The history of Jews in Poznań dates back to the city's first days, though - like so many places in Central Europe - this rich heritage was all but extinguished with the horrors that followed Hitler’s rise to power. Today its traces are dim, but also plain to see if you know how and where to look. Read on for a full account of Poznań's Jewish history, or scroll to the end for a list of present-day Jewish heritage sites.

A Brief History of Jewish Life in Poznań

Although their first recorded mention dates to 1364, Jews were present in Poznań before the city was even officially established, including some in the courts of the early Piast dynasty rulers. A 13th-century decree of protection by Prince Bolesław the Pious drew more Jewish settlers, and when the city of Poznań was staked out in 1253, Jews were assigned its northern section, with the area between today's Wroniecka, Szewska, Stawna and Mokra streets becoming the heart of the Jewish District. As Poznań grew and prospered, so too did it's Jewish population, which was the largest in Poland throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance. At the start of the 15th century it’s estimated that one in four buildings on ulica Sukiennicza - the de facto centre of the Jewish community - were occupied by Jews, a fact not lost on city planners who later renamed it ‘ulica Żydowska,’ or ‘Jewish Street.'

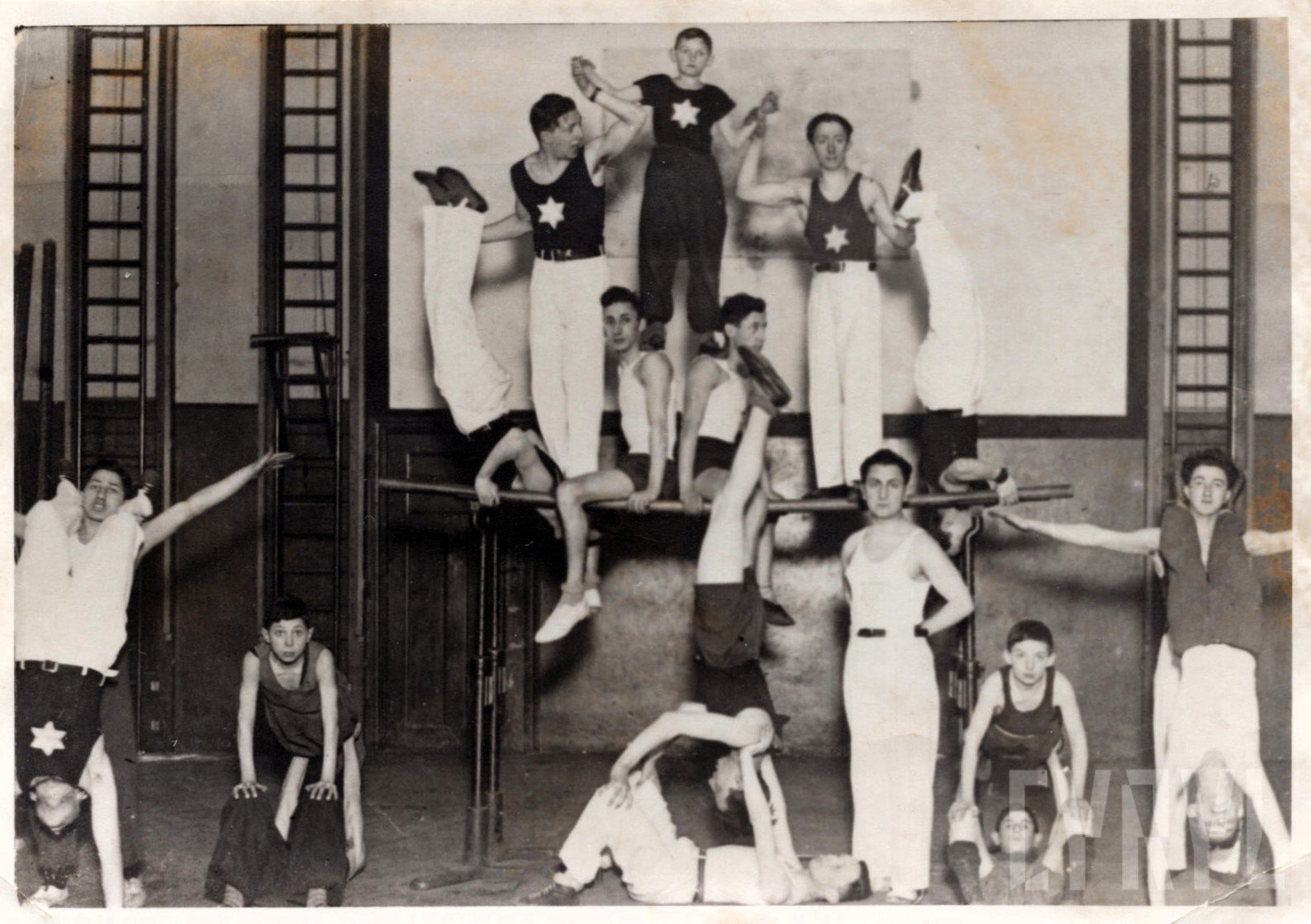

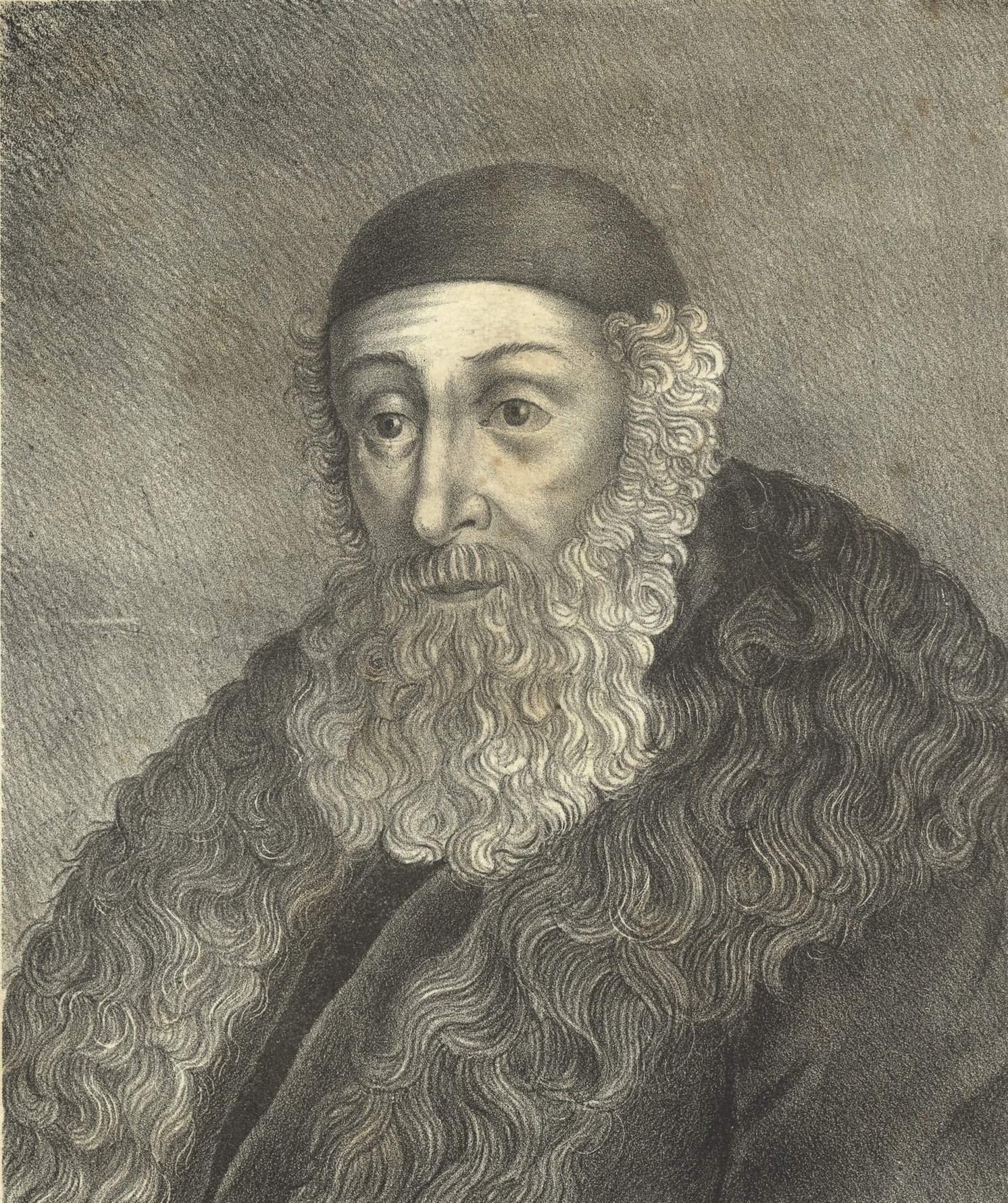

The Poznań rabbinate was one of the most important in Poland, with rabbis who held this post either previously serving, or going on to assume, important rabbinical responsibilities in other large communities such as Kraków, Lublin and Lwów (L'viv). Famously, Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel - born in Poznań in 1524 - went on to become Chief Rabbi of Prague, where legend claims he created the Prague Golem, before returning to Poz late in life to be Poland's top rabbi. Polish-Jewish relations were not without their tensions, however, with blood libel accusations and suspicious arsons a regular occurrence. These tensions peaked in 1736 when Rabbi Aryeh Leib ben Yossef was accused of using Christian blood for ritual purposes, and publicly burned at the stake. Rabbi Akiva Eger fared better in the 19th century, becoming of Poland's most famous and respected rabbis when the community was perhaps at its peak.

