First recorded mention of Bydgoszcz, or ‘Budegac’ as it was then known, can be traced back to 1238, though it’s thought the area was settled as early as the 11th century. Its strategic position on the Brda River made Bydgoszcz an important trading point, and by 1252 a customs house was in operation. The Teutonic Knights arrived in 1327, staking their own claim to the city. Their occupation didn’t last long, and in 1343 the town was back with the Poles as part of the Kaliski Treaty. April 19, 1346 saw the city granted its civic rights by Polish King Kazimierz the Great, meaning it could officially build schools, establish a public bath and earn revenue from the river. In layman’s terms, this marked the birth of the city. The following year saw foundations laid for the castle, and construction begin on the town’s first church.

This engraving was produced by Swedish millitary engineer Erik Dahlberg who served during this conflict. Source: Kazimierz Wielki University in Bydgoszcz.

The city continued to prosper and by the end of the 15th century it’s thought about 15% of the boats traversing the Wisła were using Bydgoszcz as their principal home. Bad times were around the corner however, as in 1655 the Swedes stormed into Poland burning and looting anything they could lay their mitts on. Bydgoszcz was not exempt from their fury, and the town took a heavy battering. The city seemed to be right out of luck, and over the following century the population was decimated by outbreaks of cholera, typhus and plague. So much so that by the time Bydgoszcz was handed to the Prussians as part of the 1772 Partition of Poland, only 1,000 people were listed as residing in the city.

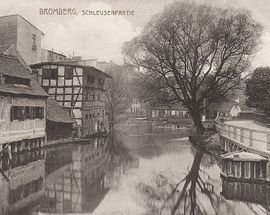

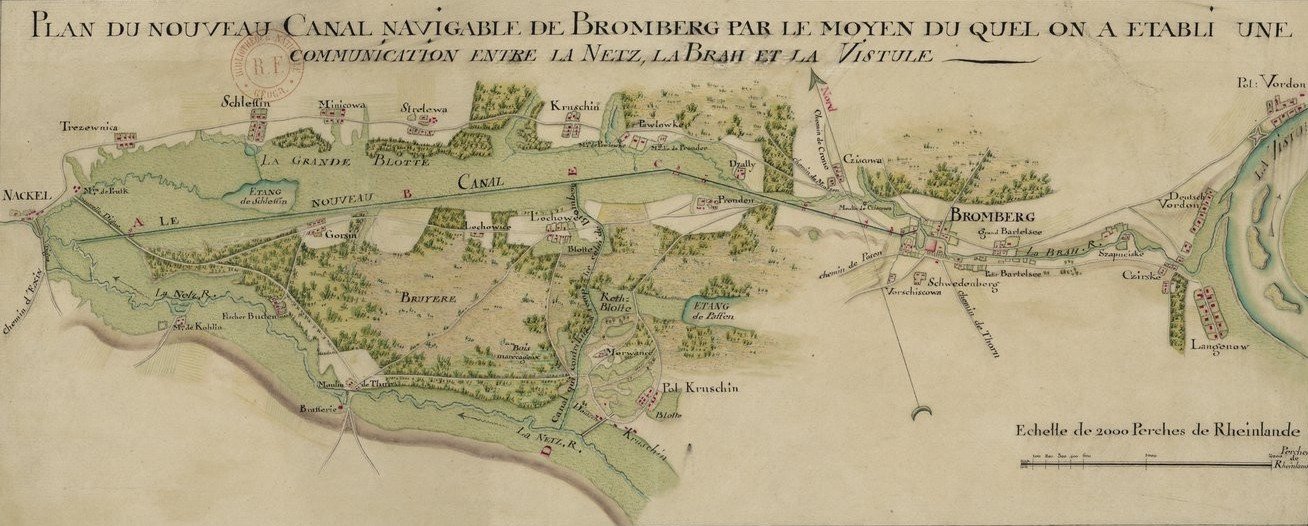

It was down to the Prussians to kick the town out of its slumber, and this they did with zeal. Craftsmen, traders and clerks flocked into the city, and within the first year of Prussian rule the decision to build the Bydgoszcz Canal was rubber stamped. Six thousand workers flooded into the city to dig the canal, and what a job they did; by 1774 the 24.7 kilometre project was complete, and at quite a cost - an estimated 2,000 labourers died in the process, most falling victim to dysentery. Although its success was far from immediate the canal was proof of Bydgoszcz’s revival. Still, ethnic tensions continued to linger and these came to a fore in 1794 when Poles rose in unison in what was to become known as the Kościuszko Uprising. For two weeks the city was under Polish control, but as with most Polish revolts it was to ultimately end in glorious failure.

