Stanisław, originally intended for Wawel Cathedral.

The first patron saint of Poland, and also the official patron saint of the city of Kraków, St. Stanisław (St. Stanislaus) is almost ubiquitous in Polish communities, his image seen in numerous stained glass windows and paintings, and his name gracing not only Polish churches at home and abroad, but also once a popular name for children (how many Stans, Stasieks and Stasias do you know?). It is St. Stanisław's sarcophagus in Wawel Cathedral before which Polish kings kneeled upon coronation, and where generations of Poles have prayed ever since. Canonised in 1253 by Pope Innocent IV, few Polish figures have been more adored, but surprisingly little is actually known about Stanisław. In fact, there's debate not only about when he was born and when he died, but even whether he was a good man in the first place. A deep dive into the vague life and venerated legacy of this Cracovian bishop who challenged a king and became a martyr reveals that his saintly status today may be built purely upon centuries of superstitious belief that his death placed a curse upon the nation that reveres him.

Stan from Szczepan

Not to be confused with the 16th century St. Stanisław Kostka, the St. Stanisław of our present concern - and the namesake of most subsequent Stainsławs - was known as 'Stanisław Szczepanowski,' or 'Stanisław of Szczepanów' - after the Małopolska village 52km east of Kraków where he was born in 1030. Of his early years we know only that he studied in Gniezno (then the capital of Poland) and then abroad somewhere, returning to be ordained a priest in Kraków, where he gained fame as a preacher and was slowly groomed to be the successor to the Bishop of Kraków. This he achieved upon the Bishop's death in 1072, gaining significant political influence as one of the first native Polish bishops in the country.

Though touted as one of the most magnificent clerical careers of the Piast era, Stanisław's stint as Bishop of Kraków was literally short-lived and details are few. His successes include bringing papal legates (personal representatives of the Pope) to Poland, establishing numerous Benedictine monasteries in PL with King Bolesław II, and reestablishing the Gniezno metropolitan see - a prerequisite for Duke Bolesław's coronation as King, which took place in 1076. Most often referred to in history books as King Bolesław II the Bold, Poland's third ruler was also known in turns as Bolesław ‘the Generous’ and ‘the Cruel,’ the latter due in no small part to his leading role in Stanisław's grisly death.

Deeds of the Dead

Stanisław's power and influence was primarily built on superstition and soon lead to direct conflict with the monarch he helped ascend the throne. The first dispute was over a piece of land which Stanisław claimed to have purchased from a fellow named Piotr before he died. The family disputed that claim, claiming Piotr's land should still be in their family, and they brought the issue before the King, who ruled in their favour.

Stanisław was not pleased and there was only one thing to do. In a spectacularly self-serving display of supernatural power, the Bishop went to the cemetery, dug up the three-years-dormant remains of Piotr, and in front of a company of witnesses, bade the mouldy corpse to rise, which it dutifully did. Stanislaw then dragged his reanimated witness before the dumbfounded royal court where Piotr berated his kin and confirmed that he had indeed sold his land to the Bishop. Thanked for his participation and asked whether he would care to continue living, Piotr apparently declined and was relaid to rest until needed for an appeal. The King, clearly intimidated by Stanisław's dangerous otherworldly powers, made no such appeal necessary, throwing out the case and conceding the land to his spooky Bishop.

'Murder in the Cathedral'

The origins of the second, more serious feud between the Bishop and King Bolesław II are a bit murkier. One version relates that Bishop Stan was outraged over the King's harsh treatment of unfaithful wives whose husbands were off at war in Ruthenia, while another has Stanisław outspokenly criticising the King’s own sexual promiscuity. The only contemporary source, 'Gallus Anonymus,' rather tiptoes around the cause of the break between the Bishop and Bolesław in his famous Chronicles, but carefully condemns both sides - the 'traitorous Bishop' and the 'violent King.'

Whatever the case, in 1079 Stanisław brashly excommunicated the King, essentially banishing Bolesław from the sphere of the Church. Quite a flex on Stan's part, this not only outraged the King, but bolstered his political opponents; in fact, more recent theories have suggested Stanisław was directly involved in an opposition movement intent on overthrowing the King. Needless to say, the Bishop was living dangerously, and, of the two of them, the one perhaps more deserving of the title 'the Bold.'

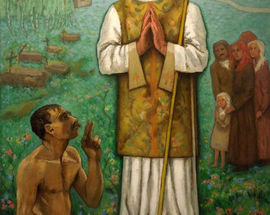

Trying to exert authority over a king is never wise, however, and in response, the enraged King accused Stanisław of treason and ordered his assassination. Finding no volunteers or even obeying courtiers for the task of executing a fearless, mystical man of God possessed of unearthly powers, the King rather 'boldly' took the task upon himself. Bishop Stanisław was celebrating mass at the Church at Skałka, just outside Kraków (today in Kazimierz district) when the King struck him down with his sword, splattering blood upon the altar. According to legend, Stanisław was then dismembered for good measure and his assorted pieces were thrown into the pool in front of the Skałka Church. Saving the theatrics until the raging tyrant and his men had dispersed, four eagles soon appeared to stand watch over the process as Stanisław's mutilated parts then proceeded to miraculously reassemble themselves, but surprisingly stopped short of reanimation; presumably Stan thought he could accomplish more as a martyr. And he did, posthumously winning his spat with the King when outrage over his death lead directly to Bolesław’s dethronement and banishment.

