No doubt you've heard the term 'partitions' thrown around in conversations about Polish history, but 'What were the Polish Partitions?' Oh dear, you really had to ask, didn't you? Explaining the Arab-Israeli conflict is probably an easier task!

To be honest, it's quite easy to explain what the Partitions themselves were. It's answering the 'Why?' that involves a lot more explanation. We'll try and make it as clear as we can for you:

The Polish Partitions were a series of three territorial seizures of Polish-Lithuanian land between 1772 and 1795 by neighbouring powers - The Kingdom of Austria, The Kingdom of Prussia and The Russian Empire. While the Poles famously resisted every time, their territory gradually became smaller and smaller. Eventually, in 1795, Poland would be completely wiped off the map and wouldn't exist as a country at all for about 123 years! We'll talk about what happened afterwards, later on....

The history behind the Partitions is a reflection of the geopolitical power dynamics that have existed from the early Middle Ages right up to current times. Poland has literally been in the middle of European power politics since becoming a self-declared sovereign state. The influence of its various neighbours and the fluctuations of its borders have contributed to the country's regional cultural nuances. It also continues to fuel the political ideology of many Polish nationalists who view Poland in an endless struggle for independence.

The Long & Complex History of Polish Borders

Like many other nations in Europe, the borders of Europe have changed more times than Michael Jackson's facial structure. But few nation-states have been as dynamic in their border fluctuations as the lands known as 'Polenia' or 'Polska' (for the sake of this article, we'll refer to it as 'Poland').

Why has this been the case? Well, geographically-speaking, Poland is the approximate centre of Europe. With the exception of the mountainous south, its lands are wide-open and flat. It's this geographical characteristic that has long been attributed to the etymology of the country's name - 'Polen' (ENG: field).

Being a flat, open country stuck in the middle of major European powers has often meant armies have been able to quickly roll across it and easily take what they please.

As for borders, it all started around 960CE when Duke Mieszko I founded the first independent Polish state, the Duchy of Poland, converted to Christianity and began christening the lands that lay under the jurisdiction of his union of West-Slavic tribes; in fact, Mieszko's official baptism in 966CE is considered the symbolic birth of what we consider the Polish state today. Over the following three decades, Mieszko and his descendants would quickly expand their territories towards the Baltic coast and further south. However, the Baltic coast proved a bit of a challenge, especially in christianising the fiercly-resistant pagan tribes that lived there.

They expanded into Danzig (Gdańsk) and its surrounding area in 1308.

Elsewhere, the relatively-young European power would squirm between the Ruś (now Ukraine, Belarus and Russia) to the east and Hungary to the south, while being occasionally interrupted by some unexpected guests, most notably the Mongol invasion in 1240 and the Galicians briefly forcing their way through in 1259. As the situation with the Teutonic Order became unbearable in the north, Poland made its historic alliance with Lithuania in 1386 and eventually stopped the expansion of the Teutonic Knights by defeating them at the Battle Of Grunwald in 1410.

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth & the Dominance of Central Europe

When the Polish-Lithuanian Union was officialised as a Commonwealth in 1569, it was one of the largest political powers in Europe and indeed a force to be reckoned with. At one point, it stretched from the Baltic to as far south as the Black Sea. Even in its final pre-partition form, it covered most of modern-day Poland, Belarus, Ukraine, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia! They were stars of the continental map in 1683, when they decisively fought back the Ottoman-Turks at the Battle of Vienna in 1683, halting the so-called 'Islamic Invasion' of Christian Europe.But the glory years of the Commonwealth were numbered, as it continued to be weakened by numerous conflicts. The Commonwealth waged war with Russia between 1654–1667 and were also invaded by Sweden in the early 18th-century during what is now known as the 'Deluge'. Call it jealousy or just pure belligerency, it seemed like no one really liked the idea of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. It was clear that the only way to deal with this mighty power was for the surrounding nations to have some kind of joint strategy to force the Commonwealth into submission.

