanisation’ in the decades before WWI and anti-Polish legislation during it, tensions between Silesian Germans and Poles had been high since well before the armistice and conflict seemed inevitable. Both sides had formed citizen militias: German war veterans created ‘Freikorps’ (Free Corps) specifically to terrorise Polish activists, most of whom were engaged in their own Warsaw-supported conspiratorial organization, 'Polska Organizacja Wojskowa' or 'POW' (Polish Military Organisation) – a precursor to Polish intelligence. In addition to the tough guy tactics, nationalist propaganda and rhetoric were prolific on both sides. With the reconstitution of Poland – a country which hadn’t been on the map for 123 years – Polish nationalism was at an all time high, spurred locally by the impassioned speeches of Wojciech Korfanty who encouraged Silesian Poles to unite and seize control of the region in order to ensure it would be incorporated into the Second Polish Republic.

The First & Second Silesian Uprisings

Tensions finally broke on August 15th, 1919 when rogue German border guards murdered ten civilians in the Mysłowice coal mine. Polish armed insurrectionists took several small towns in the region and opened guerrilla warfare in the countryside against the Weimar Republic Provisional National Army as Polish miners across Silesia went on strike. The uprising was short-lived however, as the German Army quickly summoned a force of 61,000 troops and easily broke the back of the uprising within ten days. In response to the horrible reprisals that followed - as some 2,500 Silesian Poles were rounded up and either hanged or executed by firing squad – in February 1920 an Allied Plebiscite Commission composed of Italians, Frenchmen and Brits was sent to Upper Silesia to try to keep the peace. It was soon apparent however that the strength of the coalition was not enough to establish order, a problem aggravated by divided sympathies amongst the Allies between the two sides.

While the First Uprising had been largely spontaneous and reactionary (and ineffective), a second, slightly better organised uprising was staged one year later on August 19th when most industrial cities in the region were quickly captured by insurgents or paralysed by strikes. Polish insurgents were able to seize control of government buildings in the districts of Katowice, Pszczyna and Bytom, and fighting spread throughout the region before being slowly brought to an end through Allied military involvement and diplomatic success in getting the two sides to negotiate terms of a ceasefire. The Polish side succeeded is dissolving the regional police force and creating a new one which would be 50% Polish, as well as gaining admission into local administrative positions; in return the dissolution of the Polish Military Organisation was guaranteed, although this never actually took place as the Poles slyly continued with their secret intelligence operations. As you do.

The Third Silesian Uprising

During negotiations over the fast-approaching fixed date of the dubious plebiscite to be held March 20th, 1921, the Polish side lobbied hard to restrict voting to Silesian residents only. However, the near-sighted western powers didn’t see it that way and made anyone over 20 who was born in Silesia eligible to vote in the plebiscite. The result was an influx of some 200,000 Germans from outside the region taking place in the crucial vote, which - when it finally occurred – was questioned by the Allies and deemed to be largely inconclusive, though that’s not what the numbers said. The results which sat before them officially revealed 59.4% in favour of Silesia remaining in Germany, and only 40.5% for joining the new Polish Republic. Berlin was claiming it had won the whole of Silesia, Warsaw was crying foul, and the Allies seemed confused or perhaps forgetful as to why they held the plebiscite in the first place. The conversation returned to what to do with the crucial ‘Black Triangle’ of important industrial cities east of the Oder – Katowice, Bytom and Gliwice. The French remained preoccupied with weakening their aggressive neighbour and unflaggingly supported Silesia’s incorporation into Poland; the Brits and Italians remained recalcitrant about reparations. Day 1,000 of the debate was sounding a lot like Day 1.

Though the Allies continued their wheel-spinning spat over the fate of the region, rumours spread that the pro-German position would soon prevail and the Poles prepared for what they perceived would be their last chance to seize control of the region and force its incorporation into the Polish Republic. To the fore came Wojciech Korfanty, a politician turned revolutionary, well-known for his defence of Germany’s Polish minorities and inspiring rhetoric. Able to quickly organise a volunteer army of 40,000, Korfanty initiated the Third Silesian Uprising on May 2nd, 1921 with the strategic destruction of rail bridges, which essentially severed all connections between Silesia and Germany, thus thwarting the potential assistance of the German government to the local Freiburg paramilitary units his men were now pitched against (all official military troops had been removed from Silesia by that time). Korfanty’s surprise offensive pushed the small German forces he faced westward and by June 4th he had crossed the Oder River and captured the strategic 400 metre-high hill of Annaberg from which he could apparently dominate the entire Oder Valley.

