History produces few men like Tadeusz Kościuszko (1746-1817). Men who by the depth of their skills, the purity of their beliefs, the compassion in their hearts and their uncompromising commitment to a cause are able to inspire not only individuals, but entire nations.

Kościuszko's highest ideal was freedom, and he used his own to try and secure it for all those less fortunate. In one country - Poland - he failed and is remembered as the greatest hero who ever walked the land. In another country - America - he succeeded, and yet has been almost completely forgotten.

To learn about his amazing life and accomplishments and why we firmly believe he is the greatest Pole of all time (GPOAT), please stop your life and read this long-form. It will inspire you.

Say My Name

Though commonly anglicised as ‘Thaddeus Kosciusko,’ and despite adorning dozens of streets, bridges, parks, monuments and other world landmarks - including an island in Alaska and Australia’s highest mountain - the name ‘Kościuszko’ has ultimately proven too unpronounceable to those outside of Poland to secure this great man his rightful place in history. No one remembers a name they can’t pronounce, after all. That’s why we want you to get hooked on phonics and say it with us now:

Koash-choosh-ko.

Koash-choosh-ko.

Koś-ciusz-ko.

Kościuszko.

The Early Years: Education & Heartbreak

Born to parents of noble lineage but modest means in a small, now non-existent village within the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in modern day Belarus, young Kościuszko received a well-rounded ‘gentleman’s’ education before shipping off to Warsaw in 1765 to enrol in the Cadet Academy. Rather patriotically trained as a military engineer, Kościuszko achieved the rank of Captain and was granted one of only four royal scholarships to continue his education in Paris. Devoting himself to military study for the next five years, Kościuszko basked in his exposure to the ideals and philosophy of Enlightenment-era Paris, however he was beset by financial problems and could only watch from afar as his country was carved like a Thanksgiving turkey by its land-grabbing neighbours Russia, Prussia and Austria during what became known as the 'First Partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth' (1772).

would someday end up on the 500zł banknote!

Finding his country enslaved and pandering to outside powers, Kościuszko retired to the Polish countryside where a job was arranged for him teaching the children of one of the richest men in Poland, Lord Sosnowski, a friend of his father’s. The penniless Kościuszko soon fell in love with one of his pupils, Ludwika Sosnowska, whose petite hand had already been promised in marriage to Prince Lubomirski. With the Prince onboard, Ludwika's father condemned her relationship with the pauper Kościuszko and accounts vary as to whether Tadeusz and Ludwika attempted to elope, Tadeusz kidnapped her, or they were separated before he had the opportunity to liberate her from the marital arrangement made on her behalf. Having lost the woman that was to be the only love of his life, however, Kościuszko was either forced or felt compelled to flee the country.

Eventually Kościuszko returned to Paris where all the buzz of the day was about the American fight for independence. The French, who went about aggravating the British and undermining their interests abroad with special zeal, openly supported the outbreak of the American Revolution, romanticising its ideals to the impressionable Kościuszko. Seeing an opportunity to apply his credentials to a cause complicit with his own beliefs, Kościuszko emigrated to America and joined the struggle.

Koścziuszko: 'Real American Hero'

Arriving at the age of 30 in Philadelphia, the cradle of the Revolution, Kościuszko was quickly put to work fortifying the crucial city’s defences along the Delaware River. These defences, which were never tested by the British, remain to this day and earned the Pole the confidence of the American command and the rank of Colonel in the engineering core. Sent to the Northern Army under the command of General Horatio Gates, who took an instant liking to his engineer, Kościuszko was asked to report on the defences of the Hudson River which were underway at Ticonderoga.

Appalled by the poor strategy in place and frustrated over his suggestions being superseded by flawed wisdom, the Pole remarked, “I would choose rather to leave all, return home and plant cabbages.”

Supervising the strengthening of Fort Ticonderoga, Kościuszko’s ignored assertion that cannons be mounted on nearby Sugar Loaf Hill came back to bite the Americans as the British instead took the position and forced them to abandon the fort with hardly a shot fired. Kościuszko would soon get his vindication however, gaining all credit from the American command for his choice of Bemis Heights as the place to engage the enemy when the American side scored victory in what would become the decisive turning point of the war – the Battle of Saratoga in October 1777. The victory at Saratoga not only won the northern campaign, but also earned the American colonies the alliance of the French as Louis XVI officially recognised America as an independent country.

Private cabbage planting comments aside, Kościuszko won favour in America not only for his intelligence and expertise, but also for his treatment of the troops, humility and general agreeability – the latter of which was an occasional point of contention between the American command and Kościuszko’s Polish compatriot Kazimierz Pułaski. It also sealed his appointment over the French engineer Radiere as the man in charge of fortifying the critical position known as the ‘American Gibraltar’ - West Point, New York. With a workforce of 2,500 under him, Kościuszko spent the next two years building the impenetrable fortress that would later become America’s premier military academy, as suggested by Kościuszko to General George Washington when they met there in the first of several encounters.