Furthermore, since 1573 the Commonwealth had adopted a system of Elective Monarchy, which allowed the representative nobility (PL: szlachta) to elect their king or queen (the first was a French guy who lasted 5 years and fled the country never to return!). While this sounds quite democratic, the Polish-Lithuanian nobility were subject to bribery and this is how the Saxon monarch Augustus II the Strong got on the throne in 1697 (Russia and Austria had something to do with that!). Augustus II aimed to centralise royal power, and in the process of doing so, he ordered 25,000 Saxon troops within the Commonwealth's borders. Such a move caused outrage amongst the Szlachta and the Commonwealth was on the brink of Civil War. Using this turmoil as an excuse, Russian military entered the country and Tsar Peter the Great posed as a mediator in the infamous 'Silent Sejm' of 1717. While Augustus II was ousted as monarch, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was now effectively a vassal state of Russia.

First Partition of Poland

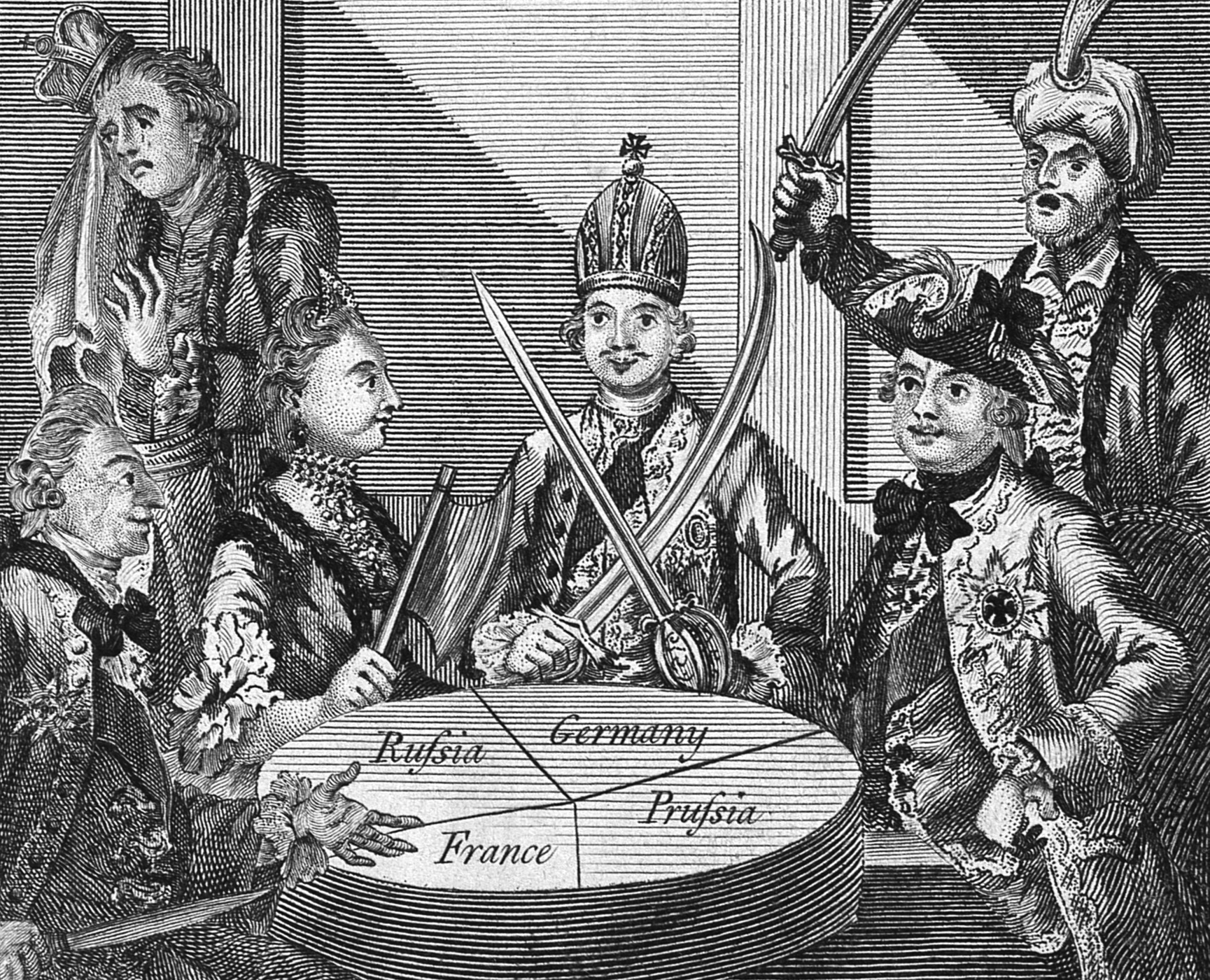

In the grand irony of history, the decline of the old enemy of Poland, the Germanic Teutonic Order, had since become the foundation of another rival power in Europe - the Kingdom of Prussia. It was their monarch, Frederick the Great, that engineered the first land grab of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. As relations between Austria and Russia became heated, Frederik proposed territorial seizures from the Commonwealth by each neighbour in order to 'restore the regional balance of power in Central Europe' This was agreed on August 5, 1772.

