Befitting the city that informally bears his name, Plečnik was born in Ljubjana on the 23rd of January in 1872, the fourth child of carpenter Andrej Plečnik and his wife Helena. As with most kiddywinkles in the 19th century, the assumption was the little Jože would follow in daddy’s footsteps. Little Jože had other ideas though. As his studies progressed, he secured himself a spot at the school of Industry and Crafts in Graz, hometown of Arnold Schwarzenegger. From here our Plečnik moved to the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna.

In Vienna Jože kind of half followed in his father’s footsteps as he found himself designing furniture. This wasn’t the most intense of jobs though, so he found himself spending a lot of time visiting galleries, museums and exhibitions. It was at one of these exhibitions that he saw Otto Wagner’s plans for a cathedral in Berlin. This is often referred to as a turning point for Mr Plečnik. Just a few years later, Plečnik would find himself under the teachings of Wagner (1894-97).

As we’ll see, Plečnik’s professional life is divided into three periods, and Vienna represents the first of these. His work on the Zacherl House in 1905 was something of a coming out party for the Slovene, when he established himself as one of the finest young architects on the continent. The second period was about to begin.

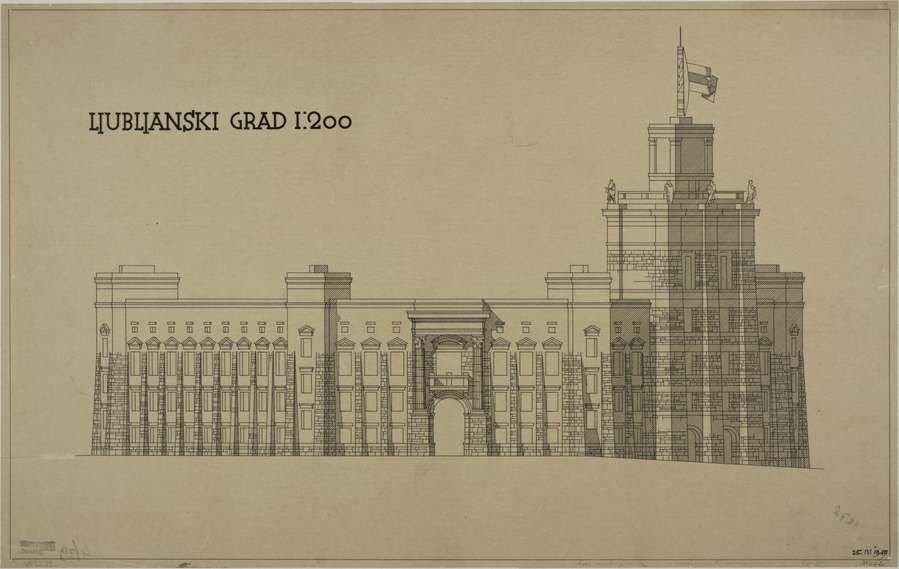

Between 1911 and 1920 Plečnik found himself in Prague, the capital of what was then Czechoslovakia. Well, it became Czechoslovakia after World War One, and the new nation-state needed a powerful symbol. Plečnik was entrusted with creating this, and was put to work on Prague Castle as the Castle Architect. This was the biggest undertaking of his professional life and took some 15 years to complete. He also worked on the Church of Sacred Heart in the city, and was a professor at the art school. His heart yearned for his hometown however, and this yearning was too strong. 1920 saw him head home to Ljubljana, and it is here that his greatest achievement would come to fruition.

There aren’t many cities in the world that have the architectural feeling that Ljubljana does, and fewer still that came from the creative juices of a single person. From 1920 until his death, Jože Plečnik reimagined Ljubljana and created the sweet, delightful aesthetic joy that we know and love today. Plečnik loved his hometown, and this love is clear to all who stroll around the sleepy streets of the Slovene capital.

Even to the untrained eye the variety of the work is astounding. Tromostvoje (or Triple Bridge) is the centrepiece of it all, a three pronged bridge in the very centre of town over the Ljubljanica River. It is a piece of work that thousands traverse every single day, that is photographed from all sorts of angles and never looks less than impressive. Continuing the bridge theme we have Cobbler’s Bridge (Šuštarski most) a little further down the river, another graceful spot for a Ljubljana stroll.

There are two pieces that take the Plečnik Ljubljana cake for our money though. Cemeteries aren’t usually considered must-see spots in a city, but Ljubljana’s Žale cemetery is must-see and then some. This is because of the Plečnik designed entrance gate, a monolithic structure that is as imposing as it is poignant. This grand arched structure is made of stark white collonades, and is supposed to represent the gateway between the lands of the living and the dead. Very spiritual we’re sure you’ll agree, and when standing below the archway it is difficult to disagree with its supposed function.

Then there is the stunning outdoor theatre in the city centre called Križanke. This translates as ‘crossword’, but don’t expect blank white boxes and a list of cryptic clues upon arrival. This open-air theatre was Plečnik’s last major contribution to the city, and what a way to go out. It frequently plays host to many summer events, and if there is a type of music that isn’t made better by taking place in a gorgeous outdoor theatre we have no interest in hearing it.

As World War Two closed its doors and Slovenia was re-incorporated into Yugoslavia, Plečnik found himself slowly phased out of the architectural world. His work was still appreciated, but he was considered old-fashioned and out-dated. Still, he garnered a high level of respect from the Socialist regime that stood him in good stead. Križanke was completed in 1956, and a year later Jože Plečnik passed away in the city he had truly made his own. Fittingly, he received a state funeral at Žale.

Jože Plečnik’s legacy is arguably untouchable when it comes to Slovenians. His work in Prague and Vienna is still fawned over today, and his influence as one of the founders of modern European architecture isn’t up for debate. His work was high in quality and completely original. Many restaurants in Europe today are obsessed with the idea of being ‘traditional yet modern’, but Plečnik managed this in his architecture almost effortlessly. He expressed ideas without losing functionality. He understood that besides being the buildings and structures that join together our day-to-day life, architecture had (and has) a responsibility to inspire and inform through monumentality and beauty.

A 1986 retrospective travelled the world as interest in Plečnik began to reappear. Among other places it was shown in Milan, New York, Munich and Madrid, as Jože Plečnik became the first Slovenian artist to make an impact in the USA. Friedrich Achleitner, the Austrian poet, referred to Plečnik as an ‘architectural fundamentalist but also an artisan’. Plečnik’s influence on his hometown is unrivalled. Not bad going for the son of a cabinet maker.

Comments