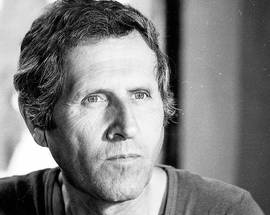

On the occasion of the 100th birth anniversary, see the exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art from April 11 to May 12: Julije Knifer - from the collections of the Museum of Contemporary Art

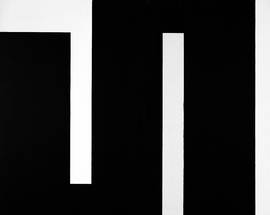

Croatian artist Julije Knifer (1924-2004) spent the best part of 45 years painting endless variations on the theme of the meander, a snaking abstract form almost always rendered in stark black and white.

The Osijek-born, Zagreb-educated artist became obsessed with the meander motif in his late thirties and spent the rest of his life exploring its possibilities, as if on a quest to discover a form that would express everything that he wanted to say about painting, life, the universe and everything. As Knifer himself explained (in one of the many artist’s statements scattered throughout the exhibition), “in the space of a few months I arrived at what you might call the end… at the meander, a point beyond which you quite simply cannot go.”

Ana Knifer, the artist’s daughter, recently recalled in print that when she asked her father what the meander meant, he answered simply ‘it is life’. In many ways he was seeking to channel the same energies as Russian suprematist Kazimir Malevich, who famously unleashed his epoch-defining Black Square on the St Petersburg public in 1915.

Knifer’s meander became one of the defining symbols of Zagreb’s famously avant-garde art scene from the Sixties onwards. He was always somewhere near the heart of the action, co-founding the Gorgona anti-art group in 1959, and exhibiting in the ground-breaking series of New Tendencies exhibitions that, from the early Sixties onwards, turned the Croatian capital into a centre for constructivist art, op-art, and computer art.

Despite such iconic status Knifer never made a great deal of money from his art, at least not to begin with. He spent the most productive, middle part of his career living in a small flat in the Črnomerec district, looking after his daughter during the daytime and painting meander pictures on the kitchen table at night. By the 1980s Parisian galleries were enthusiastically promoting Knifer’s work, and these French contacts enabled Knifer to move first to Nice, then Paris, where he lived from 1994 until his death.

It was Parisian painter Francois Morletti who described Knifer as the man who ‘paints radiators’, an image that’s hard to shake out of your mind once you’ve seen some of his larger canvases. That Knifer is more than just a radiator man is, however, the main message of this exhibition. Indeed such is the variety of meander shapes on display that one can’t help admiring Knifer’s single-minded search for the perfect set of curves. Pencil drawings on sheets of A4 paper, taken from different periods throughout his career, show the artist working his way through all possible permutations of the meander, rarely failing to come up with results that were both beautifully decorative and coolly meditative at the same time. A display case filled with his worn-down pencils serves as a reminder that many of his later large-scale pictures consisted of dense layers of pencil shading rather than paint, producing surfaces that were louder, thicker, blacker than anything that could have been achieved with acrylics.

There is engrossing film of the 1975 peformance Arbeitsprozess, when Knifer hung a 30-metre-high canvas from the cliff wall of a quarry just outside Tübingen. It makes strangely hypnotic viewing; the painting flapping in the breeze like the logo of some new corporate religion.

One genuine revelation comes from Knifer’s diaries, their daily entries written up in the form of interlocking meanders, each in a different-coloured felt-tipped pen.

Comments