World War II was the most globally-extensive, most deadly, and most deadly conflict in human history. And it began right here in Danzig/Gdańsk...

is generally considered to be the first shots ever fired in World War Two.

Unbeknownst to a European continent still healing its wounds in the two short decades since World War I, the unavoidable and terrifyingly quick successor to what had been idealistically referred to as the 'War to End All Wars' would prove to be even more devastating and destructive; and a more lasting tragedy.

Prelude to war

Endlessly caught in a tug-of-war between Germany and Poland, the end of World War I saw the League of Nations come up with a hare-brained solution to the ceaseless bickering – it matched the city to neither suitor, instead assigning it the title of The Free City of Danzig. Despite the large German-speaking population, Germany was in no condition to look after Danzig's citizens, while giving it to the newly-reformed Polish state was a gamble; would the Poles side with their Slavic brothers to the east and turn red? Anything was possible in this volatile post-war Europe, and the thought of Danzig/Gdańsk – then a hugely important international trading route – falling into the hands of the communists was too much to bear. And so it was that Danzig/Gdańsk became a semi-independent state, a result which pleased neither Germans nor Poles. Part of the newly-reformed Polish state also included a thin strip of land of forfeited German land to the north-west, west and south-west of Danzig, the Polish Corridor, designed to give Poles access to the Baltic.

Although still a 'Free State', German censorship was already in effect by this time.

Outbreak

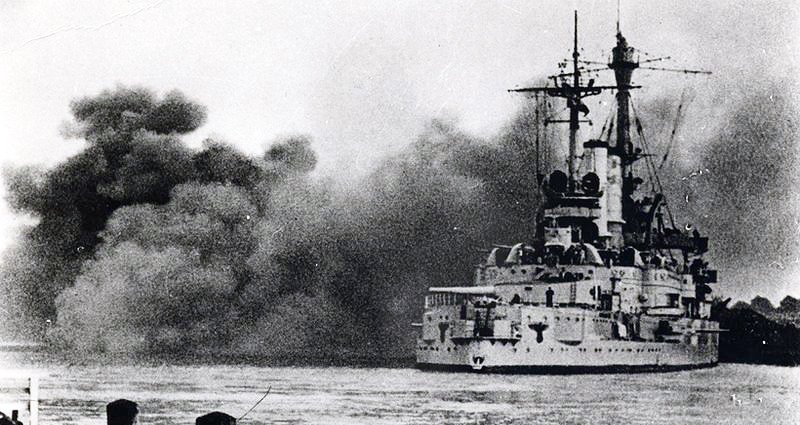

On August 31, 1939, Nazi units dressed in Polish uniform infamously staged a mock attack on a radio tower in the German border town of Gleiwitz (now Gliwice). Photos of the charade were flashed across the world, with Hitler claiming a provocative attack by the Polish army. The following dawn, Germany launched a strike on Westerplatte - the attack that would ultimately kick off World War II.Popular theory asserts that the first shots were fired from the German warship the SMS Schleswig Holstein, supposedly visiting Gdańsk on a goodwill mission. Wrong. Logbooks recovered by the Nowy Port Lighthouse prove beyond doubt that the German battleship was pre-empted by a matter of three minutes by a Nazi machine gun emplacement nestled halfway up the lighthouse. The Poles, taken aback, missed this target entirely; their second attempt scored a direct hit, credited to Eugeniusz Grabowski, thereby in all likelihood making the German lighthouse gunners the first casualties in a war that would go on to claim 55 million lives.

The forest that previously existed here was completely destroyed during the invasion.

Nazi siege of Danzig

Yet while the post office capitulated, the garrison at Westerplatte – numbering around 220 men – held on. The plan was simple: in the event of an attack in Gdańsk, the Polish navy, stationed in nearby Gdynia (Poland), would sail in to help, aircraft from Puck would be scrambled, and the bridge in Tczew would be blown to stop a German advance into what was the de-militarized zone of the Free State. As it transpired nearly everything that could go wrong for the Poles, did. The navy was caught out in the Bay of Gdańsk, while the air force was destroyed while still on the ground. Polish customs officers did succeed in blowing the bridge at Tczew, crucially slowing the German advance whose armour was gathered over in Szymankowo. They paid for their bravery with their lives, and all were later shot by their German opposites, themselves also armed and primed for war. Today, the Stutthof museum has a post-execution picture of a grinning Nazi shooting party taken outside the Pullman wagons in which the Polish officers had lived.