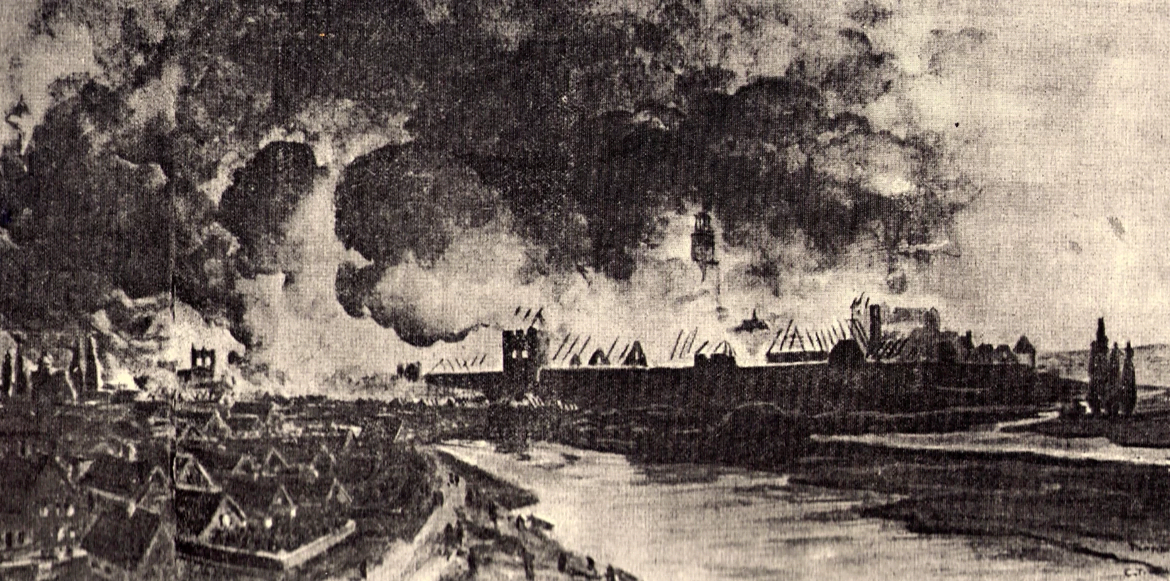

Poznań’s Jewish District was characterised by narrow alleyways and densely packed with overpopulated wooden dwellings, making it vulnerable to (often suspicious) fires. The worst of many conflagrations was the Great Fire of 1803, which started in and entirely consumed the neighbourhood, going on to burn down half of Poznań's buildings, and leave over 7200 people homeless. With the Jewish District devastated, Poznań's new Prussian authorities essentially liquidated it and allowed Jews to settle more freely throughout the city. A series of reforms - although gradual - also removed many of the political and civil restrictions on Jews, resulting in their full and equal rights as Prussian citizens by the mid-18th century. These changes led to a great strengthening of bonds between Poznań’s German and Jewish communities, and the latter began embracing German culture and language. At the start of the 20th century, both communities also built extravagant new symbols of their strength and prosperity.