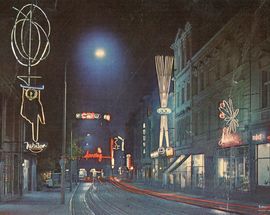

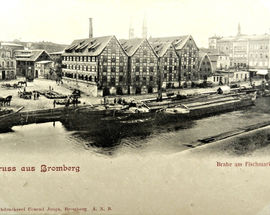

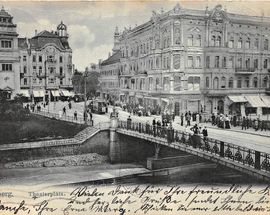

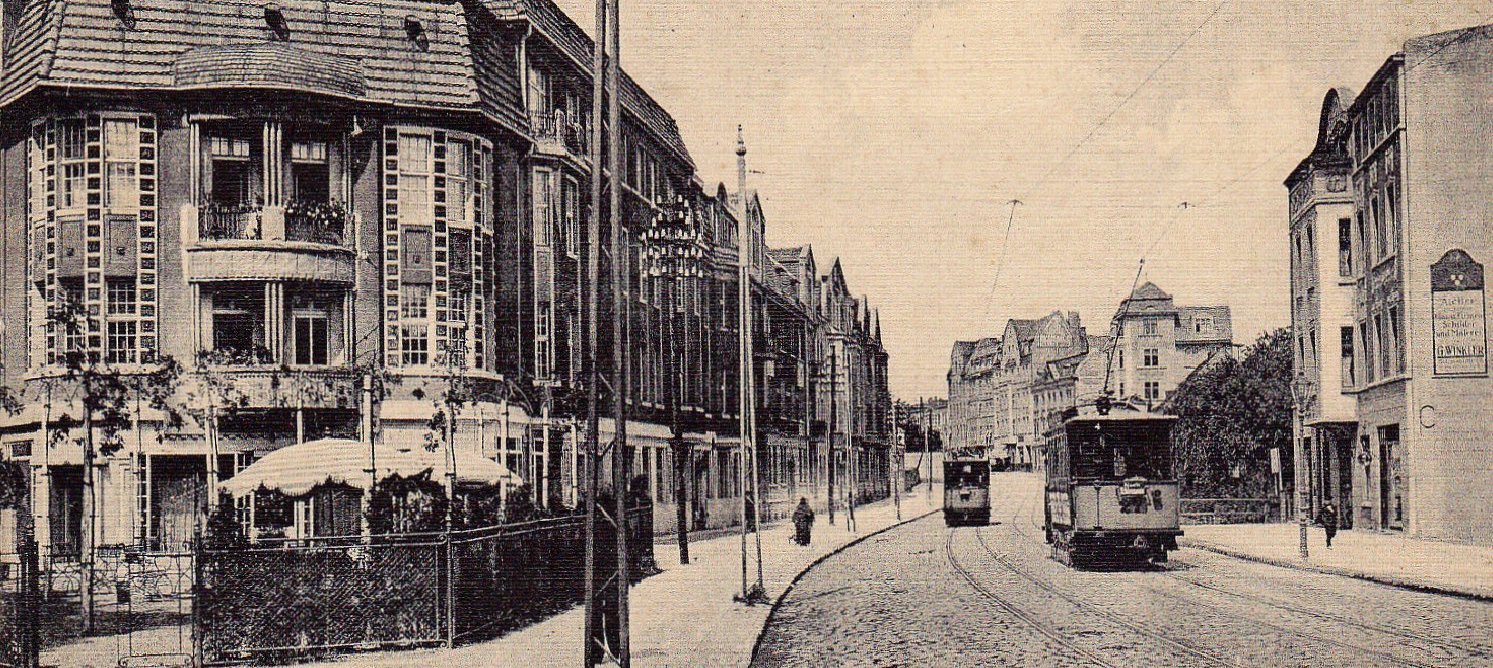

The flag on top of the Town Hall changed once more at the start of the 19th century. The year 1807 saw Napoleon marching eastwards on his way to take on the Russians, and the subsequent Franco-Prussian Treaty ensured Bydgoszcz fell under the jurisdiction of the Independent Duchy of Warsaw. But Napoleon’s failure on the plains of Russia saw the city once more returned to the Prussians and there it would remain for nearly another century. The Industrial Revolution heralded dramatic developments for both the people and city. Bydgoszcz became the HQ of the Prussian Rail system, as factories and warehouses sprang up like a rash of blackened toadstools. The city gas plant was unveiled in 1860, and by 1896 electric trams were ringing their way down the streets. By the turn of the century 50,000 people were living in Bydgoszcz, making it the fastest growing urban area in Prussia. Symbolic of this golden age is the Pod Orłem hotel on ul. Gdańska 14. Designed by Józef Święcicki, the hotel opened for business in 1896, with its elaborate neo-Baroque flourishes making it the flashiest building in town.

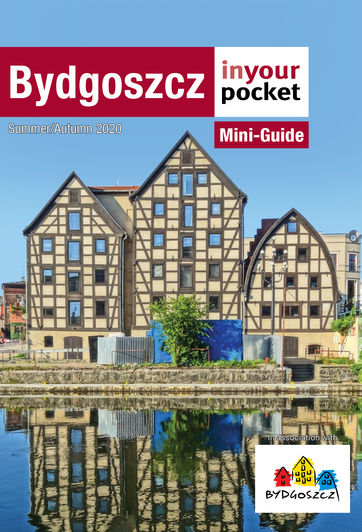

By the turn of the 20th century, Bydgoszcz was one of the fastest-developing urban centres in Poland both technologically and economically.

Source: Aukcje internetowe / fotopolska.pl

The Poles were getting restless, however, and more and more anxious to stamp their identity on the city. They finally got their chance to reclaim what they felt was rightfully theirs at the end of WWI. With the German Empire in complete disarray ethnic Poles across what is now Western Poland rose up in arms in what was to become known as the 1918-1919 Wielkopolska Uprising. The Germans fought doggedly, but were finally forced into peace talks in June of 1919. Under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles they were forced to hand Bydgoszcz over to the Poles, heralding a rapid Polonisation of the city. Bydgoszcz lost over 80% of its German population, and the natives set about reinventing the cultural and social fabric of the town.