Kościuszko left before West Point was finished however, wishing to join his friend Gates in the southern campaign. In a less than trivial side note to a well-known story of the American Revolution, it was Kościuszko’s plans for West Point that the traitor Benedict Arnold attempted to sell to the British after he took over command of Kościuszko’s abandoned post.

Upon his arrival to Philadelphia at the outset of the war, Kościuszko had wasted no time in reading The Declaration of Independence and found himself so moved by its language, inspired and in concert with its ideology that he determined to meet the man who wrote it, Thomas Jefferson. En route to joining the southern campaign he stopped in Virginia to meet with Jefferson and the two men began a lifelong friendship which became so binding that Kościuszko later made Jefferson the executor of his will (having never married or had children). In describing Kościuszko to Gates, Jefferson called him “the purest son of liberty among you all that I have ever known, and of that liberty which is to go to all, not to the few or the rich alone.” It was in Virginia and his time in the South that Kościuszko was also made acutely aware of the inhumanity of the slave trade and the troubling plight of Africans indentured throughout the South, which he later attempted to use his moderate means to alleviate as much as he could.

When Kościuszko reported to the Southern Army, Gates had been deposed following a disastrous defeat at the Battle of Camden and Kościuszko served the rest of the war under his successor General Nathaniel Greene, who held the Pole in the highest esteem. Together they orchestrated the re-conquest of the Carolinas and Georgia, in which Kościuszko’s expertise as a scout, engineer, soldier and commander proved indispensable. During the campaign, which involved guerilla-like warfare across inhospitable terrain, Kościuszko saw extensive action as a soldier and was very nearly killed on several occasions, sustaining a bayonet wound to the posterior in one engagement. He finished the war in Charleston, South Carolina, finally applying his engineering prowess to a spectacular fireworks display upon news of the signing of the Treaty of Paris in April of 1783.

Having distinguished himself in his valorous service to the American cause, upon the war’s conclusion Kościuszko was promoted by Congress to the rank of Brigadier General, given American citizenship and granted a huge parcel of land near present day Columbus, Ohio. However Kościuszko wanted nothing more than to return to his native Poland, whose sovereignty was increasingly threatened by its aggressive neighbours.

Kościuszko on the Rise

When Kościuszko returned to his boyhood home in 1784, there were many peasants under his authority whose labour he immediately reduced, freeing the women from serfdom and cutting the obligations of the men to two days a week. As a result he lived in poverty tending his own farm and gardens, the stipend he was supposed to receive from America suspiciously failing to ever reach him and not being of his particular concern. Having arrived in his struggling nation with an enhanced adherence to the democratic ideas which had attracted him since his earliest days, and with the first-hand experience of how a largely untrained and unpaid volunteer army could defeat a much greater opponent through the sheer strength of their belief in the cause and their passion for freedom, it should come as little surprise that Tadeusz Kościuszko’s retirement was quite short-lived.

photo by Viktar Palstsiuk CC BY-SA 4.0

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth at this time was making a belated effort to strengthen itself against the surrounding powers through controversial reform, and when The Great Sejm of 1788-92 initiated the creation of a large army to defend its borders Kościuszko found himself being drawn back into the military sphere. On May 3, 1791 the Commonwealth created the first constitution in modern Europe (second in the world after America), enacting widespread reforms and unwittingly provoking the surrounding powers, who felt their influence over the politics of the Commonwealth were threatened. Four days after the passing of the constitution, the Russian army (wouldn’t you know it) crossed the border headed for Warsaw, triggering the Polish-Russian War of 1792.

Kościuszko had already applied himself to the country’s new army under commander-in-chief Prince Józef Poniatowski. Betrayed by their supposed Prussian allies who did not oppose the advancing Russians, Poniatowski and Kościuszko defeated a much larger army at Zieleńce, and Kościuszko was among the first recipients of the newly minted Virtuti Militari medal which remains PL’s highest military decoration to this day. Earning the reputation of Poland’s most brilliant military commander at ensuing battles, King Stanisław Poniatowski promoted Kościuszko to Lieutenant General, however the cause was immediately lost when the King suddenly surrendered to the Russians before word of the worthless promotion had even reached Kościuszko’s camp. The 'Second Partition of Poland' (January 21, 1793) was set in motion, Polish independence was restricted and its population shrank to one third of the size it had been before 1772. Outraged by the King’s capitulation, Kościuszko – who hadn’t lost a single battle of the short-lived campaign – and the other notable commanders and politicians still faithful to the cause emigrated to Leipzig to plot an uprising against Russian rule in Poland.

