Located in the Carpathian Mountains, in the southeastern corner of Poland, the Podkarpackie (Subcarpathian) voivodeship is a region of great natural beauty and a unique melting pot of cultures, offering visitors scenic landscapes, outdoor activities, cultural treasures and colourful folk traditions. For centuries Slavic ethnic groups like the Lemkos, Boykos, Pogorzans, Dolinians and others thrived in this historical borderland, contributing to the region’s rich multicultural tapestry.

Despite postwar efforts to homogenise Polish society, there are many places in southern Podkarpackie (and southeastern Małopolska) where these ethnic cultures have been preserved and can still be experienced. Below we detail the region’s most prominent ethnic minorities and where their heritage can be explored today; but first, some essential history explaining how these ethnic groups came so close to extinction in the area.

Operation Vistula & the Displacement of Podkarpackie’s Ethnic Populations

Although distinct in their craftsmanship, cuisine, music, dress and other customs, Podkarpackie’s ethnic minorities all suffered a similar 20th-century fate that has greatly diminished their presence in the province today. Following 123 years under Austro-Hungarian rule, Podkarpackie found itself at a geopolitical crossroads in the wake of World War I as Polish, Slovakian, Ukrainian and even Lemko national movements all vied for territory and sovereignty. Eventually, of course, the territory we today know as Podkarpackie became part of the Second Polish Republic, and the renewed Polish state began efforts to assimilate these ethnic groups - most of which were of Greek Catholic or Orthodox faith - into Polish Catholic society.

When the borders changed again after World War II, and neighbouring territories became part of Soviet Ukraine, Polish and Soviet authorities used alleged support for the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (a paramilitary group fighting for a free Ukraine) as justification for the expulsion of hundreds of thousands of people from both sides of the border. This included the forced relocation of entire ethnic populations from Podkarpackie to the formerly-German territories now in western Poland in 1947. Known as ‘Operation Vistula’ (Akcja Wisła) the controversial campaign succeeded in ending hostilities, but also resulted in accusations of ethnic cleansing. A very small percentage of those who were exiled did eventually return decades later, providing a vital lifeline to the region’s ethnic folk traditions and ensuring their preservation.