Source: Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe (www.nac.gov.pl) / fotopolska.pl

World War Two marked the darkest chapter of the city’s history. When news of the Nazi invasion first filtered through, German civilians were massacred by the Poles, and fierce battles were fought at the Bydgoszcz Bridgehead. The superior firepower of the Nazis swamped the Polish defences and on September 5th, 1939, it was the swastika that fluttered over what the Germans knew as the city of Bromberg. Arrests and executions became standard under the new regime, and it’s estimated that 10-15,000 locals died during the war, the bloodiest of these massacres occurring on December 31, 1939 when 1,500 civilians were shot in cold blood. Six years of hell came to an end when the Red Army rolled into town on January 27, 1945, though true liberation was still a long way off.

An estimated that between 10,000 - 15,000 locals died during the war. Many were mercilessly executed.

Source: Aukcje internetowe / Fotopolska.pl

The forced adoption of communism brought with it new challenges, and while Bydgoszcz prospered as a seat of science and learning, discontent with the new system simmered. This exploded into action on November 18, 1956 when the radio station was stormed by locals. This outburst of popular opinion – and many like it across Poland – was brutally suppressed, and the continual decline in living standards sparked a fresh wave of protests in 1981. Inspired by Lech Wałęsa’s Solidarity movement workers across the country put down their tools and went on strike. The declaration of Martial Law bought the nation to heel and the government set about stamping out instances of subversion. Dissenters and sympathisers were arrested and imprisoned, while Jerzy Popiełuszko - a Solidarity-supporting priest - was murdered by security services in 1984 having just conducted a fiery sermon in Bydgoszcz. His funeral in Warsaw was attended by 250,000 people, and the spirit of protest continued to linger.