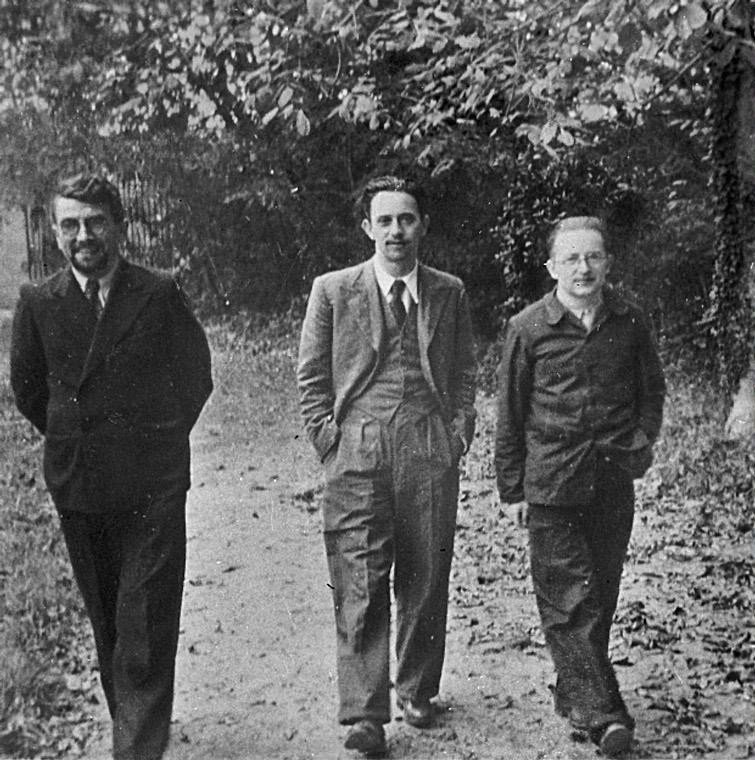

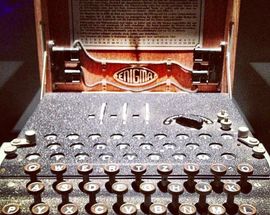

It all began in Poznań, namely in the mathematics class of the university. Ace students Jerzy Różycki, Marian Rejewski and Henryk Zygalski came to the attention of Polish intelligence services on account of their excellent German skills and sharp mathematical minds. Recruited to attend cryptology courses in Warsaw alongside 17 other Poznań University alumni, the three were set to work in 1932 on cracking German ciphers. It was in the city's Saxon Palace, which served as the seat of the Polish General Staff, they made the first vital Enigma breakthrough using a mathematical theorem since described as ‘the theorem that won WWII.’

On the day before the Nazi invasion of Poland the three fled to Romania where they immediately sought contact with the Allies. Originally they turned up at the British Embassy in Bucharest, but having been told to ‘come back in a few days’ decided to try their luck with the French instead. This proved more successful and from there they found themselves in France, working in Cadix, a secret intelligence cell operating in the unoccupied south. With the risk of discovery by the Germans growing greater the team were forced to flee. Różycki drowned at sea in 1942 after the boat that carried him sank under suspicious circumstances; Zygalski and Rejewski however made it to Spain, in spite of being robbed by the man guiding them over the Pyrenees.

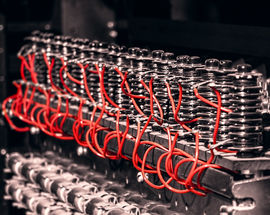

More calamity followed: the remaining pair were arrested by Spanish police and imprisoned, but freed the following year after intervention by the Red Cross. Seeking sanctuary in England they were employed in Boxmoor cracking simple SS codes. In spite of having done the groundwork that broke the original Enigma code their knowledge was not called on by the American and British codebreakers who were cracking new and improved Enigma codes at Bletchely Park, hence the vital Polish contribution has been allowed to fade in the memory.

After the war Rejewski returned to Poland where he spent the rest of his days under scrutiny from internal security services, and working in a succession of menial jobs. When he published his life story in 1973 he became an unwitting superstar, and his work was finally recognised with a series of honours. He died in 1980, buried in Warsaw’s Powązki Cemetery. Zygalski chose to remain in England and spent the post-war years working as a math teacher. He died in 1978 and is buried in London. Although the trio have since received numerous posthumous awards, their role in winning the war remains a little-known fact in the West, a cause not helped by silver screen rubbish like the 2001 movie Enigma.

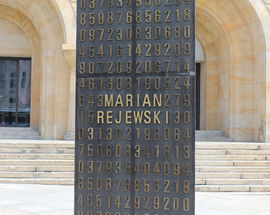

In recent years, recognition for the Polish codebreakers has come, even if sometimes it's only a passing remark such as Alan Turing's about an 'old Polish code' in The Imitation Game (2014). Since 1983 a memorial tablet at Poznań University’s Collegium Maius has been in place honouring the three, and in 2006 an obelisk bearing their names was unveiled on ul. Św. Marcin in what was formerly the Maths Department of the uni.

The BBC's Gordon Corera has written a good article about the 'overlooked Enigma codebreakers' on the BBC website.

Comments