Reakcja Pogańska (1030s)

Poland is indeed one of the most religiously-devout countries in the world, with 93% of its citizens considering themselves Roman Catholic. But when Christianity was introduced to this area of Central Europe in 966, an event which is generally accepted as the foundation of Poland as a country, things did not go so smoothly. Duke Mieszko I, Poland's first leader, warred with pagan Baltic tribes on his northern borders as he tried to consolidate his territory, a conflict that would last until the late 13th century. But it was a series of internal uprisings of the peasant class in the 1030s that threatened to completely destabilise the new nation. This period, known as Reakcja Pogańska (ENG: The Pagan Reaction) saw churches and monasteries burned down and many of their resident priests and monks murdered in a revolt against the system. Historians debate whether the motives were religious (Christianity was the religion of the wealthy, ruling class) or economic, since the church had introduced high taxes in the kingdom. The destruction in old nation's heart of Wielkopolska (ENG: Greater Poland) was so bad that the capital in Gniezno was moved to Kraków!The statues being liquidated in this image look distinctly Greco-Roman and are, therefore, inaccurate!

The Kosciuszko Uprising (1794)

When it comes to Polish glory days, there weren't any heights higher than The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth - one of the largest countries of 16th & 17th century Europe, but falling into decline by the 18th and gradually carved up by its more powerful neighbours beginning in 1772. Attempting to strengthen itself through reform, the Commonwealth passed the May Constitution of 1791, but only provoked Russian invasion, eventually leading to the '2nd Partition of Poland.' By 1793 the Polish Commonwealth was only a weak buffer state between Prussia and Russia, one-third its original size, with a puppet king and no independent army.

Enter Tadeusz Kościuszko, who had served in and been inspired by the American Revolution, and believed inciting a national uprising was his patriotic duty. Despite desperate odds, Kościuszko announced his uprising on Kraków’s market square on March 24th, 1794, wherein he became commander-in-chief of all Polish forces, and issued an act requiring at least one male from every five houses in Małopolska to join his army; the result was large units of peasants armed only with scythes. Catherine the Great ordered Russian forces to crush the rebellion, and the two sides collided near the village of Racławice, where Kościuszko’s ragtag army actually won the day. Inspired by Kościuszko’s victory, peasant insurrections broke out across the Commonwealth, but Polish defeats began to accumulate quickly once Prussia entered the war in alliance with Russia. Kościuszko was defeated, injured and captured at the Battle of Maciejowice on October 10th, where his army was outnumbered four to one; new commander Tomasz Wawrzecki was forced to surrender on November 5th, shortly after the Russian capture of Warsaw. With the flames of revolution extinguished, the 'Third Partition of Poland' (October 24th, 1795) transpired, dividing its remaining lands between Austria, Prussia and Russia, and erasing Poland from the jigsaw of Europe for the next 123 years.

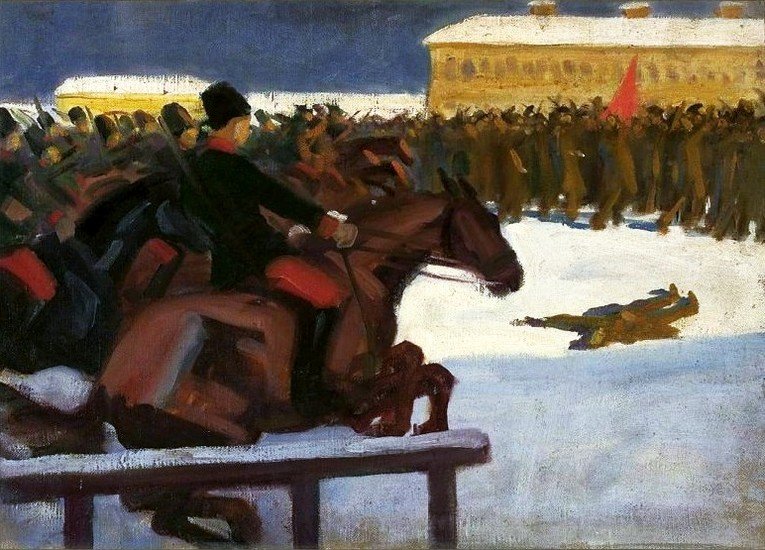

November Uprising (1830-31)