Second Partition of Poland

Over the proceeding 20 years, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth had been pushing for political reforms, in particular the establishment of a governing model similar to a Constitutional Monarchy. This was famously adopted as their Constitution on 3rd May 1791. From this point onwards, the country became The Commonwealth of Poland. Of course, the neighbouring powers reacted with hostility towards the reforms and the Polish-Russian War broke out in 1792. Commonwealth forces were ultimately no match for the superior Russian forces, though resistance in the southern theatre under the command of now-revered Pole Tadeusz Kościuszko and Prince Józef Poniatowski kept the enemy back for a longer period. The 'Second Partition of Poland' on January 21, 1793 was set in motion, after King Stanisław Poniatkowski opted for a cease-fire. Russia and Prussia annexed more territory on either side of the Commonwealth, whilst Austria did not participate in this round. Outraged by the King’s capitulation, Kościuszko – who hadn’t lost a single battle of the short-lived campaign – and the other notable commanders and politicians still faithful to the cause, emigrated to Leipzig to plot an uprising against Russian rule in Poland.

The 'Kościuszko Uprising' & the Third/Final Partition

In the aftermath of the Second Partition of Poland, those constituencies of the population which had opposed the reforms of the May Constitution had lost all credibility and Kościuszko saw the prospect of orchestrating a successful national uprising as less than impossible and more than necessary. He announced the Uprising on Kraków’s market square on March 24th, 1794. Assuming the powers of commander-in-chief of all Polish forces, he issued an act of mobilisation requiring at least one able-bodied male from every five houses in Małopolska to join his army, equipping themselves with an axe, pike, scythe or carbine. Large units armed only with farming tools were quickly formed. Once again, Kościuszko proved himself to be a superb military commander, winning a key victory at Racławice. News of Kościuszko's success inspired insurrections across the Commonwealth, however, Polish forces were too weak to continue their campaign against Russia, Prussia and Austria.In the third and final partition of Poland, between its three neighbouring powers, Poland was completely erased from the world map. It would be another 123 years before a Polish state would exist again!

Back from the Dead - The Second Republic of Poland

If you think that's the end of the story, think again!There were another 3 uprisings between 1795 and 1918 where Poles living in the partitions continued trying to overthrow their occupiers. Most notably the November Uprising of 1830 in the Russian partition prompted Tsar Nicholas I to remove any existing self-autonomy that remained there. Unfortunately, these moments of organised resistance ended in failure, though amazingly, even after their country had ceased to exist for over a century and a half, the Polish identity and the idea of a Polish state still remained. They just had to wait for some external factors to loosen the grip of their occupiers. And it came in 1918...