Bolesław the Banished, Bolesław the Obscure

Despite living up to his 'bold' nickname, the backlash against the King for executing Bishop Stanisław was strong and swift. The opposition movement that had already spread amongst Poland's barons now intensified and led to open revolt, forcing Bolesław from the throne, where he was replaced by his brother, Władysław I Herman. Undone by his pride, Bolesław was forced to flee the country and it's unknown what exactly became of him, or even where he was buried - quite unusual in the case of a king.

According to some accounts, he naturally fled to neighbouring Hungary, which was under the rule of Władysław I Święty (King Ladislaus I), who Bolesław himself had installed as monarch after driving the former King Solomon out with his military. Legend says that Bolesław's abhorrent behaviour in the court of King Władysław, however, soon lead to his poisoning by an unknown assassin in 1081 or 1082 at the age of about 40.

Another version, meanwhile, contends that Bolesław fled to Rome to beg Pope Gregory of forgiveness for his transgressions against the Church and for murdering the popular Bishop. The Pope granted no mercy, instead condemning Bolesław to wander the land as an anonymous mute repentant. Some believe he was received at the Benedictine Abbey in Ossiach (in present-day Austria), where he lived in obscurity, only confessing his true identity upon his deathbed in old age. Despite a tomb at the Ossiach Abbey which bears the Latin inscription 'REX BOLESLAVS OCCISOR SANCTI STANISLAI EPISCOPI CRACOVIENSIS' (Boleslav, King of Poland, Murderer of Saint Stanislav, Bishop of Cracow), many historians are sceptical of this account, as it only appeared from a Polish historian in the late 15th century. The tomb has been exhumed twice in modern times, and inside were discovered the 11th century remains of a male, alongside the armour of a Polish knight, but no definitive conclusions as to its veracity have been drawn. Despite this, the Abbey has become a pilgrimage site for Poles interested in the fate of Poland's third monarch.

Yet another story says that Bolesław's remains are actually at the Benedictine Abbey in Tyniec (just outside Kraków), which he may or may have established (the jury's out on that as well).

Martyrs Make the Best Saints

While King Bolesław managed to fall into obscurity within his own lifetime, the cult of Stanisław began to grow immediately upon his death, despite the uncertainty of most historians over whether to regard the bishop as a hero or traitor. Aside from his gruesome post-mortem magic trick and the suspect resurrection tale of Piotr, Stanisław had no other claims to sainthood as far as mystic visions, healing powers, or gory stigmata are concerned. What precipitated his canonisation process was actually an analogous case occurring in England, where Thomas Becket was granted the status of martyr-saint. Becket was the Archbishop of Canterbury, murdered in 1170 by followers of King Henry II due to going excommunication-happy on Church members who exceeded their privileges and pissing off the monarch - something that rang a bell with Stan’s followers.Patron Saint of Superstition

(until recently, photos were forbidden).

In 1245, Stanisław's remains were moved to Wawel Cathedral, which became Poland's principal national shrine, and by 1253 he had been canonised as a martyr-saint. Beginning with King Władysław I Łokietek - who reigned from 1320 to 1333 and succeeded in reunifying the Polish kingdom - all of Poland's kings were crowned while kneeling before Stanisław's sarcophagus at the centre of Wawel Cathedral. Not bad for a reckless bishop who could just as easily have been considered a national bogeyman.

In Kraków

Since 1254 to the present day, yearly processions led by the Bishop of Kraków set out from Wawel Cathedral to the Skałka Church in Kazimierz on the first Sunday after May 8th - the day of Stanisław's assassination (though in the 1960s the Church moved his feast day to April 11). In addition to Stanisław's sarcophagus and relics in Wawel, at Skałka visitors can see an altar dedicated to St. Stanisław in the place where he was murdered, which includes a piece of the blood-stained stump upon which he is said to have been quartered. The pool where his dismembered body was dumped is today adorned with four eagles and a 17th century sculpture of the Bishop, and includes a fountain from which foul-smelling water - famed for its healing powers - bubbles forth. A four-metre monument of St. Stanisław is also included alongside Kraków's other saints in the grounds behind the church.

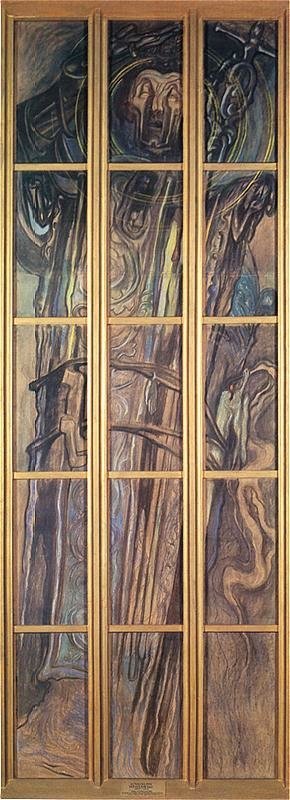

Lastly, head to Plac Wszystkych Świętych (All Saints' Square) to see a massive stained glass window depicting St. Stanisław, as rendered by Kraków's famous artist (and fellow Stanisław) Wyspiański - part of the modern Wyspiański Pavilion.

_m.jpg)

Comments