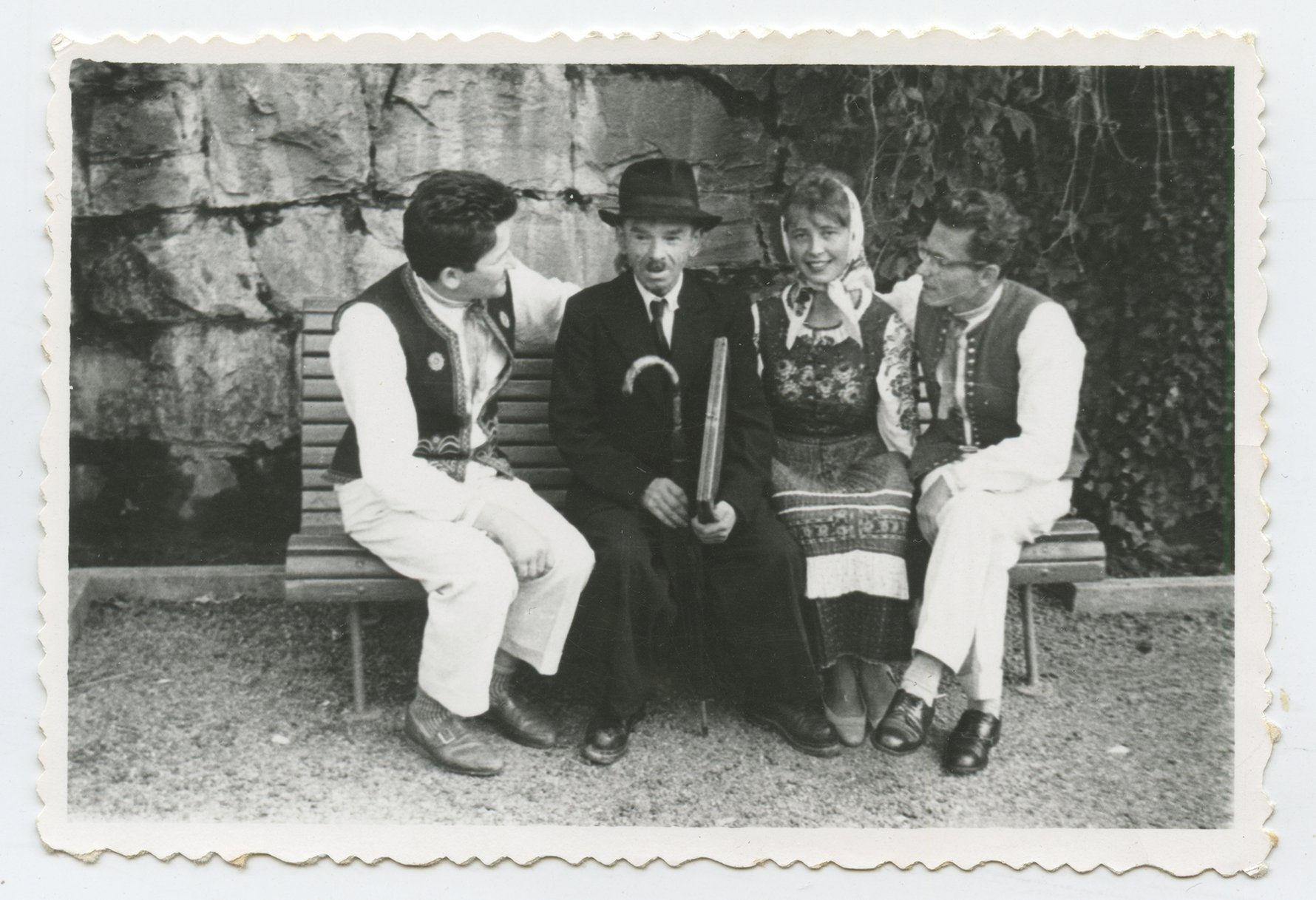

ETHNIC CULTURES OF PODKARPACKIE

The Lemkos

Forging their unique identity and culture over many centuries, the Lemkos (Łemkowie) are a Carpathian sub-ethnic group who probably settled in the areas of southeastern Poland around the 16th century, busying themselves with animal husbandry, farming, woodworking and masonry. Podkarpackie was inhabited by Lemkos for over four centuries before these communities were forcibly removed from their lands after World War II. Despite this, traces of their vibrant heritage and cultural influence can still be seen and felt across the region, particularly at their surviving homesteads and places of worship.

Lemko identity is rooted in their religion (predominantly Eastern Orthodox), unique language (variably described as its own Slavic language, or a dialect blurring Ukrainian, Slovakian and Polish) and cultural traditions, which are slowly being revived throughout Podkarpackie, but also Upper Silesia - the region of Poland with the next-highest Lemko population (a result of postwar resettlements). The Lemko language is increasingly taught in Polish schools, and the number of people declaring Lemko nationality is on the rise; some estimates put the number of ethnic Lemkos in Poland today as high as 60,000. In Poland, the prolific Lemko artist Nikifor is well-known for his naive paintings and drawings of Krynica-Zdrój, its Catholic and Orthodox churches, and Carpathian landscapes. People of Lemko descent who have achieved international renown include jazz pianist Bill Evans, comic book artist and Spider-Man co-creator Steve Ditko, and pop artist Andy Warhol (birth name Andrew Warhola).

Lemko Heritage Sites

The Museum of Lemko Culture in Zyndranowa is an open-air ethnographic museum (skansen) where you can see Lemko homesteads from the 1800s and easily imagine how this communities lived before World War I. Similarly, the Museum of Folk Architecture in Sanok features a small reconstructed Lemko village; the Orthodox church complex at its centre - relocated from Ropki - is one of the most valuable objects of sacred wooden architecture in Poland, and arguably the highlight of the entire museum.

