A Brief History of Jews in Romania

The story of the Jews in Romania is not a happy one. Relatively small until the mid-19th century, the size of the Romanian Jewish community - predominantly urban - grew from the 1840s onwards as large numbers of Jews sought refuge in Moldavia and Wallachia from persecution in Tsarist Russia, and by the mid-1860s there were more than 150,000 Jews nationwide. Alas the Jews fared little better - initially - in Romanian lands than they had in Russia, with strict laws enacted preventing them from wearing traditional dress, sending their children to school and even becoming Romanian citizens. There were frequent attacks on Jews and their property (particularly in Iasi) while there was a major anti-Jewish riot in Bucharest in 1866, when large numbers of Jews were beaten and the Choral Temple (rebuilt soon afterwards) desecrated and destroyed.

There was another wave of Jewish immigration in 1903-5 following the Chisinau Pogrom of April 1903 (Chisinau was at the time part of the Russian Empire), and while the plight of the Jews improved considerably as their numbers and political influence grew, it was only in the aftermath of World War I that Romanian Jews were awarded full civil rights, later guaranteed in the 1923 Romanian Constitution. It was during the 1920s that the number of Jews living in Romania reached its peak (at around 730,000), around a third of whom lived in Bessarabia (today the Republic of Moldova). Bucharest’s Jewish population peaked at around 70,000 in 1930: as much as ten per cent of the city’s population.

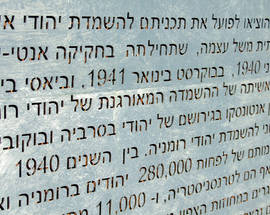

Romania was not, however, immune to the anti-Semitism of 1930s Europe, and the rise in popularity of the fascist scum Legionnaire Movement and its horrific paramilitary wing, the Iron Guard, can in part be explained by its violently anti-Semitic policies. By the time the Iron Guard joined the government of military leader Ion Antonescu and formed its Legionary State in September 1940, much anti-Semitic legislation had already been passed, and the Legionnaires were allowed to persecute Jews with impunity. This persecution intensified, becoming violent in the horrific three-day Bucharest Pogrom of January 21-23 during which the Legionnaires killed - in the most horrific manner possible - 125 Jews; women and children included. Thousands more were beaten and tortured, and two synagogues were destroyed. And worse was to come: in July 1941 as many as 13,000 Jews were killed in Iasi, in one of the worst pogroms in Jewish history. Mass killings and deportations followed, and, according to the Wiesel Commission report, released by the Romanian government in 2004, Romania in total killed 280,000 to 380,000 Jews during World War II. At the same time, 120,000 of Transylvania's 150,000 Jews died at the hands of Hungary’s fascist government (writer Elie Wiesel, the Nobel Peace Prize winner who was chairman of the Wiesel Commission, was deported with his family from Sighet to Auschwitz by the Hungarian regime). And while as many as 350,000 Romanian Jews survived the war, the Wiesel Commission states that ‘of all the allies of Nazi Germany, Romania was responsible for the deaths of more Jews than any country other than Germany itself.’

At the war’s end, mass emigration to Israel once again reduced the number of Jews in Romania. Those who remained suffered further persecution at the hands of the country’s new, Communist rulers, most notably in the early 1950s. The failure of the first Danube-Black Sea Canal project, in 1952, was blamed on Jewish engineers, who were accused of Zionism and executed. Throughout the Communist period however, Romania allowed large numbers of Jews to emigrate to Israel, in exchange for much-needed Israeli economic aid (in the 1980s Nicolae Ceausescu would pursue a similar policy with West Germany, accepting cash payment in exchange for allowing the emigration of Transylvanian Saxons). By 1987, there were just 27,000 Jews left in Romania. Further emigration since the 1989 revolution has reduced numbers even further, and in the 2011 census just 3,271 people identified themselves as Jews. Almost all of Romania’s remaining Jews live in Bucharest.

Jewish Bucharest

Almost all of Bucharest’s Jewish district - which was centred on the Choral Temple and spread from Piata Unirii east towards Dristor - was destroyed during the demolitions of the 1980s to make way for Bulevardul Unirii. The enormous Malbim Synagogue (which stood exactly where the National Library is today) was just one of hundreds of Jewish properties pulled down. Yet a handful of buildings in the area survived, and most can be visited, including the remaining synagogues (one of which hosts a Holocaust Museum), the Jewish History Museum (itself located in an old synagogue) and the Jewish Theatre, next to which is a Jewish school, Lauder-Reut.

The ‘Lost’ Synagogues

Besides the three Bucharest synagogues which still hold religious services (the Choral Temple, the Great Polish Synagogue and the Yeshoah Tova), as well as the Holy Union Temple which houses the Jewish History Museum, there are two more abandoned synagogues which can still be (just about) seen. The first, the Beit Hamidrash Synagogue, is in fact the oldest of all Bucharest’s Jewish places of worship, originally dating back to the late 18th-century. Found at the intersection of Calea Mosilor and Strada Lipscani, the synagogue is hidden behind a crumbling building and almost impossible to spot unless you know what you are looking for. The synagogue - which was badly damaged by the Legionnaires in the 1941 pogrom, has been abandoned, it would appear, for decades. A similar - although not quite so sad - fate has befallen another synagogue, built in the 1920s in the Vitan area of Bucharest. Known as the Hevrah Amuna or Temple of Faith, the synagogue is on Strada Vasile Toneanu, directly behind the Bucuresti Mall. From Calea Vitan take the first left after the Mall (Strada Vlad Judetul) and then the first left again. The Hevrah Amuna synagogue - in reasonable shape although no longer used - is on the left hand side. The synagogue’s courtyard is usually closed, although when we visited it looked as though there were people living in one of the small buildings at the rear. There were fresh flowers on the steps of the synagogue itself.

Further Reading

For a thorough account of the Holocaust in Romania, we recommend Radu Ioanid's book Holocaust in Romania: The Destruction of Jews & Gypsies by the Antonescu Regime.

For a slightly different look at life as a Jew in 1930s and 40s Romania, you can do no better than the brilliant Journal: The Fascist Years, by Mihai Sebastian.

The full Wiesel Commission Report is online at Yad Vashem.

Comments