Also known as the Polish–Russian War of 1830–31 or the Cadet Revolution, this was an armed rebellion in the heartland of partitioned Poland against the Russian Empire. It began on 29 November 1830 in Warsaw when the young Polish officers of the local Army of the Congress Poland's military academy revolted, led by lieutenant Piotr Wysocki. Despite local successes, often seen as pyrrhic victories, Polish efforts could not halt the overall progress of the numerically superior Russian Army. The aftermath of the uprising led Tsar Nicholas I to decree that Poland was to be an integral part of Russia, with Warsaw little more than a military garrison. In another universe, the November Uprising may have succeeded if it was better organised - overall, the Polish side largely consisted of a regular army (70,000 troops, 30% were fresh cadets), and not a band of civilians forced to fight for their country.

January Uprising (1863-64)

Just 32 years after the failed November Uprising, another national uprising would grip the territories of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Although the January Uprising of 1863-64 would ultimately go down as another failed attempt to overthrow Russian rule, (Polish fighters mainly included poorly armed peasantry fighting against numerically superior, and better equipped, regular Tsarist troops), the uprising itself was much larger in scale, and would last longer than all previous insurrections during the 123 years of partition. This time, what's more, the impact on Polish society and the Polish psyche would prove great and impact events in Poland well into the 20th century...

1905 Łódź Revolution

Bet you've never heard about this before?! You may be as surprised as we were when we first learned of Łódź's own attempt at revolution. But that's what you get when you mix a working class culture with a hatred for Imperial Russia. So it proved in 1905, when the people of Łódź rose in rebellion against their Tsarist rulers. Russia’s disastrous military campaign against Japan in the Russo-Japanese War (won handily by Japan) had far-reaching consequences, battering an already fragile economy. Over 100,000 workers in occupied Poland found themselves laid off, and nowhere felt the pinch more than the factory city of Łódź. A wave of popular unrest spread across the entire Russian Empire (known as the 'Russian Revolution of 1905'), with relations between the authorities and the working class reaching a nadir when an estimated 1000 unarmed demonstrators in St. Petersburg were killed or injured on January 22nd, after being fired upon by Tsarist troops (the incident came to be known as 'Bloody Sunday'). By then workers in Łódź were already on strike, and over 400,000 workers had laid down their tools across the country, paralysing the economy and panicking the Russian authorities as the discontent evolved into street protests and a brutal Tsarist response...

Wielkopolska Uprising (1918-19)

World War One shook a lot of things up in Europe, seeing the creation of many new sovereign states. By the end of the horrific conflict, Poland had technically already gained independence centrally in Warsaw but many historically-Polish areas were still under German control. Since post-WWI Germany was in shambles, the time was right for Poles in regions where they had ethnic majorities to rise up and fight for inclusion in the new Polish state. This occurred in multiple areas, but most notably in Wielkopolska (ENG: Greater Poland), where Poznań (then the German city of 'Posen') was located. In December 1918, moments after a stirring patriotic speech was given by the celebrity pianist Ignacy Jan Paderewski to a crowd in the Poznań's centre, shots began firing and Polish forces seized the train station within hours. The momentum drew support from the surrounding area and the fight against the German military in the region lasted for 3 months. Ultimately, the French intervened to broker a new armistice, but by this stage the already-exhausted German forces had little if any control left in Wielkopolska. By 1921, Poznań and most of the region had joined the 2nd Polish Republic!