Well-preserved traditional wooden Lemko churches can also be visited throughout Małopolska, Podkarpackie and western Ukraine, with several of them inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List, including the Orthodox churches in Turzańsk, Powroźnik (Małopolska), Owczary (Małopolska), Kwiatoń (Małopolska) and Brunary (Małopolska). Other excellent examples can be seen in Czyrna, Komancza, Hańczowa and Zdynia, to name but a few.

Holy Mount Jawor, on the Polish-Slovakian border near the village of Wysowa-Zdrój, is an important Lemko pilgrimage site, considered sacred by Orthodox believers. It was here that repeated apparitions of Mary of Nazareth were reported in the 1920s, and a spring alleged to have healing properties sprang up at the site, attracting more pilgrims during the interwar period. A wooden Greek Catholic church was erected at the site of the apparitions in 1929, which is on the north side of the peak. Pilgrims often leave large Orthodox crosses on the hill around the spring and church, adding to its mystique.

The Boykos

The Boykos (Bojkowie) are a Ruthenian ethnographic group descended from East Slavic tribes, who lived across a wide area of the Carpathian Mountains from Wysoki Dział in the Bieszczady Mountains (in the west) to the Łomnica Valley in Gorgany, Ukraine (in the east) for 500 years. That included a significant community in Podkarpackie until the forced resettlements carried out by the government during 'Operation Vistula' in 1947. Boykos share the same religious affiliation as the Lemkos (mostly the Ukrainian Greek Catholic or Orthodox Church), and also speak a dialect of the Rusyn language, but one distinct from their Lemko neighbours. Their dress, folk architecture and customs also differ from the Lemkos, and their population numbers today are also much more diminutive by comparison (not reaching 500 people in any country). The Ukrainian poet, writer and statesman Ivan Franko is likely history's most well-known Boyko descendent.

Boyko Heritage Sites

A hardy people who once led herds of livestock through mountain pastures filled with wildflowers, today Boyko culture is being rediscovered. Traces of old huts, churches, cemeteries and other evidence of settlements - some of it taken over by nature long ago - can be found in some of Podkarpackie's most rugged and romantic territory. For a more in-depth view of Boyko history and culture, a visit to the Boyko Culture Museum in Myczków is highly recommended. The exhibits include many photographs, agricultural artefacts, domestic items, embroidery, traditional folk attire and more, and the basement includes a gallery of handicrafts and a cafe where you can drink traditional Boyko-style coffee.

The Museum of Folk Architecture in Sanok also features a traditional Boyko village composed of six wooden structures relocated from around the region, including distinctive Boyko churches from Rosolin and Grąziowa.

The Boyko were master carpenters and the unique craftsmanship and architecture of their wooden Orthodox churches can be seen at the examples in Czerteż (near Sanok) and Smolnik. The value of the church in Smolnik was enough to get it inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List and while you’re there, you can also visit the ‘Bieszczadzka Koza’ goat farm in the same village to see how locals are still adapting traditional ways today.

Lastly, the Icon Worskhop in Cisna is a unique place where you can admire and even purchase beautiful Orthodox icons painted by owner and master artist Jadwiga Denisiuk, direct from the artist’s studio. Icons painted by Denisiuk decorate the walls not only here, but also in the Vatican, the office of the Polish Prime Minister and various churches in the area.

The Pogorzans

The Pogorzans (Pogórzanie), also known as Polish Uplanders, are an ethnic group of Poles living in the Beskid Ranges of Podka

rpackie and Małopolska. Their unique community developed due to a cultural mix of Polish and German settlers, the former arriving in the 10th-13th centuries and the latter, smaller group brought in during the 14th century to curb the influx of the neighbouring Ruthenians, who also had an influence on the Pogorzans. In contrast to other ethnic groups of the region, the Pogorzans speak a dialect of the Polish language and practice Roman Catholicism. Due to historical differences in construction methods, interior design, dress and economy, Pogorzans are typically divided into two groups - Western and Eastern - with the conventional border between them being the Jasiołka and Wisłoka rivers.