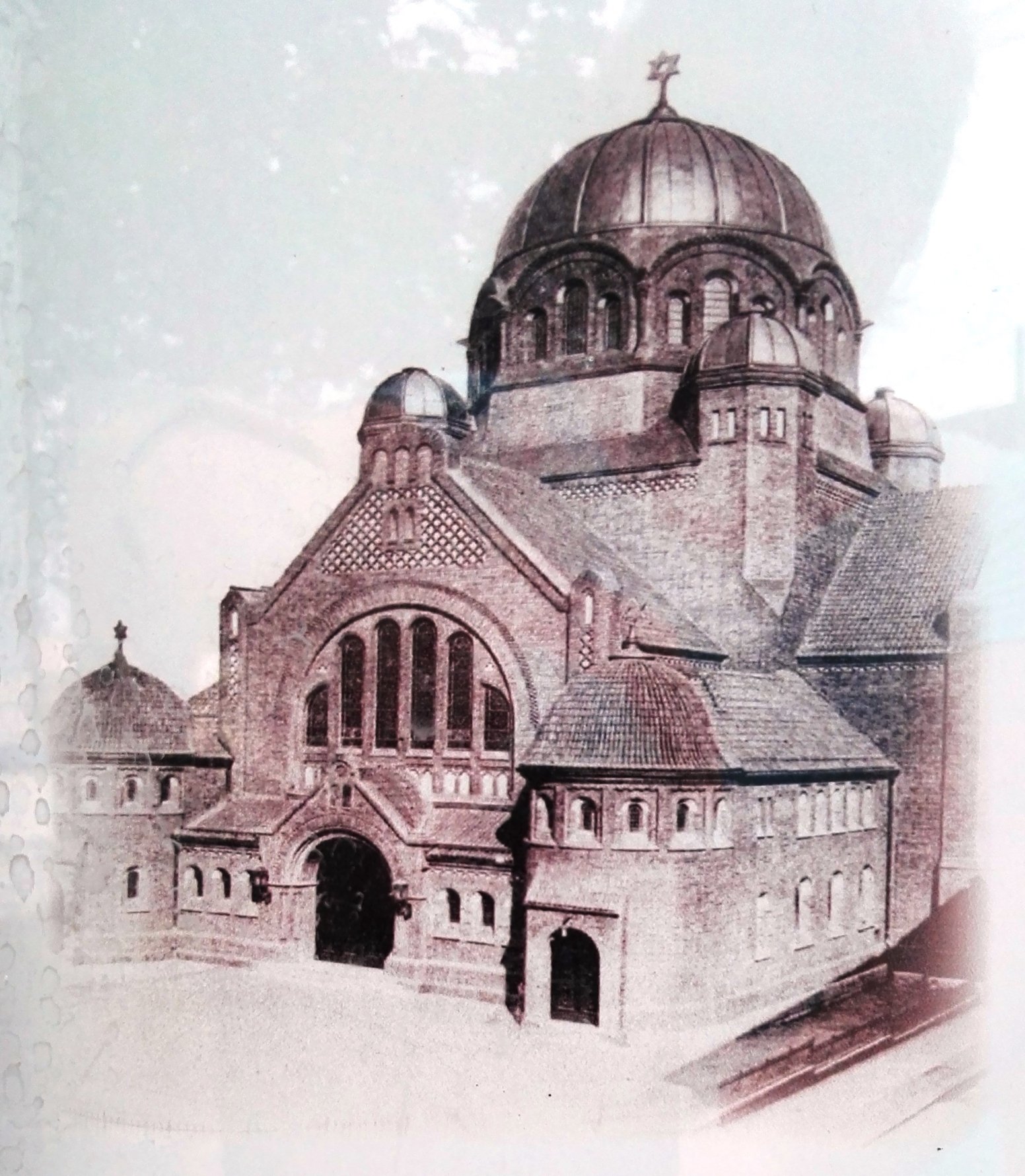

The fortunes of Poznań’s Jewish community peaked in the early 20th century with the building of the grand 'New Synagogue,' replacing a complex of 16th-18th-century synagogues on Żydowska Street, which were subsequently demolished. Designed by Berlin architects Cremer & Wolfenstein, the monumental Neo-Romanesque red brick structure held 1200 worshipers, and featured a richly decorated interior, numerous copulas and a copper-plated dome. It was completed in 1907 - a few years before the Imperial Castle, which was under construction simultaneously; both were symbolic of Prussian prosperity, cost millions to build and became the dominating landmarks of their respective ends of town.