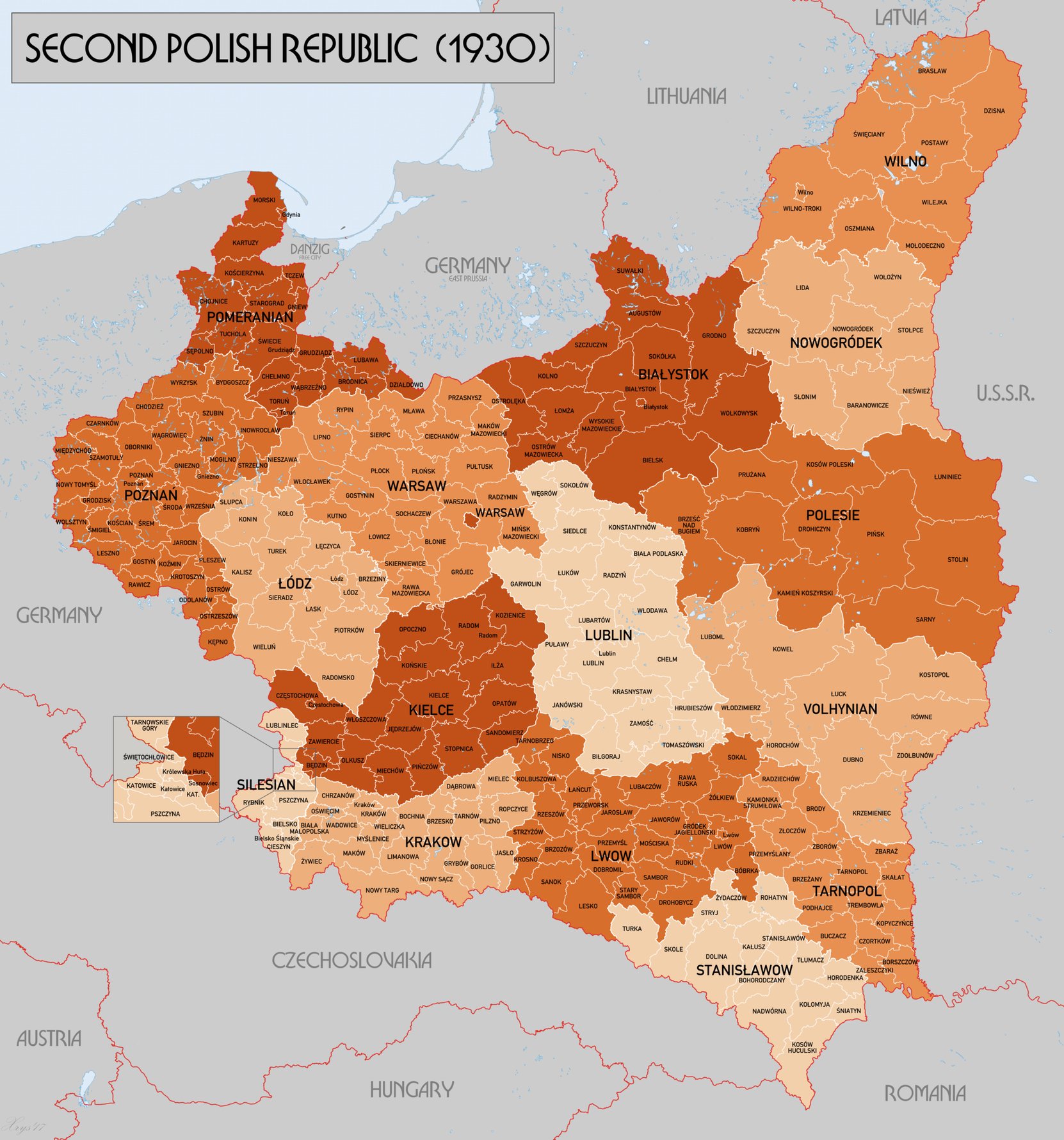

Following the end of World War I,

Following Russia's withdrawal, Poland was able to consolidate more of the former Polish-Lithuanian lands to the east.

The League of Nations turned Danzig into the semi-Autonomous 'Free City State' that was separate from both Germany and Poland. The complex political and economic arrangements motivated Poland to push for access to the Baltic Sea (see our article on 'The Polish Corridor'), as well as the development of its own port in Gdynia.