Traditionally the Pogorzans have been weavers and farmers, raising livestock and crops like flax, rye, wheat, oats and barley, but they were also instrumental in the development of the oil industry in the 19th century. In 1854, the world's first oil mine was established in Bóbrka, near Krosno, and Pogorzan territory became the cradle of the early oil industry, vastly altering their lifestyle, economic and living standards, and also causing the disappearance of many folk traditions. With the decline of the local oil industry, many Pogorzans today work in the agritourism and hospitality sectors.

Pogorzan Heritage Sites

The Museum of Folk Architecture in Sanok - a vast 38-hectare open-air ethnographic museum (skansen) preserving the region’s pre-war wooden architecture, artefacts and daily traditions - features areas dedicated to all of Podkarpackie’s ethnic groups, but none of them larger than the Pogorzans. The museum divides this group into Western and Eastern Pogorzans, with 9 objects in the former and 16 in the later, plus a section devoted to the late-19th century oil boom that greatly affected the region’s Pogorzan communities. Similarly, the Pogorzan Village Open-air Museum in Szymbark (Małopolska) also preserves old rural architecture. With 15 objects over 2ha, this smaller ethnographic park near Gorlice is exclusively dedicated to the Pogorzans.

Incredible examples of historical wooden churches associated with the Pogorzans can be seen in Haczów, Sękowa (Małopolska) and Binarowa (Małopolska) - all three of which are inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