Danzig under the Reich

Hitler had always made much of incorporating Danzig into the Reich, yet somewhat surprisingly he only made two visits to the city – a deep held suspicion of Danzigers, and a fear of assassination explaining such apathy. The second of these visits came on September 18, 1939, with an exultant Fuhrer arriving to Sopot on board his armoured train, the Amerika. It was there he checked into the Kasino Hotel (today the Sofitel Grand), booking into rooms 251-253. His stay lasted a week, during which time he received a delegation from Japan, visited the Schleswig-Holstein, Westerplatte and inspected a parade outside Dwor Artus on Gdańsk’s Dlugi Targ.By this time fervent Nazis were already clamouring to rid the region of all traces of Polonization. The Intelligentsia and other political targets were arrested and incarcerated in numerous camps and prisons, including the Victoriaschule, which was used as a interview and processing centre, the city jail (now replaced by a newer model) and Stutthof – later to morph into a notorious concentration camp. Flags, signs and anything else remotely Polish was destroyed, and even today visitors can view a Polish eagle in the Free City Museum, its form clearly scarred from the rocks thrown at it.

Governor and Gauleiter of the region was Albert Forster, and his reign still arouses controversy and debate among both scholars and survivors. Unlike other Gauleiters in annexed and occupied territories, Forster followed a program of assimilation, granting thousands of locals German citizenship if they swore German heritage. Even more remarkably, those Poles rounded up and persecuted in the first wave of arrests could seek German citizenship, and even pursue compensation and restitution for any property originally seized. Benign by some benchmarks, Forster was a model Nazi on others. Jews faced merciless persecution, Stutthof emerged as a true place of terror and he is personally thought to have given the order for the murder of over 2,000 Poles executed between 1939 and 1940.

The estimated number of inmates killed is between 63,000 - 65,000, which includes 28,000 Jews.

Today traces of Forster’s Danzig are scant – his country retreat on Wyspa Sobieszewksa, where he hunted and lived in extravagant style, is today fenced from prying eyes. His Danzig home in Oliwa has been pulled down, and the secret escape tunnel running from Party HQ in Wrzeszcz to the foot of a hill in the Siedlice district (ul. Kartuska 135L) has long been bricked up. Eventually caught on the Hel Peninsula while trying to flee westwards, even his death remains a mystery – some claim he was hung in Biskupia Gora after the war, while others insist it was his body double who faced the hangman. Yet more sources claim he was taken to Warsaw’s Mokotów Prison and beaten to death. The truth, it appears, will never be known.

Soviet siege of Danzig & Finale

For ordinary Danzigers the quality of life remained relatively good for much of the war. Zoppot/Sopot, especially, became a favourite stamping ground for soldiers on R&R, and in spite of rationing and occasional shortages life didn’t get worse until the closing stages. The first warning signs that all was not well came with the first air raids, yet even so Allied bombers targeted the shipyards – home to munitions factories producing U-Boats and V1 and V2 rockets – and the Zaspa airfield. The war still seemed far off, even in 1943 when work commenced on whisking cultural treasures to locations westwards.

By 1944 a different picture had emerged; Danzig had become a major transit point, not least with swarms of refugees fleeing from the east, as well as a regular target for bombing raids. By March, 1945, with the Red Army fast approaching, the population had reached 1.5 million and the city stood on the precipice of chaos. Suspected deserters were strung up from the lampposts and trees of al. Zwyciestwa (or Hindenburg Allee as it was then known), and the city descended into a Dantean vision. Historian Antony Beevor writes of the ensuing siege: ‘Fighter bombers strafed the towns and port areas. Soviet Shturmoviks treated civilian and military targets alike. A church was as good as a bunker, especially when it seemed as if the objective was to flatten every building which still protruded conspicuously above the ground... Tens of thousands of women and children, terrified of losing their places in the queues to escape, provided unmissable targets.’

WWII Sightseeing in Gdańsk

Any visit to Gdańsk would not be complete without a thorough visit to the Museum of the Second World War, 15 mins walk north of Gdańsk Old Town, which has a fantastic and very extensive permanent exhibition to experience. Nearby is the former Danzig post office building, which still bears the scars of the 1939 siege and is now both a museum and a Polish post office. The Westerplatte peninsula is now a historical park and memorial site, featuring a scattering of shelled bunkers, burnt-out ruins, and a small seasonal museum in the pivotal Guardhouse Number 1. Across the way is the Nowy Port lighthouse in the district of the same name. Both areas are located 30 mins by bus from Gdańsk Old Town, in addition to a ferry operating along the Martwa Wisła in summer. Numerous German bunkers can be seen in the coastal forest areas between Sopot and Gdynia, most notably in Kępa Redłowska, and also at the tip of the Hel Peninsula. The remnants of Torpedownia, a short-lived German torpedo-testing facility, can be viewn from the coast in Northern Gdynia. The open-air museum of the Stutthof Death Camp is an 80-minute bus ride from Gdańsk Główny Bus Station.

Comments