After WWI

Ironically, Poznań had one of the smallest Jewish communities in Poland at the outbreak of World War II - only 1500-3000 people, or less than 1% of its population (most major Polish cities were 25-35% Jewish at that time). Due to their assimilation under Prussian rule, Poznań’s Jews didn’t support the Poles in the Wielkopolska Uprising, and when the city became Polish (and Catholic) again in 1919, they once again found themselves on the hard end of local feelings. A vast majority of Poznań's Jews emigrated west to Germany after WWI, expecting greater tolerance there.As we know, such tolerance evaporated under the German Nazi regime, which invaded Poland and occupied Poznań in September 1939. The city was named capital of the Reichsgau Wartheland province, and a sinister plan was hatched to rid Poznań of its Jews within three months (rather than creating a closed Jewish Ghetto in Poznań - the pattern followed in many of Poland's other major cities). Deportations began as soon as December 11th, 1939, with Jews packed into cattle trucks bound for the ghettos of Warsaw or Lublin, and on April 15, 1940, the fascist rag Ostdeutscher Beobachter gleefully reported the removal of the Star of David from the last synagogue left standing. Those who remained in the ghettos of Reichsgau Wartheland, as well as some poor souls from Austria, Luxembourg, and other countries - around 11,000 people total - were brought into the city’s 29 labour camps to do back-breaking work, including building the Poznań airport and a highway connecting Berlin and Łódź (using Jewish tombstones as some of the building materials), digging what is now Lake Rusałka and Lake Malta, and liquidating Jewish cemeteries. Meanwhile, horrific medical experiments were conducted on inmates at the ‘Reich University’ Institute of Anatomy, with some corpses shipped off to the Natural Museum in Vienna to become part of an anti-Semitic exhibition. The labour camps operated until August 1943, at which point prisoners were sent off to the Auschwitz death camp.

Indeed, Poznań was something of a model Nazi city, and on October 4, 1943, Heinrich Himmler gave a sordid speech to his Nazi cronies about the extermination of the Jewish people inside the city's Town Hall. A small number of Jews survived WWII in hiding, and several hundred actually returned to re-settle in the city after the war. However no effort was made by the government to re-establish Jewish culture, and the subsequent anti-Zionist policies of the post-war communist government saw the number of Jews dwindle to well under a hundred. Today a very small community is active, with their headquarters located near the remains of the 'New' Synagogue at ul. Stawna 10.

_____

Discover the best of Poznań OFFLINE with our regularly updated guidebook.

-----

What to See | Jewish Heritage Sites in Poznań Today

The Nazis were meticulous in their destruction of Jewish heritage and traces of it are sadly few and far between today. In fact, one of the most visible Jewish-related sites on Żydowska Street these days is actually a testament to the vicious anti-Semitism that plagued the city for much of its history. One of Poznan’s most offensive, harmful and well-documented legends (recorded in multiple sources, including by esteemed medieval historian Jan Długosz) claims that, in 1399, local Jews paid a poor woman to steal three Christian sacramental wafers, placed them on a table and began stabbing them with a knife. As the story goes, blood burst everywhere, so the Jews tried to drown them in a well, but they just floated out, hovering in the air. The Jews then wrapped them up and tried to bury them in the marshes south of the Old Town, but the holy hosts unburied themselves and floated there too, scaring the Jews into fleeing the scene. Later, a young shepherd found the floating wafers, a church was consecrated on the spot of their discovery, and the offending Jews were burned at the stake.

