Conditions continued to worsen, however, and in April 1940, Hans Frank – Nazi commander of the ‘General Government’ (the part of German-occupied PL that was not directly incorporated into Germany) – ordered the resettlement of Kraków’s Jews, in keeping with his desire for the capital of the General Government to be a “Jew-free city.” As a result of resettlement in late 1940, Kraków’s Jewish population was reduced to the 16,000 deemed necessary to maintain the economy at the time, with the 52,000-odd others forcibly deported, largely to labour camps in the east.

Establishment of the Kraków Ghetto

'Like a nestless bird carrying fear on its wings,

I walk my wife and children through the deluge of tears,

expelled from paradise into an alien world,

not knowing what sin have I committed.'

-translated excerpt from Miałem Kiedyś Dom (I Once Had a Home), by Mordechaj Gebirtig, May 1941

On March 3rd, 1941 Otto Wächter, Governor of the Kraków district, decreed the establishment of a new ‘Jewish Housing District’ on the right bank of the Wisła River in the district of Podgórze. What would become known as the ‘Kraków’ or ‘Podgórze Ghetto’ initially comprised an approximately 20 hectare (50 acre) space of some 320 mostly one- and two-story buildings in Podgórze’s historic centre bound by the river to the north, the Krzemionki hills to the south, the Kraków-Płaszów rail line to the east, and Podgórze’s market square to the west.

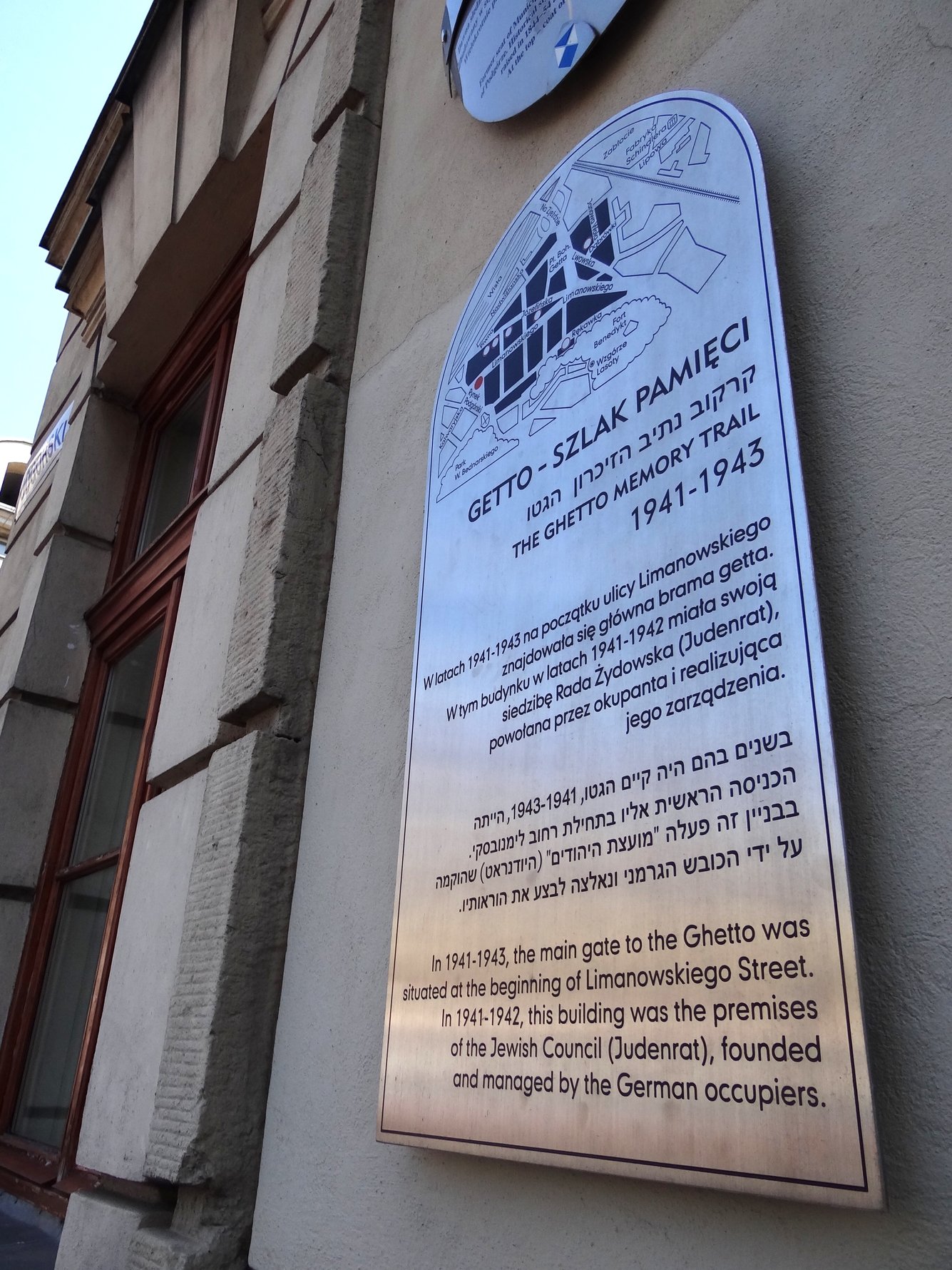

Overcrowding was an obvious problem with one apartment allocated for every four families and an average of two square metres of living space per person. Windows facing ‘Aryan’ Podgórze were bricked or boarded up to prevent contact with the outside world and a 3 metre high wall was erected around the confines of the ghetto, crowned with arches conscientiously designed to resemble Jewish tombstones. Four guarded entrance gates accessed the ghetto – the main gate from Rynek Podgórski on ul. Limanowskiego, another on the east end of ul. Limanowskiego near its intersection with ul. Rękawka and ul. Lwowska, a third close by at the intersection of ul. Lwowska and ul. Józefińska, and another at Plac Zgody (today known as Plac Bohaterów Getta). A tram initially ran through the ghetto, and though it made no stops, food and other valuable commodities frequently found their way into the ghetto via its windows.

