We attended the announcement at Keyes Art Mile March in Rosebank and were struck by his focus on indigenous knowledge systems and his interest in foregrounding this at the world's most prestigious architecture exhibition.

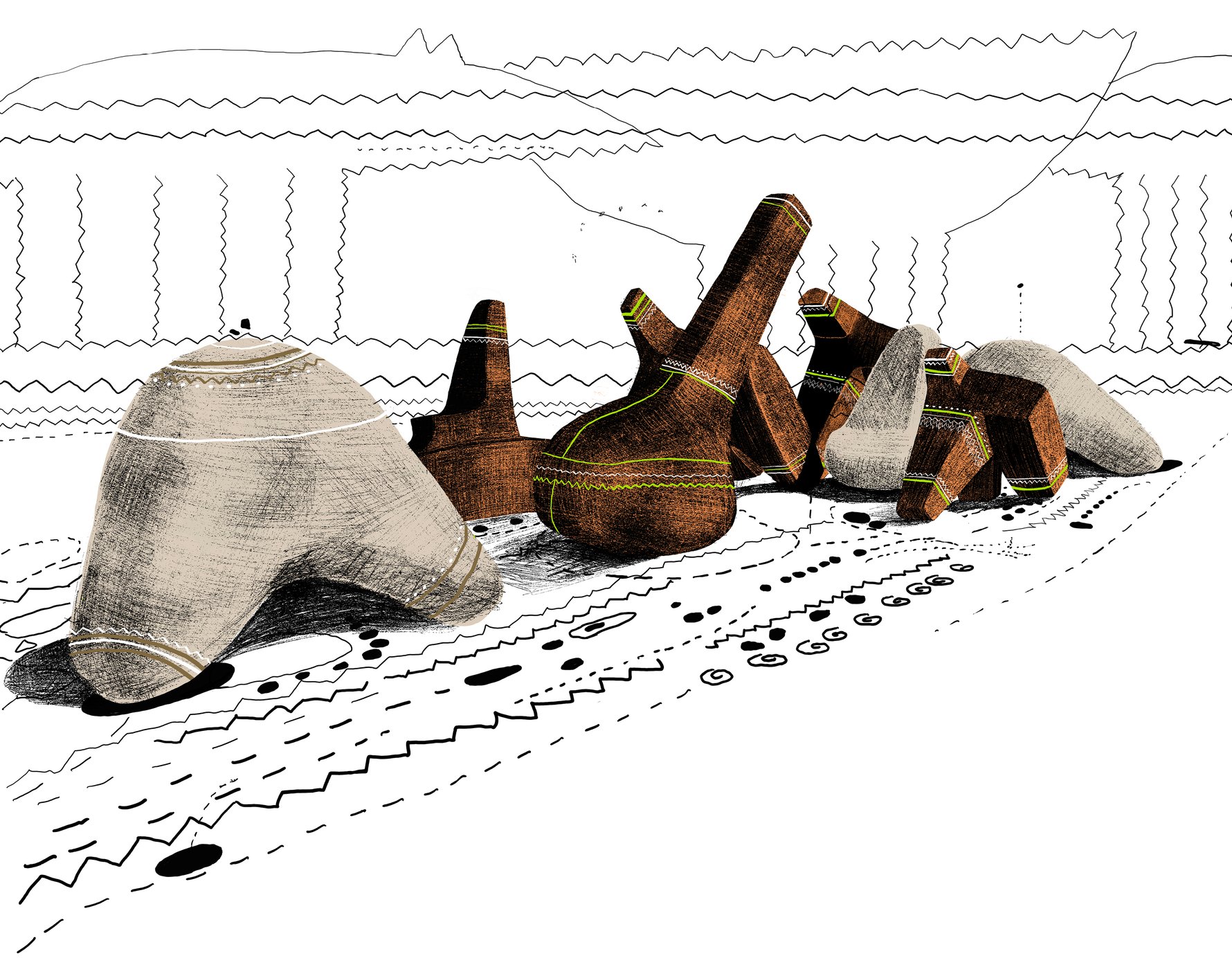

The theme chosen for the Biennale Architettura 2023, is The Laboratory of the Future, and with this in mind Maape delved into the past to bring together his exhibition for The Council of Beings. It will feature his research-practice drawings that point to a future in which non-western, and Pan-African traditions of thought are introduced to the epistemological realm of architecture.

"I believe that is because the logic of architecture is still predominantly Western, and for example in Western architecture one would ordinarily not think of the landscape as being alive. So indigenous knowledge has a place by generating other ways of seeing the world."

'Scattered over 10000 square kilometres of grassland in Mpumalanga, about 200km two hundred east of Johannesburg, lie the ruins of a vast pre-colonial civilisation known as the Bokoni. Of particular architectural interest at this site is a large number of low-relief rock carvings that depict building plans. It is widely agreed that the plans were not intended for construction, but constitute a theoretical architectural representation, demonstrating that Bokoni herdsmen made drawings of social structures as they are represented by architectural plans.'

Maape's exhibition, titled The Structure of a People draws on formerly peripheral value systems that rely heavily on the appreciation of pre-colonial values to engage contemporary conditions such as ecological change and inequality. He has studied indigenous knowledge systems to reimagine contemporary human settlements, institutions, and communities into the future. We find this approach fascinating as a basis for architectural thinking and design, and wanted to delve further so we had to ask Dr Maape some questions.

What defines your practice?

My practice is defined by the 10 years of field work research in which I have been studying indigenous knowledge systems and spaces in my hometown of Kuruman. The research found that some people in Kuruman see the landscape as a living being, mostly represented in this way through narratives in the area. One such story is that of the water snake, an entity that is evoked when people encounter various natural phenomena. This has developed a philosophy in my practice which aims to design equally alive architecture in response to a living landscape. It ultimately questions how we see context, and how this influences our architectural response.