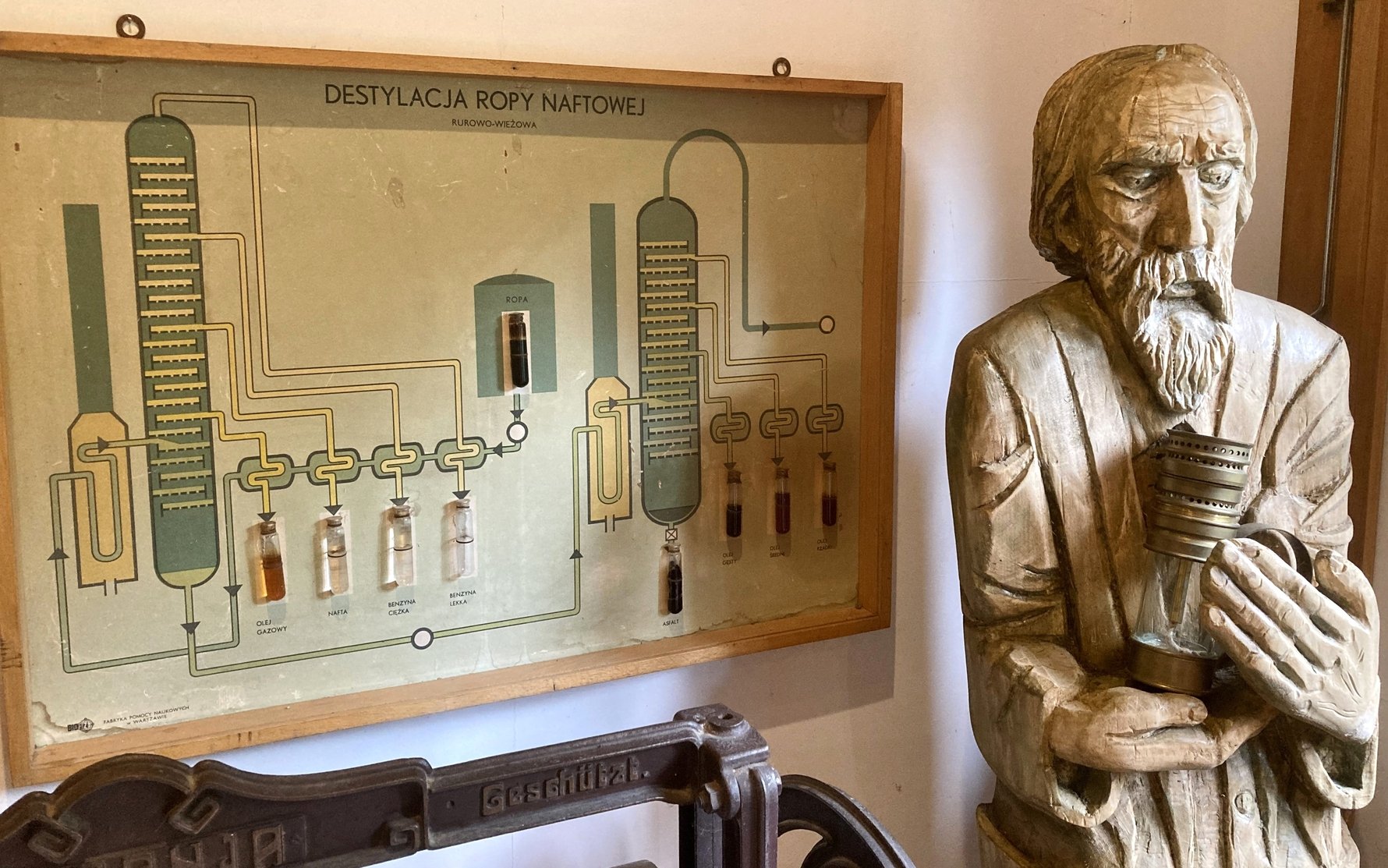

There are also many sites in eastern Małopolska and eastern Podkarpackie related to the early oil industry, which particularly affected the communities of the Western Pogorzans. Foremost among them is the Museum of the Oil & Gas Industry in Bóbrka, located on the site of the world’s oldest still-operating oil mine, founded by Ignacy Łukasiewicz (inventor of the kerosene lamp) in 1872. Located on 20-hectares and surrounded by forest, at the museum you’ll see two 19th century oil wells, and countless artefacts from those early days of petroleum. Further west near Gorlice (Małopolska), you’ll also find similar museums on a smaller scale at the ‘Magdalena’ Open-air Museum of the Oil Industry, and the Museum of Oil & Ethnography in Libusza.

The Dolinians

One of the lesser-known ethnic groups from Podkarpackie are the Dolinians (Dolinianie). Researchers explain that this could be due to the proximity of their settlements to larger cities, resulting in their urbanisation by 1939. Another factor is that many historical records and cultural artefacts of their communities were lost during and after World War II. Thanks to the determination of ethnographers, however, a clearer picture of this enigmatic group has emerged in recent years.

The Dolinians were descendants of the 14th and 15th century Poles, Germans and Ruthenians who settled in the fertile San River valley. The intermingling of these three societies over generations led to a unique new fusion of cultural traditions, rituals and beliefs. Their faith was linked to both the Roman and Greek Catholic churches, and they spoke a regional Polish dialect.

The name 'Dolinianie' indicates that they were valley-dwellers, with their villages primarily located along rivers. As a result they excelled at cultivating cereal crops, potatoes and turnips in the rich soil. Their cuisine has always been rich in vegetables which they sold at urban markets. They also raised cows, pigs, horses, chickens etc. for their own domestic use. Unique rituals of the Dolinians involved baptisms where the child was dressed in the feathers of the eiderdown from the mother’s wedding night, and brides going from door to door of those villagers who were not invited to the wedding ceremony to ask for their blessing and forgiveness!

Dolinian Heritage Sites

Once again, the fabulous Museum of Folk Architecture in Sanok offers perhaps the best window into the lost world of the Dolinians, with 11 historical structures relocated there to recreate a pre-WWII Dolinian village, including a wooden fire station from Lipinki from 1934.

The hillside Monastery of Discalced Carmelites in Zagórz is also associated with the Dolinians. Although in ruins today, the monastery can be visited and offers fine views of the surrounding countryside and Osława River valley below. Next door is the Foresterium Culture Centre which presents the history of the site using virtual reality and other interactive displays.

Comments