Legacy of the Polish Partitions

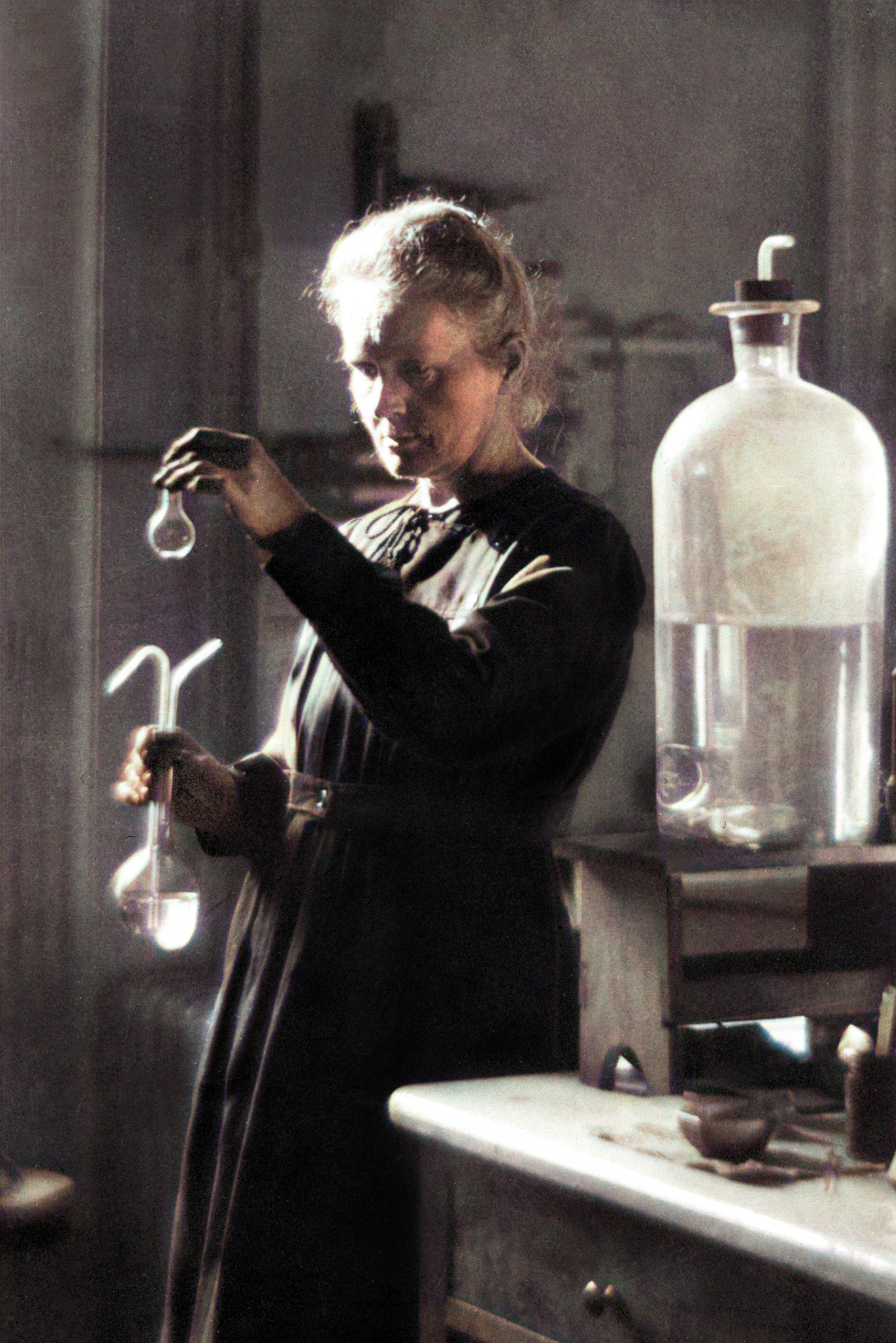

Life in the partitions, particularly in the Russian- and Prussian-occupied areas, was a period of Polish cultural repression and economic hardship, and many Poles involved in the uprisings of the period were either imprisoned, ruined financially or forced into exile. This was the start of a huge exodus, which is now referred to as 'The Great Emigration'. In this period, some of the most notable historic Poles moved abroad, mainly to France, to fulfil their life achievements.For more, see our article: Big In Paris: The Great Emigration from Poland to France.

The old divisions that existed between 1795 and 1918 had varying effects on Poland's development. Cities like Bydgoszcz (formerly Bromberg), Wrocław (Breslau) and Poznań (Posen) were heavily developed and invested-in during their periods under Prussian rule. Linguistically, the voivodeships of Wielkopolska and Pomerania have a higher number of Germanic words in their regional dialectics, as well as using 'Polish' Germanisms - German expressions that have been translated literally into Polish.

showing a dying freedom fighter scrawling 'Jeszcze Polska nie

zginęła' (ENG: Poland is not yet lost) with his own blood.

When Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia invaded Poland in September 1939, many Poles were plunged into an existential crisis, seeing the invasion as a return of the 123-year partitions. A high number of suicides during the period are attributed to people not willing to accept what they saw as 'history repeating itself'. Amongst these numbers, was Polish author/artist Stanisław 'Wiktacy' Witkiewicz.

In the 21st Century, it's been noted that the political division of Poland between a more progressive 'A' region in the west and the more conservative 'B' region in the east is correlated with the old partition borders. This is usually attributed to the west (Poland A) having experienced much higher development rates under Prussia, compared to the eastern half (Poland B) which had been severely neglected economically and socially by the Russians and the Austrians.

Comments