As the Germans spent the next two weeks preparing a counter-offensive, Korfanty’s insurgents essentially seized all of Upper Silesia and had things well enough in hand to gain some diplomatic leverage with the Allied Commission. The Germans would eventually engage Korfanty’s men in The Battle of Annaberg - the only proper engagement during the Silesian Uprisings, which had up to that point featured mostly skirmishes and positional guerrilla battles – and what ensued was a crude battle of epic inconclusiveness (a running theme through this story) lasting several days with large numbers of senseless losses on both sides. The Allied Commission meanwhile made a few speeches condemning the Uprising, but generally did little to curb the violence. In fact in-fighting within the Commission actually led to the active prevention of Allied troops getting involved in the conflict to benefit one side or the other.

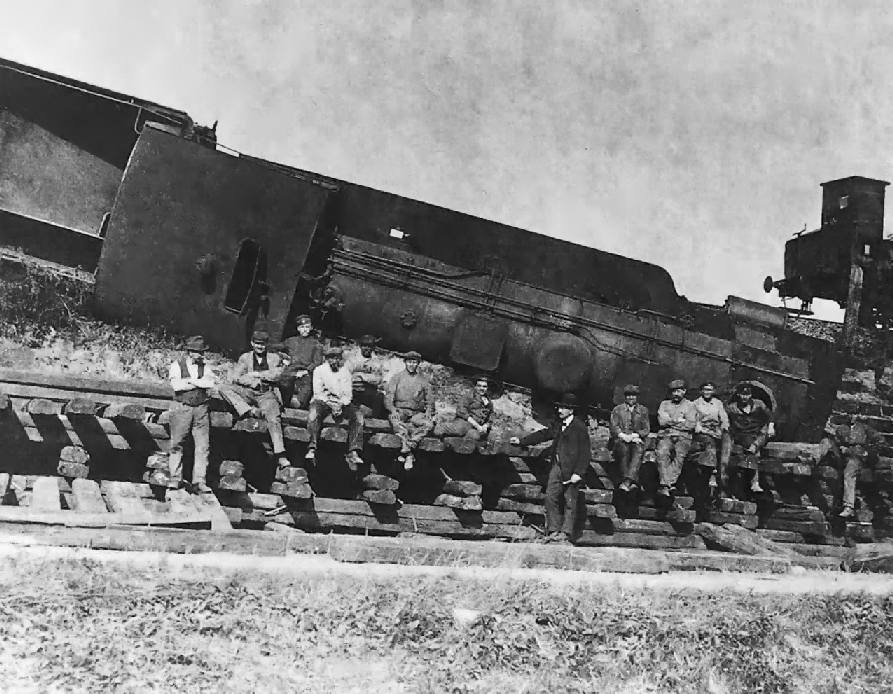

[Some incredible faces in here. How many of these lads are even 18?]

That Korfanty thought his uprising was sustainable is highly doubtful. Taking the opportunity for diplomacy while he was still in a position of strength, Korfanty offered to withdraw his men behind a demarcation line on the condition that the released territory be occupied by Allied troops only, not Germans. Essentially Korfanty’s strategy forced the Allies to enter the conflict at a time when his uprising could be perceived as a success, the Allies agreed to Korfanty’s proposal and the move was later given credit for earning a more favourable Polish result when national boundaries were finally drawn. On July 1st British troops finally began the advance into Upper Silesia that would produce a general amnesty and withdrawal of all the weary combatants who foolishly expected some sort of decision regarding the territory to have already been made while they were doing all of that killing and dying. None was forthcoming. Finally the Allied Commission could agree on only one solution: pass the decision on to the council of the League Of Nations. To continue the comic diplomacy, the League Of Nations then handed the matter over to an investigative committee of four representatives, one each from the apparently much more decisive countries of Belgium, Brazil, China and Spain. Gathering their own data and conducting their own interviews with Germans and Poles from Upper Silesia, in October 1921 – after a mere six week investigation - the crack committee came down with a decision. It was their determination that the territory should basically be split down the middle following ethnic lines as much as possible. The earth shook, stars exploded, an angel grew its wings…and Katowice became part of Poland.

At the final tally, Poland had actually obtained less than a third of the geographic territory, but it was generally considered to be 'the good part.' Of 61 coal mines, 50 fell to PL; of the 37 furnaces, 22 to PL; of the 16 zinc and lead mines, 12 went to Poland along with all the iron mines, and on and on. Germany had lost the war and to Poland went the spoils. In addition to Katowice, the main towns of Chorzów and Tarnowskie Góry were also incorporated into Poland, all three of which had very small to negligible German minorities. Although today it may not seem like such a great outcome to the underwhelmed tourist walking around downtown Katowice, the Silesian Uprisings were considered a major success for Poland and are today an extreme point of pride for Silesians.

Comments