Silesian Uprisings (1919-21)

After Wielkopolska, another post-WWI uprising followed in Upper Silesia - a historically-contentious, ethnically-mixed, resource-rich area between Poland and Germany. The messy Treaty of Versailles originally intended to incorporate most of these lands into the new Polish Republic. However, loud protests from Germany - which claimed it would be unable to pay its war reparations and might even succumb to famine - convinced the Allies to settle the matter by democratic vote...in two years’ time. In the meantime, the existing German administration and police would be left in place.Inspired by the rhetoric of Wojciech Korfanty, armed Polish insurrectionists began seizing control of Silesian towns and engaging the German Army in guerilla warfare in August 1919. This 1st spontaneous uprising was quickly squashed, but exactly one year later, a 2nd more organised Polish uprising achieved great success until Allied military involvement secured a ceasefire by granting Poles equal representation in local government.

Warsaw Ghetto Uprising (1943)

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising of 1943 has gone down in history as an act of defiance, an act of protest against the inaction of the world in helping the Jewish people in their plight during the Second World War. This was their time to fight. And so it was to be that from 19 April to 16 May 1943, following years of torment, the fighters of the Warsaw Ghetto rose up, vastly outmatched by the superior numbers and weaponry of the German war machine. But that wasn't the point. There was never any real hope of winning. The fighters had a simple choice: go quietly and die anyway, facing extermination in a camp; or go fighting, defying the barbaric system which had spread across Europe. They fought, and almost all the Jewish fighters perished.

Warsaw Uprising (1944)

The 2nd wartime uprising in Warsaw would result in 200,000 civilian and insurgent deaths, and near destruction of the city. August 1, 1944: Warsaw, subject to five years of fascist hegemony, rose up in popular rebellion in what would go on to be recorded as the largest ever uprising in the German occupied territories. With German morale in ribbons, a retreat from Warsaw in full swing, and the Red Army already on the east bank of the Wisła, no time seemed better than the present. Following close contact with the Polish government-in-exile, and assurances of Allied aid, the Home Army (Poland’s wartime military movement a.k.a the Armii Krajowy or AK) launched a military strike with the aim of liberating Warsaw and installing an independent government. During the event the Red Army made no concerted attempt to help the Poles, while promises of Allied support proved largely empty. As for the Nazi hierarchy, they reacted with blind rage to this stroke of Polish insolence, and what ensued was an epic 63 day struggle during which the Home Army faced the full wrath of Hitler. The most notorious chapter of Warsaw’s history was about to be written...

1956 Poznań Uprising

Poland had switched from Nazi to Soviet occupation in 1945 and the so-called Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa (ENG: Polish People's Republic) or PRL was formed as a communist state in 1947. The death of Stalin in 1953 provoked a certain degree of optimism among Poles, promising an end to the social and political terror associated with the Soviet Union’s hegemony of Central and Eastern Europe.

saying 'We demand bread!' before violence broke out.

The Nowa Huta Riots of 1960

Built beginning in 1949 on the outskirts of Kraków, Nowa Huta was conceived as a working-class socialist utopia. Atheist by design, it was this aspect that the new residents objected to, and they began fighting for a permit to erect a Catholic church right from the get-go. With the political thaw of October 1956, permission was suddenly granted, a site was chosen and soon a large wooden cross was consecrated in Nowa Huta’s Theatre district. In June 1958, however, work was promptly halted as the leniency of the communist authorities had apparently expired, and the site was reallocated for a school, inciting massive protests. When authorities attempted to remove the cross, the “revolution in Nowa Huta” began in earnest and the army had to be called in. Soon a dense column of military trucks, armoured cars, cannons and machine guns sealed Nowa Huta off from central Kraków. On April 27, 1960, tensions broke into an all-out street war that lasted for several days as water cannons, tear gas and dogs were unleashed on some 4000 ‘Defenders of the Cross.’ By the end, official reports listed military casualties at 200 and eyewitnesses suggest the civilian number would have been three or four times as much. Officially 493 people were arrested and 87 sentenced to prison stints from 6 months to 5 years in length. Although the ‘Nowa Huta Cross’ still stands today, locals would have to wait for a church until 1977, when Arka Pana (The Lord’s Ark) - which they funded and built entirely without government assistance - was finally consecrated nearby.