Many Jewish institutions were transferred into the ghetto, and several non-Jewish businesses continued to operate, most notably Tadeusz Pankiewicz’s Eagle Pharmacy on Plac Zgody. Many Jews also worked outside the ghetto, particularly in the Zabłocie industrial district, which included Oskar Schindler’s enamelware factory at ul. Lipowa 4.

Deportations

Following an October 15th, 1941 decree requiring all Jews of the Kraków region – not just the city centre – to move to the Podgórze Ghetto, a further 6,000 Jews from villages around Małopolska entered the ghetto, making conditions unbearable. To alleviate the distress Nazi authorities happily announced that they would begin deportations, and 1000 people - mostly elderly and unemployed –were loaded into cattle cars and sent to Kielce, where they were expected to find aid from local Jewish authorities. Not knowing what else to do, many of them actually returned clandestinely to their families in the Kraków Ghetto.

Following the Wannsee Conference in January 1942, the Nazis began to initiate ‘The Final Solution’ – Hitler’s systematic plan for the annihilation of European Jewry. May 29th, 1942 was the first of ten days of terror within the Kraków Ghetto as it was surrounded by Nazi troops and all documents were inspected. Those who couldn’t produce proper work permits were assembled on Plac Zgody before being transferred to Płaszów rail station, loaded into cattle cars in groups of 120, and sent to Bełżec death camp in eastern PL. Unsatisfied by the initial numbers, the Germans continued their arbitrary round-ups for days.

On June 6th, all previous documents were declared invalid and ghetto occupants were required to apply for a new ‘Blauschein’ or Blue Pass; those that were denied likewise met their deaths in Bełżec, including popular poet and songwriter Mordechaj Gebirtig and renowned painter Abraham Neuman. By the end of the action, 7,000 Jews had been sent to their deaths, and many more simply shot in the streets. [The June deportations were one of the best documented of such actions, however photos from the events are still commonly misidentified as having been taken during the ghetto's liquidation in March 1943.]

Two weeks later the area of the ghetto was reduced almost by half to the north side of ul. Limanowskiego and demarcated by barbed wire. The increased density of the population and increasing brutality of the Germans set off a wave of suicides. Though some remained optimistic, worse was to come. Work was also beginning on the nearby KL Płaszów labour camp, which would eventually portend the end of the Jewish ghetto in Kraków.

Liquidation of the Kraków Ghetto

As soon as enough barracks had been built, Goeth ordered that the inhabitants of Ghetto A permanently relocate to Płaszów, and on March 13th, 1943 local SS Commander Julian Scherner ordered the final liquidation of the Kraków Ghetto. Carried out in two phases, at least 6,000 Jews (some sources cite up to 8,000) from Ghetto A were immediately transported to Płaszów; all children under 14 and any other remaining Ghetto A residents were ordered to assemble on Plac Zgody the next day with the residents of Ghetto B. Despite likely knowing what lay in store, many mothers stayed behind when Ghetto A was liquidated, refusing to abandon their children.

March 14th, 1943 was likely the bloodiest day in Podgórze’s history. The ghetto - which at that point essentially consisted of only Plac Zgody and the block of buildings just south of it – was surrounded by German troops who attempted to herd its residents to the transports leaving from the square. Chaos reigned and those who resisted or attempted to escape were shot. Over 1,000 people were killed in the streets (some estimates are as high as 2,000) and the 3,000 that left via cattle car went almost directly to the gas chambers in Auschwitz. After this final deportation, the Germans cleaned up their mess, looting the houses, stripping the luggage strewn everywhere of anything valuable, and taking down all the barbed wire. The Kraków Ghetto disappeared leaving almost as little trace as the Jews who lived there.

Exploring the Former Jewish Ghetto in Kraków Today

The most simple and logical route for tourists to explore the former ghetto is from the Bernatek Footbridge, down ul. Józefińska, to Plac Bohaterów Getta ('Ghetto Heroes Square,' formerly Plac Zgody). Keep your eyes peeled for tombstone-shaped informational plaques mounted on some of the buildings as you head down ul. Józefińska. Plac Bohaterów Getta is home to the famous Eagle Pharmacy, today a museum dedicated exclusively to witness accounts of life in the Kraków Ghetto. If you're invested in this subject, this small museum is a must-visit, as is reading Tadeusz Pankiwecz's excellent memoir, The Kraków Ghetto Pharmacy, which can be bought from the museum gift shop, or online here. From Plac Bohaterów Getta you are only a short walk from Schindler's Factory, but also from the two surviving fragments of the original ghetto wall - the second of which, behind the public middle school on ul. Limanowskiego, is partcularly striking and worth the trip.

Below we list all the points of interest within the territory of the former Jewish Ghetto, all of which are easily within walking distance of each other. Follow the links for more info, including GPS.

Comments