That's the founding myth of Poznań’s Corpus Christi Church, and it was passed down the generations with enough conviction that when a hidden table and well were uncovered in the basement of the tenement building at ul. Żydowska 34 in 1620, it was designated as the site of the infamous sacrilege and soon became a pilgrimage site. Under intense sustained pressure from the Carmelites, the city finally allowed for the entire townhouse to be converted into the Church of the Most Holy Blood of Jesus in 1704, and believers still go there every Sunday to pray and drink the water of the well, which they say has miraculous properties (something about a blind girl's vision being restored during the stabbing was tacked on later). Dare to venture inside the church today and you’ll still see 18th-century frescos depicting a trio of Jews desecrating the wafers with the aid of the Devil himself. This infamous example of anti-Semitism is told in detail on the church's website without any hesitation, and the frescos remain in plain sight (and were refreshed not long ago), while most other traces of Poznań’s Jewish heritage have vanished from view. To be fair, an antique plaque referring to the profanation of the hosts, which long adorned the church’s facade, was finally taken down by the archbishop in 2005 (you can see it in the Archdiocese Museum).

Elsewhere on Żydowska Street, keep an eye out for the former Salomon Beniamin Latz Home for the Elderly and Infirm at ul. Żydowska 15/18. These addresses were the centre of Jewish religious life in Poznań for several centuries, and the site of three separate synagogues until 1908. In a poor state at the beginning of the 20th century, the Jewish community organised a property swap with the Latz Foundation in order to build their grand 'New' Synagogue on the site of the Latz Foundation's Jewish Hospital; in turn, the Latz Foundation moved their operation here to the site of the dilapidated and now obsolete synagogues, which were demolished to make way for the current building.

Latz was a Poznań merchant who donated a large part of his fortune to the poor in 1829, and his Foundation was one of Pozńan's most eminent Jewish institutions. The current building was built as a modern healthcare centre and home for the elderly in 1909, and included an in-house synagogue (beth midrash) on the lower two floors. Later it served primarily as an old folks home (rather than hospital), and after the war it was converted into apartments. If you somehow manage to get into the residential building today, traces of the in-house synagogue’s balcony can still be seen in the stairwell.

Rather miraculously, Poznań's 'New' Synagogue survived the war by being converted into a swimming pool and rehabilitation centre for Wehrmacht officers. The 'Swimagogue' (as it has unfortunately been called locally) was returned to the Jewish community in 2002, however numerous plans for its restoration or conversion into a museum have proven unrealistic over the years. Defying belief, in 2019 the Jewish community sold the property to a developer, and plans for its conversion into an apartment complex have been approved by city authorities. Its current slide into ruin seems to be a last sad step before it is gutted and turned into high-rent housing.

In 2008 the square outside the synagogue was named in honour of Rabbi Akiva Eger (1761-1837), the renowned Talmudic scholar and halakhic decisor who served as Poznań's head rabbi for 23 years until his death. Regarded as the city's greatest rabbi, he lead a congregation that was the second largest in Prussia at the time, but his influence and status were known acorss Europoe. Today his name is synonymous with Talmudic genius, and his works are still studied by scholars. Eger was buried in the 19th-century Jewish cemetery on ul. Głogowska, which was destroyed under Nazi rule, and its headstones were used to pave roads during World War II. After the war, the site of the former cemetery was incorporated into the Poznań International Fairgrounds, wiping away almost all trace of its existence. In 2008, however, a small memorial site at ul. Głogowska 26A, which consists of the reconstructed graves of Rabbi Akiva Eger, his wife and son, and two other Poznań rabbis, was created on the only undeveloped part of the former cemetery grounds. Unfortunately, the site is inside the gate of a residential building (alongside the trash bins), and official visits are by previous arrangement through the Jewish community only (email gekafka@jewish.org.pl); you can peek through the gate anytime, however, and may even have success finagling your way inside if you're stubborn.

In lieu of any other surviving Jewish cemetery in Poznań, Jewish headstones (matzevahs) recovered from various city streets in the post-war years have been placed in a lapidarium at the Miłostowo Cemetery (ul. Gnieźnieńska) alongside mass graves holding the remains of around 1000 Holocaust victims. Elsewhere, a memorial to the inmates of one of Poznań’s Nazi labour camps stands near Edmund Szyc Stadium at what is now Righteous Among the Nations Square (ul. Królowej Jadwigi 51). Museums exploring the horrors of forced labour and the extermination of Jews during World War II include the Wielkopolska Martyrs Museum - located in Fort VII (a former death camp) 5km west of the centre, and the Martyrs Museum in Żabikowo - 10km south of the centre.

Comments