The 'Kościuszko Uprising'

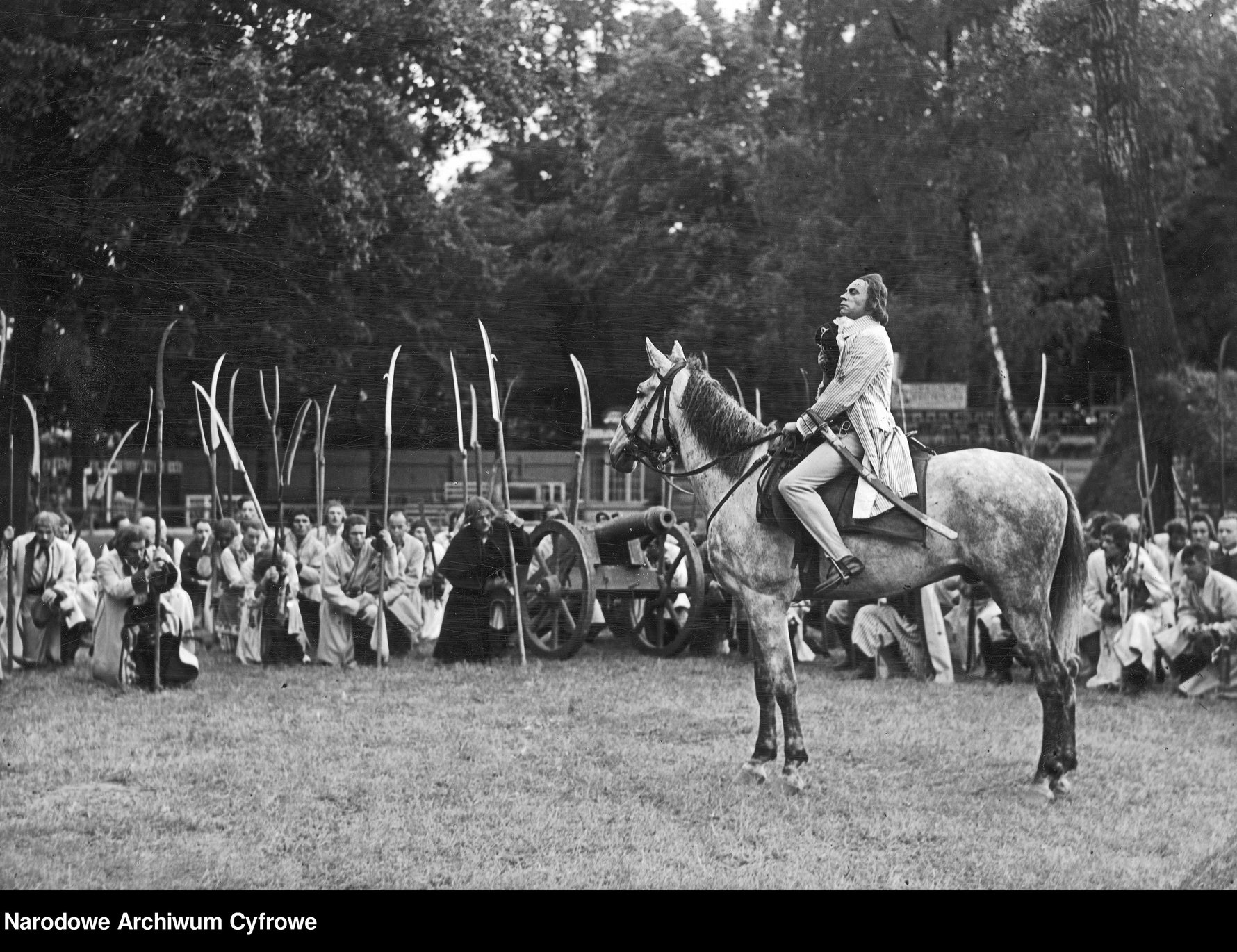

In the aftermath of the Second Partition of Poland, those constituencies of the population which had opposed the reforms of the May Constitution had lost all credibility and Kościuszko saw the prospect of orchestrating a successful national uprising as less than impossible and more than necessary. Organisation was extremely difficult, however; preparations were slow and unrest was breaking out as the Russian and Prussian governments dissolved the Polish Army and arrested supporters of independence. With the outlook increasingly desperate, Kościuszko was forced to execute his plan before he wanted and announced the Uprising on Kraków’s market square on March 24th, 1794. Assuming the powers of commander-in-chief of all Polish forces, he issued an act of mobilisation requiring at least one able-bodied male from every five houses in Małopolska to join his army equipping themselves with an axe, pike or carbine. Arming the troops proved to be a problem and Kościuszko was forced to form large units armed only with scythes, a new homemade variation of which he is credited with designing during the Uprising.