The Solidarity Revolution (1980s)

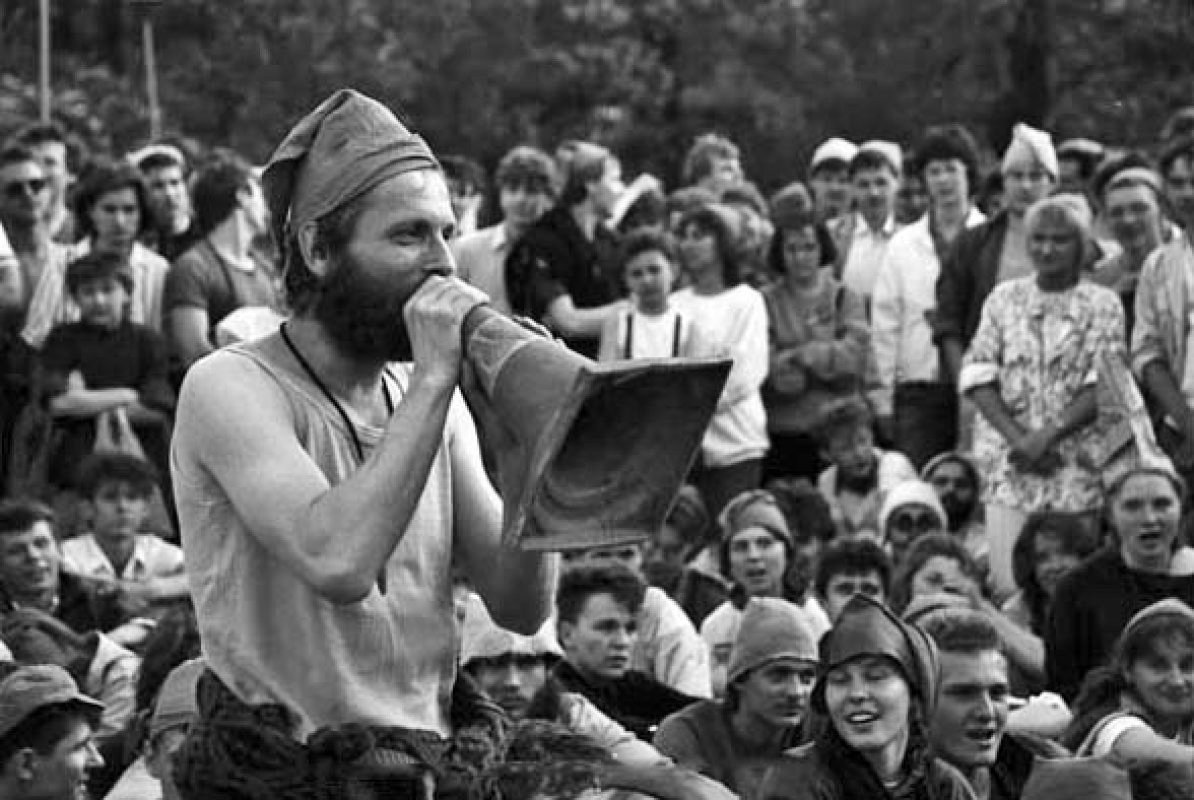

Arguably the most important uprising of all, not just because this David-and-Goliath face-off resulted in the end of Communism in Poland, but also because it adhered to the post-Gandhi philosophy of realising change through non-violence. The worsening living and working conditions during the Communist regime was itching at all ends of Polish society, but it was the shipyards in Gdańsk and Gdynia that first made their feelings known. In 1970, violent clashes between workers and authorities left 44 dead and, although it forced a leadership change in the administration, tensions never truly eased. They resurfaced again in August 1980, when the dismissal of female crane operator, Anna Walentynowicz, in Gdańsk’s Lenin Shipyards provided the spark for workers who were already prepared to go on strike due to pre-existing disillusionment. Thus, with Walentynowicz in mind, the Solidarity trade union was born and the strikers locked themselves in the shipyards, avoiding the bloodshed of 1970. Led by electrician Lech Wałęsa, a list of 21 demands were hammered out, known as the August Accords, which were finally agreed to by Communist Authorities on August 31 1980.