You mentioned you grew up in a “matchbox house” near Kuruman in the Northern Cape. Today you are a lecturer at the Wits School of Architecture and Planning. Tell us about that journey.

My childhood was in Kuruman in a small township called Mothibistad, however in the early 80’s my family moved to Cape Town because my father was a political prisoner in Robben Island. When he was released in 1990, we stayed in CT and later moved to JHB, and eventually to Mahikeng where I did my high school. After high school I applied to study architecture at Wits, where I did my undergrad, my postgrad and my PhD. Eventually I was appointed as a staff member and have been there since. I continue to visit Kuruman, my family still live there and we still own our matchbox house.

"When we design, we have to think of new ways of approaching the landscape, with respect and reverence, and also recognising that our actions will have implications. I believe the reason we have climate change today is that our way of seeing nature as an object restricted us from seeing the consequences of our actions, and so for me having empathy for the landscape is the beginning of changing our practices."

Your submission for the South African Pavilion at the 18th International Architecture Exhibition in Venice foregrounds indigenous knowledge. What place does this have in thinking about architecture?

In my own research this has been linked to seeing the land we build on in a different way, resulting in new questions for architecture. For my Masters thesis, I chose to explore indigenous knowledge systems, however, no one could really guide me as a supervisor because the kind of knowledge I later uncovered through my PhD was not existing in the academy. I believe that is because the logic of architecture is still predominantly Western, and for example, in Western architecture, one would ordinarily not think of the landscape as being alive. So indigenous knowledge has a place by generating other ways of seeing the world, which may represent the world views of previously marginalised people, and therefore producing spaces that respond more appropriately to people's needs.

What was your earliest memory of coming into contact with indigenous knowledge systems, and how did this shape your career?

It is probably as early as my earliest memories, maybe three or four years old. When growing up, people would tell me that the water snake is going to take me because my eyebrows are connected. Later I realised that this is a part of Khoe Khoe culture. Girls going for initiation who have connected eyebrows were considered beautiful, and the snake was attracted to them.

You speak about landscape as a living thing, and that implies that building on land is a confrontation of sorts. Tell us more about this.

When we design, we have to think of new ways of approaching the landscape, with respect and reverence and also recognise that our actions will have implications. I believe the reason we have climate change today is that our way of seeing nature as an object restricted us from seeing the consequences of our actions, and so for me having empathy for the landscape is the beginning of changing our practices. This is not new in Africa, like how people recognise that the landscape needs to replenish itself, and move grazing animals periodically for example. This is understanding that the land is a living being.

You said you are tired of white and grey buildings. Why?

I think all cultures and people should express what they think is beautiful. That could be anything, including white and grey, I just don’t agree with a dominant aesthetic. Furthermore, Africa is known for being a colourful place, and South Africa is so diverse. Why should we not have equally colourful buildings?

What defines Joburg’s architecture now, and what would you like to define it a century from now?

I think it is capitalism, and what developers think needs to be built. I think we need creative and daring developers who recognise the potential of introducing diversity. I think in a century [from now] we should be a city that represents diversity and cosmopolitan vibrancy

Why do we still have matchbox houses?

I think poverty, and several complex socio-political situations.

You mentioned that for the Biennale, the installation has dealt with blackness in a radical way. What can an audience expect to see?

White has a history, black also has a history: black magic, the dark continent, etc. We want to reclaim and reframe black as a colour. I can’t say much here but know that black is a main thematic colour.

How has rock art influenced your thinking?

Rock art from South Africa is where I first saw people doing drawings that represent the landscape as being alive, hence I have adopted similar principles, but applying them in contemporary times. Sometimes the landscape is depicted as a snake, sometimes rain clouds as a hippo and so on. The point is that these entities were understood as alive in some way, not necessarily literally. Khoe and San people would not think that a cloud is a hippo, but understood that at some deeper level, it has its own life.

If you wanted to show someone rock art in Joburg, where would you take them?

To the Origins Centre. It is an incredible place.

You spoke of creating a space at the Biennale in which visitors would enter as if they were initiates. Please explain this reference.

This is because we are creating a space like the Wonderwerk Cave in Kuruman, which is a ritual space that uses blackness to enhance the experience for initiates. We would like to simulate a similar experience. The drawings I’ll be doing will be like rock art, so the pavilion in Venice will be a “cave”, and the visitors will experience an African space of initiation in the cave.

How can we start to think of land differently?

I think in architecture it is through representing it differently in drawings, as opposed to just a map. It’s like the difference between an anatomical diagram of your friend, versus a fond photograph of your friend. The one is cold, dead and impersonal; the other is full of meaning, emotion and memory.

You talked about the concept of “aspiration” and that in Kuruman, many people aspired to move from a matchbox house to a Tuscan-inspired home. What’s your response to this?

I don’t see anything wrong with aspiration, it’s just a pity that people are not aware of the fact that there is so much more out there to aspire to, Tuscan is just one option, and if a person likes that then OK, but I think we should put forward more options in case a person has other inclinations. I guess this is linked to my comment about diversity and variety.

One Joburg building you would like to own?

I can’t think of any really.

To see the work going into the South African Pavilion at Venice, you can follow the journey online. While there is talk of it being displayed in South Africa post-Biennale, this has not been finalised. The representation of South African architects and those from other African countries at this year's exhibition is historic in its diversity and its display of the wealth of talent. Among the leading architectural thinkers are Summayya Vally, Kate Otten Architects, MMA Design Studio, Wolff Architects – Heinrich and Ilze Wolff and Thireshen Govender.

Comments