Seeing that Kościuszko lacked a professional army, the Russian Tsarina Catherine the Great quickly ordered an attack on Kraków hoping to quash the Uprising in one blow. On April 4th the two sides collided near the village of Racławice, with Kościuszko’s forces actually having the man advantage if you include all the peasants with sharp sticks. After a bloody battle they won the day, but were too weak to pursue the Russian troops, who remained in the area. Though of no lasting strategic significance, news of the Polish victory spread quickly, rousing great support for Kościuszko’s Uprising. Today the battle is still a source of national pride and also considered to be the beginning of the Polish peasantry’s ascension from second-class serfs to equally entitled citizens.

This amazing immersive painting can be viewed in Wrocław today.

Inspired by Kościuszko’s victory, insurrections broke out across Poland, particularly in Vilnius and in Warsaw, where a 6,000 strong Russian garrison was forced to evacuate the city. On May 7th, 1794 Kościuszko issued the ‘Proclamation of Połaniec’ – a less snappy-sounding fore-bearer of Lincoln’s 'Emancipation Proclamation' in which he partially abolished serfdom in Poland and granted civil liberties to the peasantry. Though the law never fully came to fruition and was rejected by much of the nobility, it was a landmark announcement and did much to draw peasants into the conflict. Kościuszko’s ideals had mass appeal to all the oppressed; in what has become a historical footnote, Józef Berkelicz called Kościuszko a ‘messenger of God’ and founded a Jewish cavalry unit to fight at his side – the first all-Jewish military unit since biblical times.

Despite the steady and swift recruitment of forces, the Polish defeats began to accumulate once Prussia entered the war in an alliance with Russia. Kościuszko was defeated in the Battle of Szczekonicy and Kraków was captured uncontested soon afterwards. Though an uprising in Wielkopolska was enjoying some success, a newly equipped Russian corps was advancing on Warsaw in an effort to join the existing Russian force. To prevent their coalition, Kościuszko boldly, fatalistically provoked the Battle of Maciejowice on October 10th, making a misjudgement and bearing the brunt of both armies which engaged him simultaneously. His army outmanned by more than four to one, Kościuszko was wounded and captured in the crushing defeat. Things only got worse for new revolutionary commander Tomasz Wawrzecki as a vicious Russian assault on the Warsaw suburb of Praga destroyed the district and claimed the lives of 20,000 inhabitants. On November 5th, Warsaw was captured and less than two weeks later Wawrzecki was forced to surrender. The flames of revolution had been extinguished across Poland and a year later the 'Third Partition of Poland' (October 24th, 1795) divided its lands between Austria, Prussia and Russia, officially erasing it from the jigsaw of Europe for what would transpire as the next 123 years.

The Later Years: Exile

In a state close to death, Kościuszko was taken to Saint Petersburg and imprisoned with his closest surviving comrades and advisors within Prince Orlov’s Marble Palace where they remained for two years. Here he was generally well-treated, however his wounds had been poorly tended and he would be crippled for the rest of his life. Upon the death of Catherine II in November 1796, amongst the first acts of the new Tsar Paul I – a man with profound sympathy and respect for Kościuszko’s dedication to his country – was to pardon and release him, along with 12,000 Polish prisoners from the Uprising, under the condition Kościuszko swear an oath of allegiance to the Tsar. After a morally excruciating deliberation, Kościuszko resigned to the oath and left Russia to make the long journey to what he considered his second home, America.

where Kościuszko lived upon his return to the US.

Today a museum operated by the National Parks Service.

Kościuszko received a hero’s welcome upon arrival in Philadelphia on August 18, 1797. Here he lived for a year entertaining old friends, principally soon-to-be US president Thomas Jefferson, who quickly arranged his secret passage to Europe, obtaining him false documents and the means of the journey, when Kościuszko felt he could do service to his country once again by negotiating with Napoleon.

Before he left America, Kościuszko entrusted Jefferson with his last will and testament, which stated that the money from the substantial estate he had been granted (and never visited) be used to free and educate Jefferson’s own, and as many additional, black slaves as possible. Jefferson, betraying his friend, later failed to execute the will and none of the designated money was used for the betterment of blacks, though the first school for coloured people in America was named for Kościuszko, opening in Newark in 1826.

Further Reading

By Alex Storozynski; published by Thomas Dunne Books

If you think we’ve exaggerated the extent to which Kościuszko has been forgotten or underappreciated by western historians, you could kindly explain how a scholarly account of his life and accomplishments went unwritten in English until 2009. Fortunately Pulitzer-winning author Alex Storozynski rectified that, writing a well-researched, comprehensive and colourfully told biography that paints a complex and humanitarian portrait of its subject which should do much to retrieve Kościuszko from obscurity and return him to his proper place in history. Available in hardback, paperback, and kindle editions, The Peasant Prince is highly readable and highly recommended.

Comments