Wałęsa would go on to be Poland's first democratically-elected President in 1990. Source: Nationaal Archief (CC0 1.0)

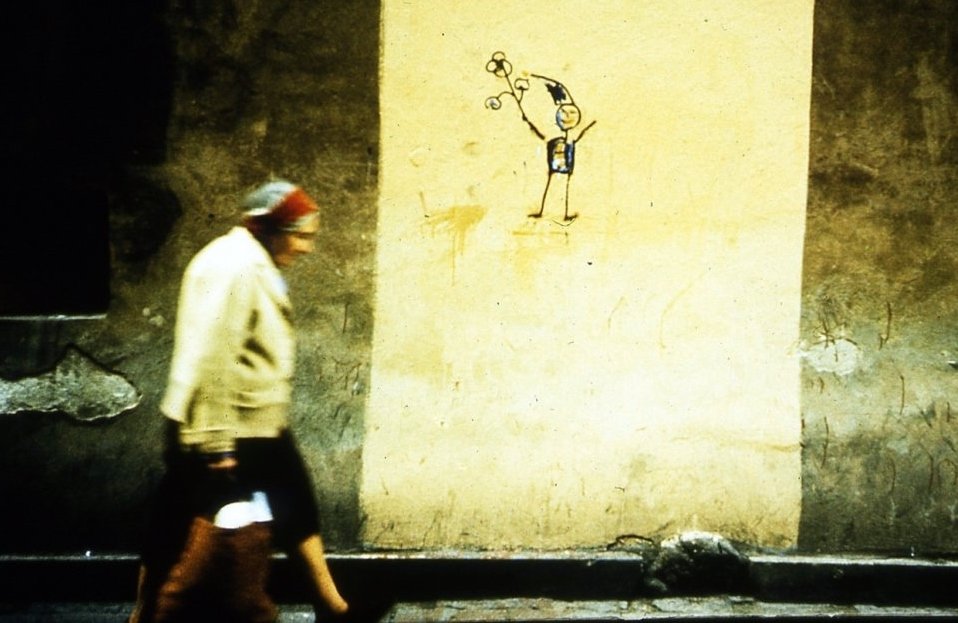

The 'Gnome Revolution' of the Orange Alternative (1980s)

While Solidarity rightly gets the lion’s share of the credit for toppling the communist system in Poland, Wrocław also developed its own underground protest movement, the role of which should not be understated. Known as the ‘Orange Alternative,’ Wrocław’s young activists used absurdity and nonsense to stage peaceful, yet subversive protests against the communist regime. Led by art student Waldemar ‘Major’ Fydrych, the group specifically ridiculed the establishment’s fruitless attempts to censor public space by subversively filling it with small, crudely-rendered gnomes. This simple device humiliated the authorities, who looked ridiculous and pathetic to the outside world as they painted over the innocuous drawings and arrested anyone caught making them.

As the movement gained popularity, gnomes began appearing on the walls of other Polish cities as well, and also in political demonstrations throughout the late '80s as Fydrych and his legions of followers donned peaked orange hats while staging massive happenings across PL that were so silly, the ensuing arrests seemed ludicrous. Perpetually in and out of prison while peacefully protesting for the rights of gnomes and other nonsensical causes, the Orange Alternative successfully brought the situation in Poland to international attention and played an important role in the fall of communism. Today gnomes have become a symbol of Wrocław, and you’ll find them all over the city as a tribute to the Orange Alternative.

Comments